A quick note for our faithful followers – we are moving the blog to a new location: crockerland.wordpress.com We have been very quiet in recent months as our attention has been on other projects, but with the exhibit opening in just over a year, the focus will be back on Crocker Land. We hope you will follow us to our new home.

Author Archives: Genevieve LeMoine

Guest Post II

Today we present another guest post, this one from museum intern Meg Bunke ’14. Meg began working at the museum this summer and together with Alex has delved deeply into the Ekblaw collection. Here she reflects on some of what she has gleaned from her work.

The Man Behind the Journals by Meg Bunke, ’14

In the time I have spent going through Elmer Ekblaw’s artifacts and reading his journals this summer, I have come to feel as if I know him personally. Many of his letters and items hold a happy connection for me because they refer to my hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, where Ekblaw lived and taught at Clark University for many years. His pair of nifty foldable glasses, made by opticians in Worcester, were small enough to take along on the expedition. Among his books was one checked out from the Worcester Public Library, which the museum curator recently returned to them––many years overdue!

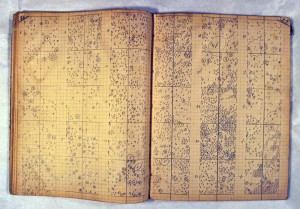

I appreciate Ekblaw’s meticulous records about the rocks, birds, plants, and geography of Ellesmere Island, not only for the information he collected but also for the candor and humor that comes through in his writing. Some of his scientific entries are aesthetically beautiful, like this schematic of the location of various plants, each marked by a number:

Pages from one of Ekblaw's notebooks showing the distribution of plant species in carefully measured squares.

His sometimes-playful writing demonstrates a childlike excitement in his Arctic experiences. Ekblaw revels in building his first cairn on a sledging expedition along Canon Fjord in April 1915. He proudly announces that it makes him feel “like a real explorer!”

His commentary about interactions with other crew members or with his dogs add humor to his journals, as in this excerpt from January 3rd, 1917:

“Knud Rasmussen and Neheteslasook slept in our tent this night, disturbing our domestic arrangement very much. There is no sleeping in the tent that K. R. occupies for he talks all the time.”

In another journal, he tells a sad story about an eider duck he observed while going for a walk along a fjord. The “young king eider had waddled from one iceberg pool to another in search of open water. When we found him he was so nearly fatigued that when we tried to catch him, he dived under the ice and was unable to get back and so drowned.”

The Crocker Land trip may have lasted much longer than Elmer Ekblaw expected, but his writing reveals sustained enthusiasm for his endeavors. His tales of everyday experiences in the Arctic are funny and touching, and his excitement over his first Arctic voyage is contagious.

Guest Post: Interning at the Arctic Museum

Previously we mentioned the recently donated collection of materials belonging to W. Elmer Ekblaw. Today we have a guest post from one of our interns, Alex Brown ’13, who has been working with the collection since September. This summer she is working at the museum as a Gibbons Intern helping us in the early stages of developing an interactive component of our Crocker Land exhibit. Here she describes some of the adventures she and Annie Streetman ’12 had last year while working with the Ekblaw collection.

Interning at the Arctic Museum, by Alex Brown, ‘13

In September of 2011 the grandchildren of W. Elmer Ekblaw donated a collection of material relating to the 1913 Crocker Land Expedition. The gift includes journals, papers, books, specimens, and an abundance of artifacts. For the last year, the museum has been studying and processing the collection in preparation for an exhibit planned for 2014. Annie Streetman ’12 and I spent many hours working on the collection during the 2011-12 academic year.

When we first encountered the Ekblaw collection it appeared to consist of boxes of stuff. Over the last year as we sorted and catalogued we came to know the collection intimately. Our journey began with preliminary inventory and the daily mystery of uncovering the true identity of objects. It felt like a real life game of pictionary.

For instance, the object resembling a pencil sharpener turned out to be a device for sharpening razor blades and knives. On the other side of the spectrum, some objects such as the forceps matched modern tools right there in the lab. Every artifact was meticulously examined, catalogued and labeled. Writing condition reports proved a challenge for some artifacts; for instance, how does one describe a box of rocks? (We went with “rocky!”)

We learned how to distinguish walrus ivory from narwhal ivory, and got into a long debate about whether the objects in a jar were polar bear claws or bird beaks (which look surprisingly similar in a old glass jar). A few hours later our curator, Genny, answered the question for us.

Elmer Ekblaw kept meticulous records of his time in the north. As the most productive scientist on the expedition, he studied geology, botany, ornithology, glaciology, and even anthropology. A combination of scientific and personal objects make up the collection. When going through it, some pieces almost make you feel as if you yourself are preparing for you own expedition north. Other pieces bring the camp at Etah and years spent there to life right there in the lab.

Looking at a crack in the skin covering of a model kayak we found ourselves immersed in a discussion of how one would have dealt with such a problem in a full sized kayak in preparation for a walrus hunt.

One of the most surprising artifacts came up while we were examining a group of specimen boxes. We opened and catalogued box after box of eggs. But then we came across one box labeled “young of Tringa cauntus.” Curiously we opened it to find small stained envelopes inside. Not sure of procedure, we called Genny and waited for her to proceed.

Carefully, Genny opened the first envelope and pulled out a hundred year old baby bird specimen.

Just another day at the Arctic Museum.

A Crocker Land Expedition Who’s Who

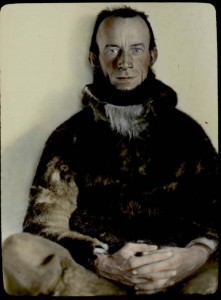

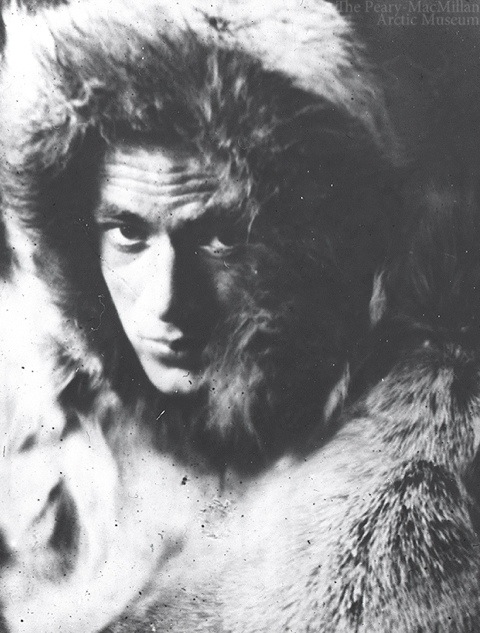

A major expedition such as the Crocker Land Expedition (CLE) involves many people at home and in the field, but the official members of the expedition inevitably draw the most attention. We will be writing about a wide variety of people in this blog, but this seems a good time to introduce the expedition members. The full stories of their many adventures on the expedition will emerge as we delve into their papers and journals, but this can serve as a ‘pocket guide’ to the key players

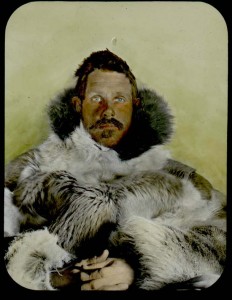

Donald Baxter MacMillan, an 1898 graduate of Bowdoin College, became the sole expedition leader after the death of George Borup. In 1913 he abandoned his graduate studies in anthropology at Harvard to devote himself to organizing the expedition. His northern experience at the time included a year with Peary on the 1908-09 North Pole expedition and three summers in Labrador. You can read more about him here.

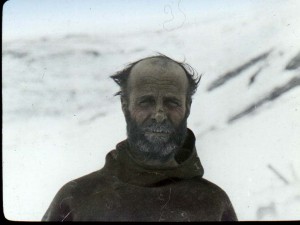

Walter Elmer Ekblaw (1882-1949) was teaching at the University of Illinois when he was appointed geologist and botanist with the CLE. Through his participation the university became one of the sponsors of the expedition (with AMNH and the AGS). He published extensively on his research when he returned home and went on to complete a PhD in Geography at Clark University, where he taught until his death in 1949. His grandchildren recently donated a terrific archive of his Crocker Land papers, photographs and other material to the museum, so you can expect to read a lot more about him in this blog.

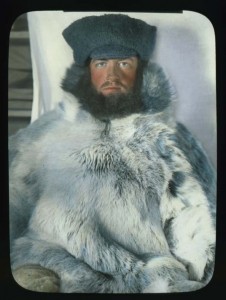

Maurice Cole Tanquary (1881-1944), also a graduate of the University of Illinois and a friend of Ekblaw’s, taught at Kansas State Agricultural College when he was appointed zoologist for the expedition and returned there after the expedition. His primary area of specialization was entomology, and in later years he became renowned for his work with commercial beekeeping. Tanquary’s family donated his photographs, lantern slides and journals to the museum in 2006.

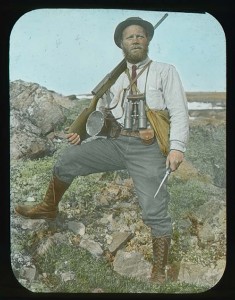

Harrison J. Hunt (1878-1967), another graduate of Bowdoin College (Class of 1902), was hired as the surgeon/physician for the expedition and was one of the expedition’s most avid hunters. He had a successful medical career in Bangor, Maine on his return home. In 1980 his daughter, Ruth, published a book, North to the Horizon: Arctic Doctor and Hunter, 1912-1917, based on his journals and reminiscences.

Fitzhugh F. Green (1888-1947) was a graduate of the US Naval Academy at Annapolis (1909). He was an Ensign in the US Navy when he was appointed as Civil Engineer for the Crocker Land Expedition. He was also responsible for taking astronomical observations. After this expedition he went on to have a long career with the Navy and became a writer. His books include a biography of Robert E. Peary and an account of his experiences on the Crocker Land Expedition. Green’s papers are held by the Georgetown University Library, and some of his CLE journals are housed at Bowdoin College and the AMNH.

Jerome Lee Allen was the electrician and wireless operator for the expedition. He oversaw electrification of the expedition quarters, as well as installation of a telephone system, both ‘firsts’ for such a northerly location. His chief responsibilities were to maintain the batteries that ran the electricity and install and operate a wireless station to both send and receive messages. Had the communication system worked it would have been another, and more important, first. Sadly, for reasons largely beyond his control, his efforts were not rewarded. He went on to work with radio and other technologies for the US Navy, where he had a long and distinguished career.

Jonathan “Jot” Small, a boat-builder and childhood friend of MacMillan’s, was the expedition’s cook and all-round handyman – though everyone agreed he was a much better handyman than cook. He was employed by the Toppan Boat Manufacturing Company and went on a number of MacMillan’s expeditions both before and after Crocker Land. Eventually Small returned to Provincetown, his childhood home, where he opened a boat-building shop.

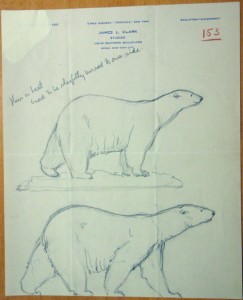

The Bowdoin Bear

Throughout his career, MacMillan never forgot his alma mater, Bowdoin College. One of his first, and best-loved tributes to the college is the famous Bowdoin Bear, the college’s athletic mascot. According to college lore Bowdoin alumni, MacMillan among them, selected the polar bear as the mascot at an alumni association dinner in New York in 1913. MacMillan procured the bear during the Crocker Land Expedition and presented it to the college in 1918, where it has presided over athletic events ever since.

Given the bear’s history, we were delighted, if not surprised, to find some interesting correspondence relating to its history among the Crocker Land Expedition papers in the Archives at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

Chronologically the first of these was a letter to MacMillan from Bowdoin athletic director Frank Whittier dated May 10, 1913 requesting a bear. Commenting on the extraordinary success of the Bowdoin athletic teams, Whittier reported that he just ordered a new trophy case for the gymnasium. He noted, “If we keep on at this rate, the only thing that we will need to complete our trophy room will be a fine, stuffed polar bear skin. I hope you will be in the way of helping us to get that.”

We have long known that MacMillan kept this request in mind during his four years in the North, and that he shot the bear near his base at Etah in the spring of 1915 (May 13, to be precise). Records in the Arctic Museum’s collection reveal that the well-known hunter Nookapingwa was MacMillan’s companion on the hunting expedition. (You can read more about Nookapingwa here).

The bear skin, like other specimens collected by expedition members, must have been cleaned and salted for preservation while it awaited shipping. In the spring of 1915 the men still expected to be home that summer, or most certainly the following year. In fact, they did not get home until 1917. Despite the delays, the skin survived and with all the other specimens was turned over to the AMNH in the summer of 1917.

MacMillan’s commitment to the expedition was such that he volunteered his time and received no salary for his four years’ work. The museum administration wanted to show its appreciation in some way, however. MacMillan requested that they mount the bear skin he had identified as being for the College at the museum’s expense, and ship it to Bowdoin as a gift from MacMillan. This they agreed to do. They sent the skin to their stellar taxidermist James. L. Clark, a student of Carl Akeley, who mounted many of the animals still on view in the AMNH today.

Clark’s work was complicated by the fact that the skin was not in terrific shape (perhaps due to its long period in storage) and that MacMillan was in a hurry – he wanted the mount to arrive at Bowdoin in time for Commencement in 1918, when MacMIllan was to be presented with an honorary degree. Clark was up to the task, however. Given the state of the skin he recommended a simple pose, noting in his letter that such poses are usually best anyway. He sent MacMillan a few sketches of poses to select from, and reiterated his advice about simplicity, also noting that the head would be “slightly turned to one side.”

MacMillan concurred, and selected the now familiar pose of the bear. His anxiety about the arrival of the shipment is revealed in a number of letters and telegrams inquiring about how the work of mounting and shipping were progressing. The final telegram finishes the story: the bear arrived in time to be presented to President Sills at the Commencement dinner, June 1918.

Standing outside Morrell Gym in the Buck Center, right by the trophy cases as Whittier would have wished, the bear holds a special place in the hearts of many Bowdoin alums, living up to MacMillan’s wish when he presented it to the college: “May his spirit be the Guardian Spirit not only of Bowdoin Athletics but of every Bowdoin [person].”

At the Archives

We are finishing up our preliminary work in the AMNH archives today, overwhelmed at the volume of material, but with a much better idea of what we have ahead of us. In the coming weeks we’ll be posting commentary about some of the treasures we found as we process all this information.

As you might expect of a large institution, the volume of correspondence the expedition produced is tremendous. In archival terms this translates into 11 linear feet of file boxes, each filled with folders of papers. For those who have grown up with electronic records and communication, and even those for whom photocopiers seem to have been around forever, the labor these records represent is staggering.

What would be a quick email or text exchange today, then generated a series of formal letters, or in urgent cases, telegrams. Letters are mostly typed with one or more carbon copies, the original “cc’s.” Even handwritten correspondence is sometimes accompanied by a typed transcript, a godsend when the original author’s scrawl is difficult to decipher. Clearly many typists spent many hours at this work. Questions that could be answered with a quick Google search today required letters sent, and replied to; brochures for equipment requested and sent; and detailed estimates of the costs of everything from photographic film to hardware sent, approved, and acted on.

The files include correspondence on all aspects of the expedition, from MacMillan’s first formal proposal in 1911 to completion of reports in the 1920s. If it was written down, it was saved and filed, a detailed window onto the institutional culture and the workings of a major scientific expedition in the first quarter of the twentieth century. At this point we have done a broad survey of the papers, in preparation for more focused research later. Still, even as we quickly paged through 1000s of documents significant tidbits of information jumped out, potential leads for further research, and answers to niggling questions. Stay tuned for updates soon!

One hundred years ago…

Although this blog is inspired in part by the impending centennial of the Crocker Land expedition, we do not intend to post a stream of “on this day, one hundred years ago” facts. Nevertheless, some days are worth noting, and May 15 is one of them.

By the spring of 1912, preparations for the imminent departure of the expedition were well on their way. A ship, the Diana, had been chartered, supplies had been purchased, and although there was still lots to do, including raising more funds, everything was looking good. But in April, tragedy struck. George Borup, the charismatic young co-leader of the expedition drowned in a boating accident.

At first, Borup’s sudden death threw the plans for the expedition into confusion. Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the AMNH, formally proposed that the expedition be called off, and that they offer the funders the option of having their money returned or of having it transferred into an endowed memorial fund. Edmund Otis Hovey, chairman of the Crocker Land expedition committee and curator of geology, along with other committee members, successfully argued against this course of action and proposed postponing the expedition for a year, and then going forward with MacMillan as sole leader. George Borup’s father joined the discussion, advocating for postponement rather than cancellation. One hundred years ago, on May 15, 1912, the committee formally accepted this proposal.

In the following weeks and months, preparations continued, including the search for a geologist to replace Borup. Some financial losses were inevitable, such as the penalty for canceling the Diana charter at short notice, but fund-raising also proceeded, to put the expedition on good financial footing.

Everyone concerned felt Borup’s loss, and there was some debate over how to adequately recognize his contribution. In the end, the Crocker Land Expedition became The George Borup Memorial Expedition. Osborn named a museum launch after him, MacMillan named the research station they built in 1913 Borup Lodge, and later, the expedition named a fjord on Ellesmere Island after him.

Beginning at the Beginning

Manhattan, warm and rainy in mid-May, is a long way from the Polar Sea, but if we are to study the Crocker Land expedition, this is the place to begin. Almost as soon as they returned from their first northern adventure as “tender feet” with Robert E. Peary’s North Pole expedition in 1909, George Borup and Donald B. MacMillan were planning a new expedition. Their goal was to find Crocker Land, an island sighted by Peary to the north and western of Axel Heiburg Island. Such an expedition is not to be undertaken lightly, and the two men soon began looking for sponsors. One of the first places they looked to was The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), in New York. As early as 1911, MacMillan wrote to them suggesting they sponsor a two-year expedition. Ultimately the AMNH did sponsor the expedition, which is why we have come here, to study the papers, photographs and other materials in the museum’s archives, and to learn more about how the expedition took shape.

While the expedition is named for the geographic region MacMillan and Borup intended to investigate, their goals were broader and more scientifically focused. This was in keeping with contemporary trends in exploration, as the unknown areas of the world map were filled in and people turned their attention to understanding the people, animals and plants that inhabited them. In 1911 Borup was a graduate student in geology at Yale, while MacMillan was studying anthropology at Harvard. Their plan was to travel north in the summer to be ready for an early spring sledging trip across the frozen ocean to Crocker Land. In the months prior to this trip, and for the year following, they would conduct scientific research. In 1911 MacMillan estimated that this could be accomplished for about $15,000.

As we know, in broad outline, this is indeed what happened, but not without a lot of ups and downs along the way. Over the next months and years, we will document our studies of this expedition, looking at it from a variety of perspectives and providing glimpses of both how the expedition itself developed, and how our own exhibit research progresses.