Previously we mentioned the recently donated collection of materials belonging to W. Elmer Ekblaw. Today we have a guest post from one of our interns, Alex Brown ’13, who has been working with the collection since September. This summer she is working at the museum as a Gibbons Intern helping us in the early stages of developing an interactive component of our Crocker Land exhibit. Here she describes some of the adventures she and Annie Streetman ’12 had last year while working with the Ekblaw collection.

Interning at the Arctic Museum, by Alex Brown, ‘13

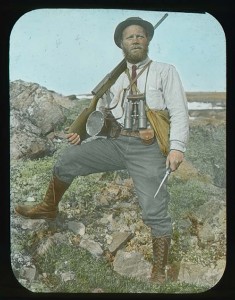

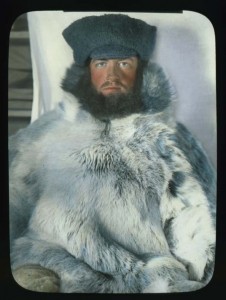

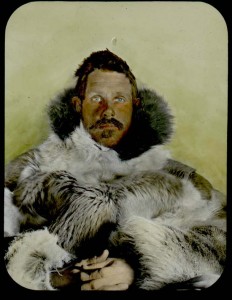

In September of 2011 the grandchildren of W. Elmer Ekblaw donated a collection of material relating to the 1913 Crocker Land Expedition. The gift includes journals, papers, books, specimens, and an abundance of artifacts. For the last year, the museum has been studying and processing the collection in preparation for an exhibit planned for 2014. Annie Streetman ’12 and I spent many hours working on the collection during the 2011-12 academic year.

When we first encountered the Ekblaw collection it appeared to consist of boxes of stuff. Over the last year as we sorted and catalogued we came to know the collection intimately. Our journey began with preliminary inventory and the daily mystery of uncovering the true identity of objects. It felt like a real life game of pictionary.

For instance, the object resembling a pencil sharpener turned out to be a device for sharpening razor blades and knives. On the other side of the spectrum, some objects such as the forceps matched modern tools right there in the lab. Every artifact was meticulously examined, catalogued and labeled. Writing condition reports proved a challenge for some artifacts; for instance, how does one describe a box of rocks? (We went with “rocky!”)

We learned how to distinguish walrus ivory from narwhal ivory, and got into a long debate about whether the objects in a jar were polar bear claws or bird beaks (which look surprisingly similar in a old glass jar). A few hours later our curator, Genny, answered the question for us.

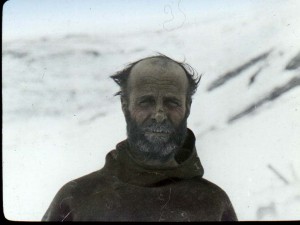

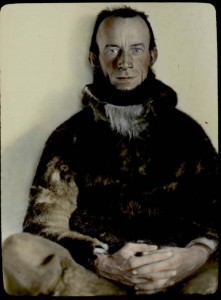

Elmer Ekblaw kept meticulous records of his time in the north. As the most productive scientist on the expedition, he studied geology, botany, ornithology, glaciology, and even anthropology. A combination of scientific and personal objects make up the collection. When going through it, some pieces almost make you feel as if you yourself are preparing for you own expedition north. Other pieces bring the camp at Etah and years spent there to life right there in the lab.

Looking at a crack in the skin covering of a model kayak we found ourselves immersed in a discussion of how one would have dealt with such a problem in a full sized kayak in preparation for a walrus hunt.

One of the most surprising artifacts came up while we were examining a group of specimen boxes. We opened and catalogued box after box of eggs. But then we came across one box labeled “young of Tringa cauntus.” Curiously we opened it to find small stained envelopes inside. Not sure of procedure, we called Genny and waited for her to proceed.

Carefully, Genny opened the first envelope and pulled out a hundred year old baby bird specimen.

Just another day at the Arctic Museum.