Today we present another guest post, this one from museum intern Meg Bunke ’14. Meg began working at the museum this summer and together with Alex has delved deeply into the Ekblaw collection. Here she reflects on some of what she has gleaned from her work.

The Man Behind the Journals by Meg Bunke, ’14

In the time I have spent going through Elmer Ekblaw’s artifacts and reading his journals this summer, I have come to feel as if I know him personally. Many of his letters and items hold a happy connection for me because they refer to my hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, where Ekblaw lived and taught at Clark University for many years. His pair of nifty foldable glasses, made by opticians in Worcester, were small enough to take along on the expedition. Among his books was one checked out from the Worcester Public Library, which the museum curator recently returned to them––many years overdue!

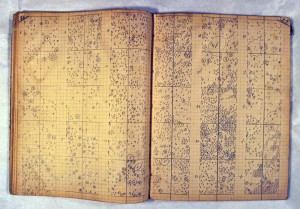

I appreciate Ekblaw’s meticulous records about the rocks, birds, plants, and geography of Ellesmere Island, not only for the information he collected but also for the candor and humor that comes through in his writing. Some of his scientific entries are aesthetically beautiful, like this schematic of the location of various plants, each marked by a number:

Pages from one of Ekblaw's notebooks showing the distribution of plant species in carefully measured squares.

His sometimes-playful writing demonstrates a childlike excitement in his Arctic experiences. Ekblaw revels in building his first cairn on a sledging expedition along Canon Fjord in April 1915. He proudly announces that it makes him feel “like a real explorer!”

His commentary about interactions with other crew members or with his dogs add humor to his journals, as in this excerpt from January 3rd, 1917:

“Knud Rasmussen and Neheteslasook slept in our tent this night, disturbing our domestic arrangement very much. There is no sleeping in the tent that K. R. occupies for he talks all the time.”

In another journal, he tells a sad story about an eider duck he observed while going for a walk along a fjord. The “young king eider had waddled from one iceberg pool to another in search of open water. When we found him he was so nearly fatigued that when we tried to catch him, he dived under the ice and was unable to get back and so drowned.”

The Crocker Land trip may have lasted much longer than Elmer Ekblaw expected, but his writing reveals sustained enthusiasm for his endeavors. His tales of everyday experiences in the Arctic are funny and touching, and his excitement over his first Arctic voyage is contagious.