Throughout his career, MacMillan never forgot his alma mater, Bowdoin College. One of his first, and best-loved tributes to the college is the famous Bowdoin Bear, the college’s athletic mascot. According to college lore Bowdoin alumni, MacMillan among them, selected the polar bear as the mascot at an alumni association dinner in New York in 1913. MacMillan procured the bear during the Crocker Land Expedition and presented it to the college in 1918, where it has presided over athletic events ever since.

Given the bear’s history, we were delighted, if not surprised, to find some interesting correspondence relating to its history among the Crocker Land Expedition papers in the Archives at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

Chronologically the first of these was a letter to MacMillan from Bowdoin athletic director Frank Whittier dated May 10, 1913 requesting a bear. Commenting on the extraordinary success of the Bowdoin athletic teams, Whittier reported that he just ordered a new trophy case for the gymnasium. He noted, “If we keep on at this rate, the only thing that we will need to complete our trophy room will be a fine, stuffed polar bear skin. I hope you will be in the way of helping us to get that.”

We have long known that MacMillan kept this request in mind during his four years in the North, and that he shot the bear near his base at Etah in the spring of 1915 (May 13, to be precise). Records in the Arctic Museum’s collection reveal that the well-known hunter Nookapingwa was MacMillan’s companion on the hunting expedition. (You can read more about Nookapingwa here).

The bear skin, like other specimens collected by expedition members, must have been cleaned and salted for preservation while it awaited shipping. In the spring of 1915 the men still expected to be home that summer, or most certainly the following year. In fact, they did not get home until 1917. Despite the delays, the skin survived and with all the other specimens was turned over to the AMNH in the summer of 1917.

MacMillan’s commitment to the expedition was such that he volunteered his time and received no salary for his four years’ work. The museum administration wanted to show its appreciation in some way, however. MacMillan requested that they mount the bear skin he had identified as being for the College at the museum’s expense, and ship it to Bowdoin as a gift from MacMillan. This they agreed to do. They sent the skin to their stellar taxidermist James. L. Clark, a student of Carl Akeley, who mounted many of the animals still on view in the AMNH today.

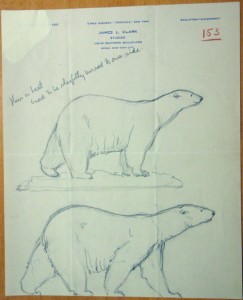

Clark’s work was complicated by the fact that the skin was not in terrific shape (perhaps due to its long period in storage) and that MacMillan was in a hurry – he wanted the mount to arrive at Bowdoin in time for Commencement in 1918, when MacMIllan was to be presented with an honorary degree. Clark was up to the task, however. Given the state of the skin he recommended a simple pose, noting in his letter that such poses are usually best anyway. He sent MacMillan a few sketches of poses to select from, and reiterated his advice about simplicity, also noting that the head would be “slightly turned to one side.”

MacMillan concurred, and selected the now familiar pose of the bear. His anxiety about the arrival of the shipment is revealed in a number of letters and telegrams inquiring about how the work of mounting and shipping were progressing. The final telegram finishes the story: the bear arrived in time to be presented to President Sills at the Commencement dinner, June 1918.

Standing outside Morrell Gym in the Buck Center, right by the trophy cases as Whittier would have wished, the bear holds a special place in the hearts of many Bowdoin alums, living up to MacMillan’s wish when he presented it to the college: “May his spirit be the Guardian Spirit not only of Bowdoin Athletics but of every Bowdoin [person].”