What did Galileo’s texts sound like to his readers? Was his language erudite or common? Literary or scientific? Dated or full of neologisms? Full of hidden citations that would have been recognizable to a courtly audience? Breaking new ground in the expression of mathematical concepts? These questions align well with computational text analysis processes for historical text reuse and for natural language processing (NLP). Historical text reuse relies on identifying similar phrasing, even with the use of different tenses or subjects of verbs or synonyms. Using NLP to find outliers as well as clusters of genres, styles, or chronological groups relies on models of syntax derived from word order and word forms. Unfortunately, the underlying tools for these methods are built from modelling modern Italian texts, typically from news outlets. Modern Italian and pre-modern Italian have distinct characteristics, some of which are related to spelling, others to word order, but also how words like verbs are formed.

Take the example of Galileo embedding a slight modification of a line of poetry in his treatise on comets. He describes his opponents as “empiendo il ciel di strida e rumori” (filling the sky with shrieks and noise). The implicit suggestion, based on the context in the poem, is that the philosophers who disagree with him are like obnoxious birds at an outdoor banquet, but the poem also implies that these birds are like the Saracen warriors attacking Christian cities. The gerund “empiendo” comes from empire, an old form of the verb now more commonly expressed as riempire. The noun “ciel” is an abbreviated form of “cielo” or sky, a frequent form of truncation in early modern Italian. The shrieks (strida) are more likely to be expressed as grida (cries) in Italian. Based on my testing of common NLP models for Italian, most of these words are considered “out-of-vocabulary” (OOV). Here is an example from a few leading models that I presented at MLA in 2025:

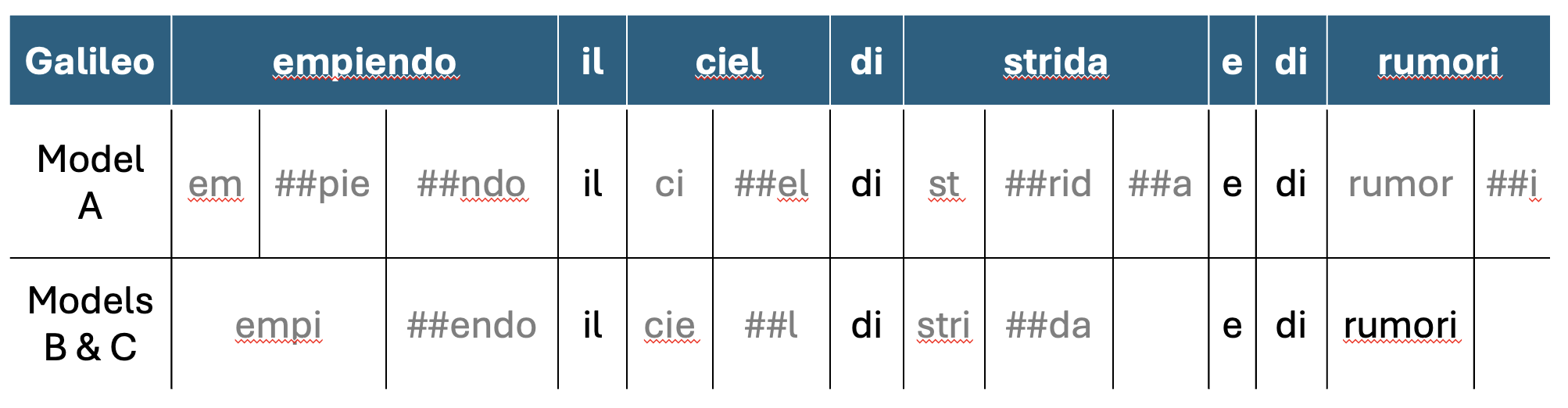

Comparison of sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2 (Model A) to efederici/sentence-BERTino and dbmdz/bert-base-italian-xxl-cased (Models B & C). Gray words were out-of-vocabulary and parsed as seen.

The strength of LLMs to find similar contexts of use, identify synonyms, or match historical text reuse are diminished to the point where the value of their use is minimal.

In one way or another, out-of-vocabulary words have been the focus of my research since first trying NLP with Galileo’s texts in 2018 and now with large language models (LLMs). Reconciling the power of machine learning (and thus LLMs) with the complexities of older language has required developing a lexical data set from the texts in Galileo’s library. This data set captures the features of Italian necessary for detecting hidden quotations and expressive similarities between what he wrote and what he read.

Historians of Italian have produced excellent resources for consultation, but they are not easily usable as data sets. So, while the online historical dictionary Tesoro della Lingua Italiana delle Origini (TLIO) may contain many of the forms of words found in the books in Galileo’s library, the webpage formatting has never been conducive to automated datafication. Alternatively, the 2001 iteration of the searchable 1612 edition of the Vocabolario della Crusca (http://vocabolario.sns.it) had highly structured entries using HTML tables and a regular URL structure. (The site is no longer accessible, but an alternate, unsearchable version can be viewed through the site of the Accademia della Crusca: Lessicografia della Crusca in rete: Dizionario 1o edizione.) Since Galileo’s uses of some terms found their way into later editions of the Crusca, and it was published at the same time as his Italian works on floating bodies and sunspots, I started there.

Inquiries to the team members listed on the credits page for searchable version of the online project went unanswered in 2019. My script checked that bots were allowed on the site for scraping data, but, to avoid infringing on the intellectual value of their current and future versions of the digital dictionary I am not making the Crusca data available or identifiable in the lexicon data that I am creating. To further distinguish my resource from the existing ones, the available digital versions of the 1612 Vocabolario della Crusca do not systematically identify parts of speech; my lexicon data does not reveal definitions or the usage examples in the entries.

I wrote code to automatically assign a preliminary part of speech to each entry and then clean the initial set of 24,560 words. Any entry that did not fit the rule for any part of speech category (i.e. a noun that ended in -i) was flagged for manual review (by me). Articulated prepositions (e.g. nelle) and irregular verbs were expanded by hand (by me). I wrote R code to create automatically: the plural and truncated forms of nouns (accounting for irregular forms); gendered, numbered, superlative, and adverbial forms of adjectives; superlatives in the initial data were used to create adjectives and adverbs; verbs expanded into gerunds, past participles, present progressive, and all forms of present, imperfect, remote, future, conditional, present subjunctive, and imperfect subjunctive. Given the early modern prevalence of adding object pronouns to the ends of participles, gerunds, and subjunctive forms, those variants were also created (e.g. avendolo). This means that each verb is represented by more than 164 forms, sometimes more when known spelling variants were added.

This resulted in a data set of more than 1 million terms labeled with their part(s) of speech, root form, and tenses (where applicable). Admittedly some of the forms in the data are never used in spoken or written Italian. This is not a strict model of the language; it is a model for studying texts written in the language.

To improve the strength of this model, I have been iteratively comparing the vocabulary of texts for the “Galileo’s Library: Basic TEI Editions” project to the lexicon. As each new TEI file is completed, I identify matches in the existing lexicon and tag the terms that are not present. This has added only 25,000 terms to the lexicon, more than one third of which have been numbers, proper nouns, or foreign words. In many cases this method also identifies frequent typographical errors. Notably, the Italian translation of the Latin translation of an Arabic mathematical introduced line segments and other genre-specific terms to the lexicon, which explains the plunge in the middle of the graph below.

Importantly, students can help with this step of the work much more easily than cleaning the OCR. First-year Italian students can distinguish parts of speech very quickly. This may also be an opportunity for students to partner with large language models to confirm output. Cleaning and updating continue.

Research outcomes using the data set:

“Galileo Visualized” represents a collaboration with a student, Richard Ohia, to use the lexicon data to explore Galileo’s 1623 work on comets Il Saggiatore.

Planned outcomes specific to this data set:

The data includes nearly 2,000 proper nouns, which makes cleaning these and other early modern Italian texts much easier. By removing names, we can avoid being overly specific with clustering based on characters or geographic locations. This data will be shared once we complete the integration of the TEI files.

Publishing the data set via Journal of Humanities Data.