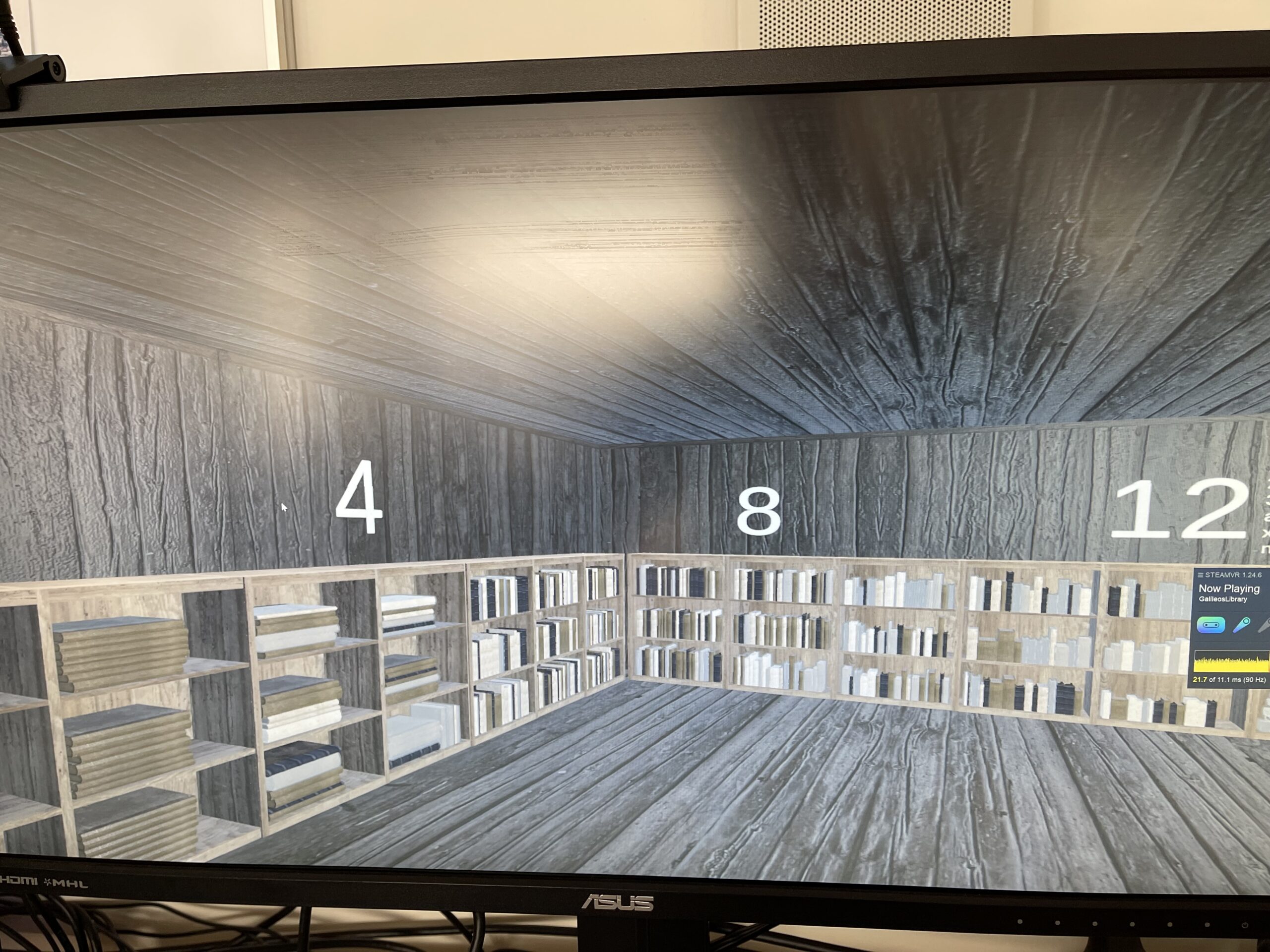

Galileo’s Virtual Library (GVL) currently is an austere virtual reality (VR) room lined with bookcases that can be filled in various ways with digital, three-dimensional (3D) representations of the nearly 700 books owned by Galileo Galilei (1563-1642).

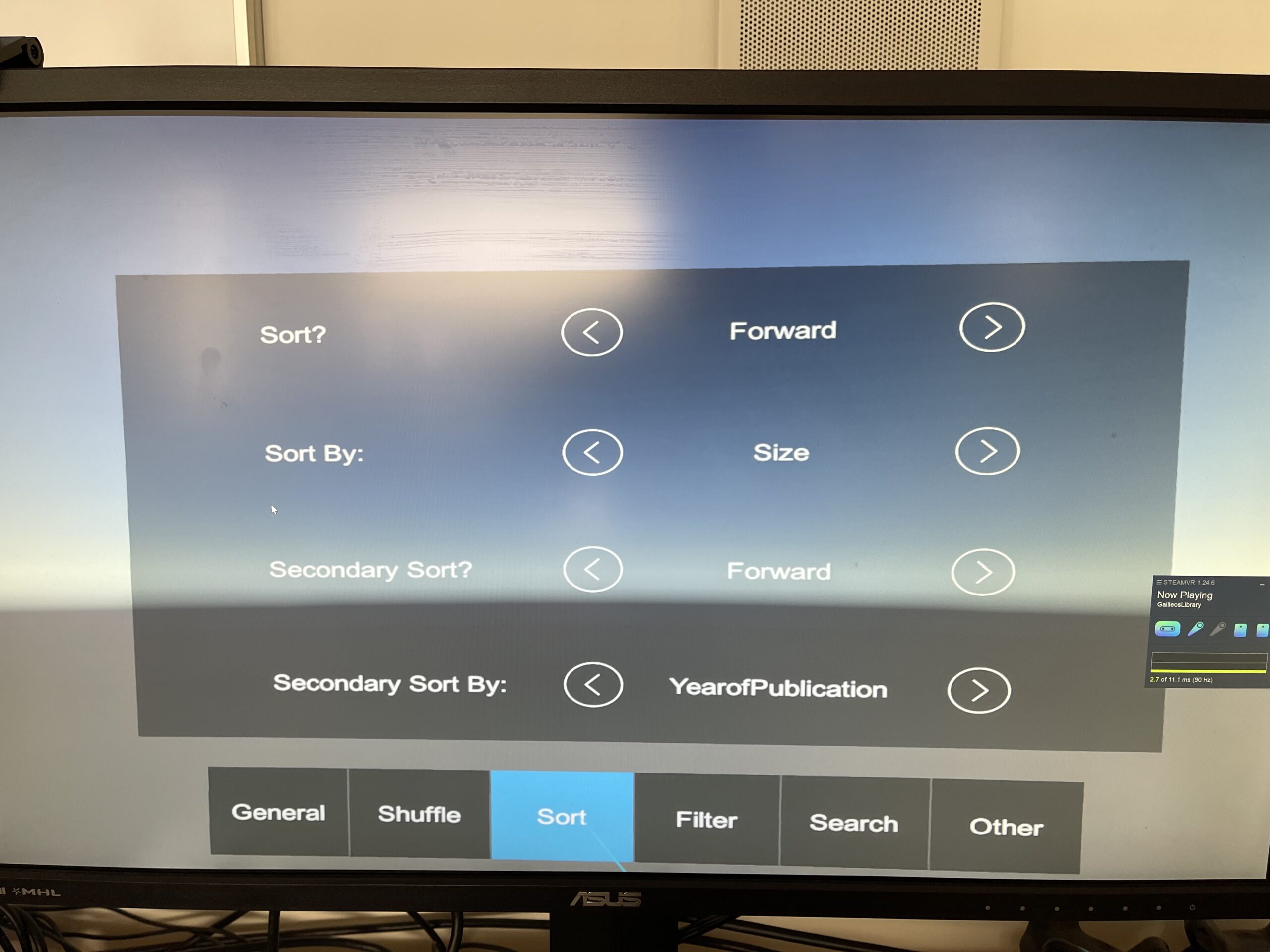

Visitors can sort, filter, search, and select volumes off the shelves to explore the collection. The project goals are twofold: learn more about Galileo’s library through the process of developing this digital representation and use the representation to engage with questions in the fields of digital humanities, history of the book, and Italian Studies. The motivating question behind GVL is: Can an immersive, three-dimensional environment offer new ways of understanding a lost collection of books? In the process of building it and testing it, a second, equally motivating question emerged: Can the lessons of GVL be applied to the study of digital collections more generally? What we found was that the process identified new historical questions about Galileo, alternative methods for representing complexity of data, and a way to design for uncertainty and ambiguity that is often part of humanistic data. After a brief introductory video, more details on the data, contextual rationale, and outcomes follow.

Thanks to internal funding from Bowdoin College, this project exists currently as a utilitarian proof-of-concept built on the 3D creator platform Unity by Matt Donnelly, a 2022 Bowdoin graduate. It is only accessible in the VR Lab at Bowdoin.

Link: Narrated overview of the project, with thanks to Colin Kelley for the video and sound editing. (Directs to an external site.)

In terms of content, Galileo’s Virtual Library is an opportunity to learn about books as representations of a time, place, and means of production in addition to their content. Underlying databases often treat material aspects of books as separate or even subordinate characteristics in comparison to titles, authors, and content. (Note that in the video size is being used as an inaccurate substitute for format.) Additionally, as with many other aspects of pre-modern Italian culture, editorial and analytical practices of the nineteenth century play an outsize role in shaping the interpretation of these primary materials. Keeping in mind the tenets of Leah Marcus’ Unediting the Renaissance (1996), the Galileo’s Library teams, even prior to exploring a VR model, worked to avoid recreating the hierarchies and priorities of cataloging practices at the turn of 1900. Instead, the data in GVL focuses on what the books had to say for themselves: all of the words on the title pages; dates as represented; formats and page layouts; printed marginalia and other paratexts; authors and addressees of dedicatory letters, poems, and epigraphs; numbers of inquisitors; and all named agents of a press or publisher. As a result, possible interpretative pathways in GVL include examinations of material properties of books written by authors born after Galileo, only books that use roman numerals to express dates, the printers of books with the most prefatory poetry, and other subcategories of the collection that cut across what are often unsurpassable boundaries in library catalogs.

Data and Metadata

Just before COVID-19 disrupted travel, I began a 3-year process of opening and turning the pages (or a digital representation of them) in every book thought to have been in Galileo’s collection. This resulted in 35 categories of metadata. Importantly, in nearly all cases, the data is partial, incomplete, or missing, posing valuable challenges for using or designing technology that can represent the collection.

Given the quantity of prior research, the Spring 2022 project required minimal data creation to establish the proof-of-concept, even though data collection and cleaning has continued. Most intensive was time spent in Bowdoin’s Special Collections & Archives to measure the dimensions of early European books. Matt was then a senior, and since he had been directly involved in the creation of Bowdoin’s VR Lab prior to and during the pivot to remote learning necessitated by COVID-19, he had the necessary expertise to be a valuable partner. Given the promising findings with what he completed in the spring, he continued the work as a contractor after graduation through his company Rising Tide VR Solutions.

Contexts in the Fields

Existing virtual libraries typically adhere to one of two categories: either static representations of collections of books and objects or interfaces for finding and/or viewing materials. To be sure, projects such as Leonardo’s Library by the Galileo Museum offer a valuable view of a dispersed collection of manuscripts and books. Visitors can experience a visual representation of Leonardo da Vinci’s homes and snippets of information about each title. The Galileo Museum in Florence, Italy also maintains an interface for the Biblioteca di Galileo (Galileo’s Library), but users must know search terms of interest to start the research process and the related bibliographic categories are limited to author, title, publisher, date, and sources, where available. Results are presented as typical digital catalog entries, with links to scans. (See “The Interactive Shelves” experiment that I conducted with Yassine Khayati ’25 as an alternative to traditional visualizations of book collections.)

GVL aims for more interactivity with the objects of study and attention to the material histories of the volumes for inquiry and understanding. This virtual library was made dynamic and responsive using Unity, software with extensive built-in measures to process input from the user that drives how the environment reacts. The input options build on the metadata categories, but full functionality is not yet available. The emphasis on metadata aligns with Rachel Sagner Buurma and Jon Shaw’s (2020) work on slow metadata in the Early Novels Database. Sagner Buurma, Shaw, and student collaborators have articulated the ways in which attentive description of volumes opens new vistas into understanding human expression through, for example, changing habits in notes and glosses, patterns of dedications, and networks of advertisers. The proof-of-concept for GVL focused on more traditional descriptors for books: author, title, publisher, date of publication, format, number of volumes, and number of pages. Yet, there are dozens of metadata fields to document, for example, the languages present in each text, kinds of imagery, how the text is sectioned and titled, and what kinds of printed marginalia exist.

In the more general area of VR projects, GVL must contend with the uncertain nature of the objects in the collection and their organization in innovative ways. By comparison, the recently funded Remastering the Renaissance: A Virtual Experience of Pope Julius II’s Library in Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura (Dotson 2019) connects the development space of Unity to the open-source publishing platform Scalar. The goal of the project is to recreate and annotate an extant space in the Vatican. The Virtual Studiolo project (Shemek 2018) from the IDEA Lab dedicated to Isabella d’Este’s collection of art and other cultural expressions is likewise bounded by the historical space in which it existed. Even NEH-funded VR projects such as Booksnake have focused on creating a digitized experience of an extant object. GVL does not try to recreate a historic space, but to recreate the books in an interactive space.

Project Outcomes to Date

Process

DH projects such as John Wall and collaborators’ Virtual Paul’s Cross have shown that the process of creating a 3D model can help to reveal previously unconsidered features of a lost architectural site, people’s actions within that space, and the historical documents that serve as primary sources to understand it. In one example of many, Wall (2014) and his team recognized the role of the cathedral bells in writing a sermon to be delivered as they chimed. Already in the GVL design process this has led to questions, for instance, about the rooms in Galileo’s Florentine homes, the amount of space that Galileo’s daughter-in-law would have needed to store books that she inherited, Galileo’s habits for having books bound, and how (in)frequently Galileo would have been immersed in his collection. This kind of relationship, between the digitization process and humanist’s goals of discovering, interpreting, and giving renewed voice to expressions and representations, has come to be seen as an ideal outcome in the field.

Representation – Complexity of Features

As a representation, admittedly, an elaborate bar plot could visualize much of the data about the collection. For instance, a bar plot that charts book sizes over time could color-code sections of each bar by publication location to indicate that in Galileo’s library large folio books printed in Venice were more common than those from Rome. But this would be visually overwhelming since Galileo’s books were published in more than 100 cities. The bar plot cannot show as immediately the comparison of number of pages, diversity of authors, and ranges of print dates. The underlying spreadsheet of data does capture all of this information, but trends can only be seen through filtering and sorting, which obscures the context of the entire collection.

Instead, immersion in the 3D environment provides a simultaneity that provokes inquiry through dynamic locations, dimensions, and proximities of the books to convey meaning. The books have space to be seen for their unique and common attributes alike.

Representation – Uncertainty in the Data

As mentioned, given the uncertainties surrounding many of the books in the collection, GVL is not designed to provide a stable, unchanging representation of the library. Every instantiation created a different order of the books and manuscripts on the shelves. Embedded in the design is Johanna Drucker’s (2012) counsel about resisting the ways in which visualization or datafication easily appear to be presentation of reality instead of representation of something variable, irregular, and incomplete. We capitalized on the affordance of the digital environment to make many models from the same data. Minimal details are available about how Galileo’s books were stored during his lifetime across multiple family homes and the library was dispersed even before his house arrest following his trial by the Inquisition for suspected heresy in 1633. Pre-modern book catalogs showcase a spectrum of details: from a simple count of books of a certain type to a partial title, from an author’s last name to complete bibliographic information about a printing. Rather than insist on one declarative, true or most accurate and fixed model of the library, we have built a digital space that invites evaluation and that constantly reminds us of its identity as created rather than recreated.

For extant copies with his handwriting in them, the historian has access to the full title, author, and imprint along with the material dimensions necessary to make a 3-dimensional surrogate. This project builds on Hall’s prior (2015) and current extensive research on the other books in the collection which are in three categories: titles with a known edition in Galileo’s possession at some point during his lifetime (482), those for which multiple editions are candidates (130), and those with such incomplete bibliographic information as to be unknown (81). In this sense, GVL offers a model for representing and experiencing lost collections, collections that never existed, books in inaccessible spaces, and libraries too fragile for regular consultation.

Yet, the technology resists this kind of indeterminacy. 3D models and VR applications most often recreate locations with a known physical footprint or allow for the expression of a fantastic vision for a space that cannot or may never exist (with no need for accuracy). Given the precision required to create a digital model, objects for which the data is incomplete are either omitted from virtual spaces or represented as though complete by filling in the blanks.

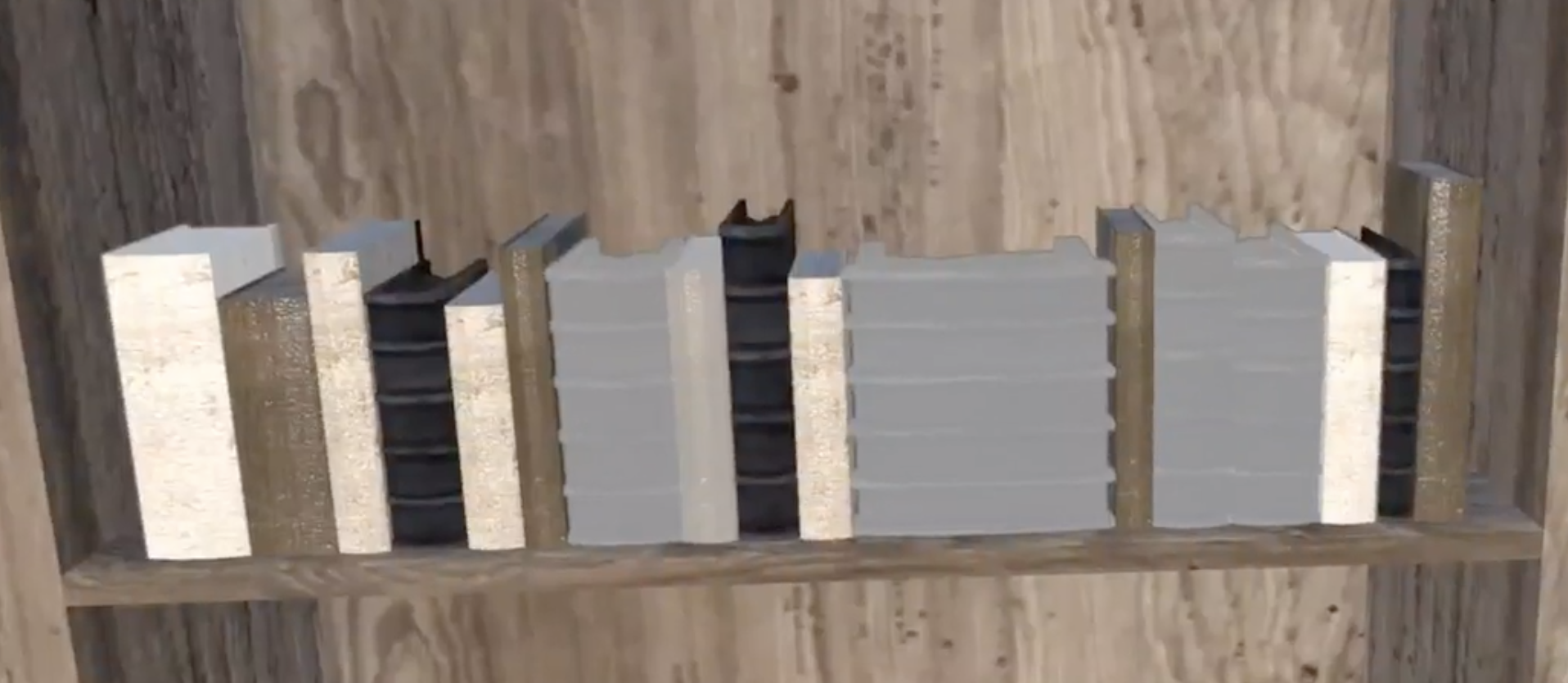

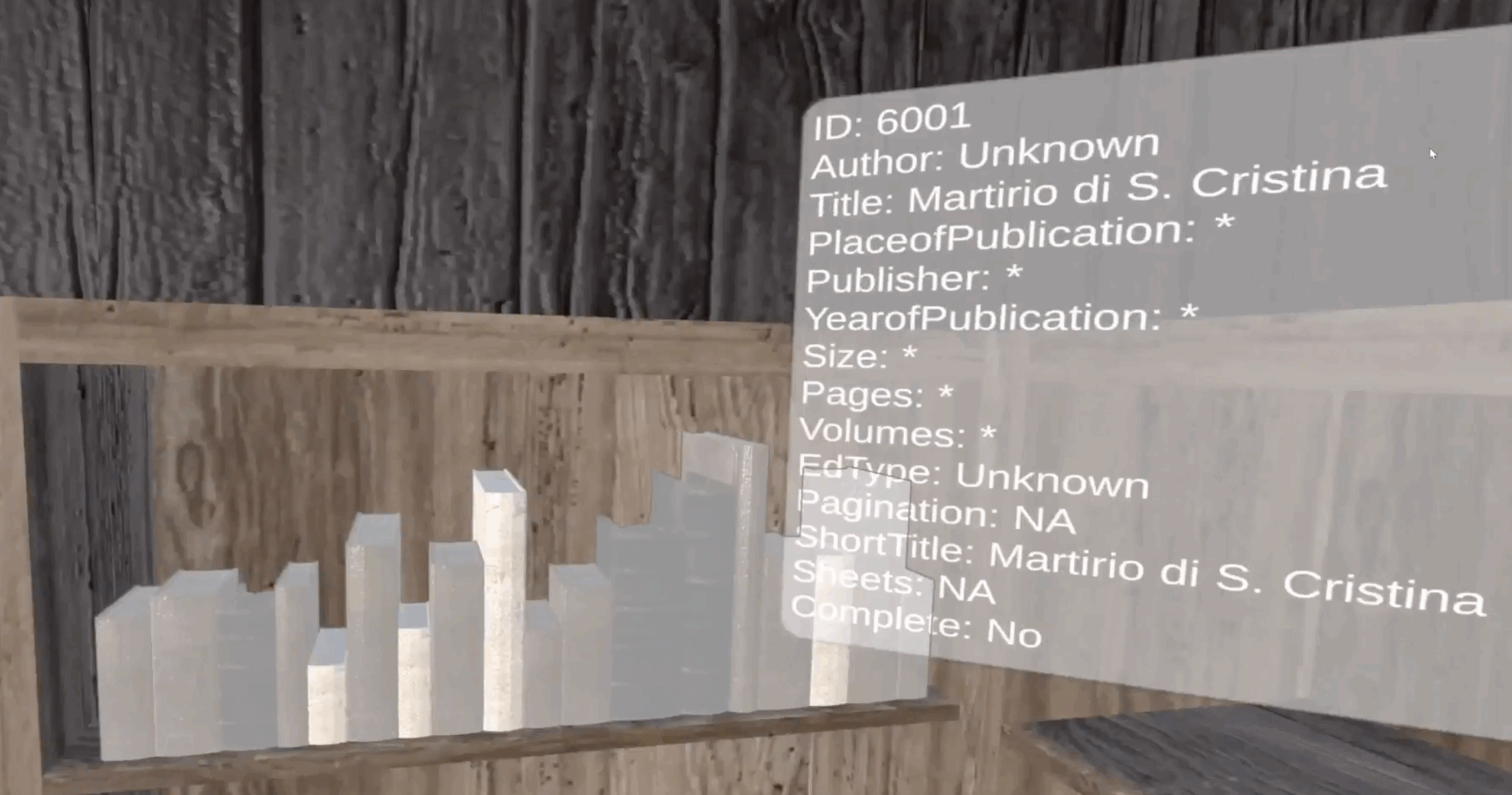

Our solution may sound cheeky: embrace the missing and incomplete as features, not bugs. Through contextualization, visualization, and, seemingly paradoxically, the instability of its representations, GVL engages the possibilities of missing data rather than omits the fragments. GVL is transparent about this uncertainty and incompleteness, allowing users to interact with representations of these undefined books that are shown with different bindings according to their status. Gray books are those with the least information about editions that Galileo might have owned.

Example of the visualization of books of different formats that are missing metadata for the sort criteria (and other metadata indicated by the *)

The visualization of these gaps in knowledge can thus lead to new knowledge. Additionally, books with incomplete physical data change appearance each time the model is created, using an algorithm that generates dimensions based on a normal distribution for a small sample of books measured in Bowdoin’s Special Collections & Archives (SC&A). Just the act of measuring a few books inspired what I hope will be a future project and/or class that explores datafication of the collection to aid with research and discoverability of materials at Bowdoin.

The aggregate result is a collection with book models that are mostly sized around the average value, with some larger and some smaller. This methodology recognizes the fact that the precise measurements of specific volumes are not known, and therefore each model’s size changes each time it is loaded. However, there are some size discrepancies in the models, with some being unrealistically large or small compared to the other size classes. Since complete historical accuracy of the representation is not possible, the user must focus more on model creation as the method of inquiry.

The Future for GVL

While GVL sits at the intersection of DH, history of science, history of the book, Italian Studies, and Galileo Studies, the project revealed a broader implications of experimenting with representation of information. Unexpectedly, feedback from my first-year writing seminar students indicated the value of a virtual research space like GVL for visual and kinesthetic learners approaching any established area of study in which they are novices. This small class is capped at 16, yet 12 responded with this observation. Since the platform allows multiple re-configurations and a 360o view of the results, students felt they could take in an entire intellectual landscape before engaging with specific content based on features of interest. Instead of an infinitely scrolling list of results, users see how each title fits (or doesn’t) within the entire collection. The humanistic skills of contextualization and differentiation are emphasized, fostering the ability to discover connections and meaningful pathways to knowledge making. As mentioned in the overview video, this is an exciting area for future research collaboration, perhaps not involving Galilean materials at all.

References

- Dotson, Bill. 2021. “NEH Grant to Support Virtual Experience of Pope Julius II’s Library.” USC Libraries. January 19, 2021. https://libraries.usc.edu/article/neh-grant-support-virtual-experience-pope-julius-iis-library

- Drucker, Johanna. 2012. “Humanistic Theory and Digital Scholarship.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold, 85-95. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minn. Press.

- Hall, Crystal. 2025. “Astronomy and Print Networks in Galileo’s Library” in The Changing Shape of Digital Early Modern Studies. Toronto and New York: Iter Press, eds. Randa El-Khatib and Caroline Winter. In press.

- ———-. 2017. “Galileo’s Ariosto: The Value of a Mixed Methods Approach to Literary Analysis,” Humanist Studies and the Digital Age. 5.1: 96-107.

- ———-. 2015. “Galileo’s Library Reconsidered,” Galilaeana, XII: 25-78.

- Hall, Crystal and Hannah Rafkin ’17. “Galileo’s Digital Library.” Digital Humanities Summer Institute. Victoria, British Columbia. June 2-6, 2014.

- Marcus, Leah. 1996. Unediting the Renaissance. London & NY: Routledge.

- Sagner Buurma, Rachel and Jon Shaw. 2020. “Slow Metadata.” PMLA 135.1: 188-194.

- Shemek, Deana, et al. 2018. “Renaissance Remix. Isabella d’Este: Virtual Studiolo.” DHQ 12.4 http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/12/4/000400/000400.html

- Wall, John N. 2014. “Transforming the Object of Our Study: The Early Modern Sermon and the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project.” JDH 3.1 (Spring). https://tinyurl.com/WallVPC2014

- ———-. Virtual Paul’s Cross Project. https://vpcross.chass.ncsu.edu/

- Witmore, Michael and Jonathan Hope. 2016. “Books in Space: Adjacency, EEBO-TCP, and Early Modern Dramatists.” In Early Modern Studies after the Digital Turn, edited by Laura Estill, Diane K. Jackaki, and Michael Ullyot. 9-34. Toronto: ITER Press.