Libraries are very much on my mind these days as I grapple with the best methodologies for reconstructing and visualizing Galileo’s library. I am also working constantly with digital collections: institutional libraries, archives of organizations, and single studies of authors. Perhaps it is no surprise then, that when first asked to suggest possible readings for the section of the Gateway to Digital Humanities Course that focuses on textual analysis, I immediately recommended Jorge Luis Borge’s “Library of Babel.”

To me this short essay represents many of the possibilities and pitfalls of digital and computational library studies. Borges imagines a library that holds one copy of every book that could possibly be written. Some contain gibberish, others perfect copies of known work. Scholars live in the library searching for answers to questions about human experience. Ideological camps form and battles ensue, but all the while, even this hyperbolically complete library remains enigmatic to its users due to its sheer size. In parallel ways, computers have the potential to create a similar digital library. Natural language processing has already shown that computers can generate prose that has the “sound” of known authors like Immanuel Kant. Programming loops (of the kind the Gateway to Digital Humanities students are applying to images) perform the same action repeatedly (changing one pixel at a time, for example) and could conceptually be employed to provide the infinite variety of texts that populate “The Library of Babel.”

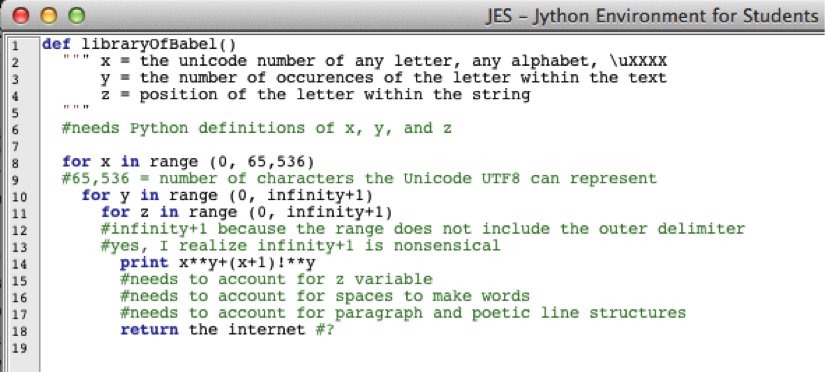

For readers of Python programming language, I tried to express this impossible program in loop terms in Jython. Strings and concatenation would help, but I think this still conveys the message in a light-hearted form:

The above attempt at code (that has legal syntax for Jython, but an error-filled program) is a futile approach for bringing order to chaos. Some Digital Humanities (DH) scholars would argue that digital and computational studies could offer partial solutions to comprehending and organizing this vast quantity of textual information. This is quite optimistic that estimates suggest 340 million new 140-character tweets on Twitter daily, not to mention the 3.77 billion (and growing) indexed pages on the world wide web.

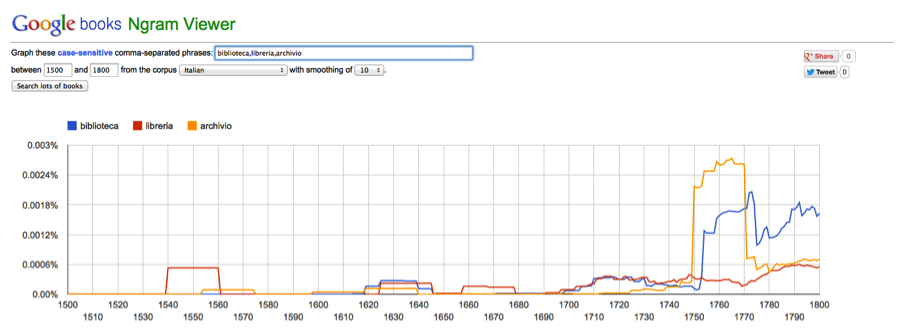

Working even with the available (and manageable) digital data, certain assumptions are made by tools and certain information is lost in their application, all of which gives me pause for thought as I reconstruct and try to find analytical pathways through the library of a person about whom ideological fields have been defined and passionate battles have been fought for centuries. Matt Jockers has led the field of DH with his work on Macroanalytics, currently focused on establishing patterns in nineteenth-century fiction, but relies on only the books for which a digital copy has been made. Google books Ngram Viewer allows users to compare the frequencies of words that appear in digital or digitized books during different time periods, which assumes consistency of cataloguing and meta-data entry across all participating institutions, which is not always the case.

As I revisit the data for my own project on Galileo, I wonder where I will enter the ideological disputes that surround the interested fields; I worry about what information will be excluded from the data; and how my users will navigate the digital library I am about to create.

Why are you taking the Gateway course?

Why are you taking the Gateway course? November 13, 2013 4:30 PM – 7:00 PM

November 13, 2013 4:30 PM – 7:00 PM