by Jordan Goldberg ’14.

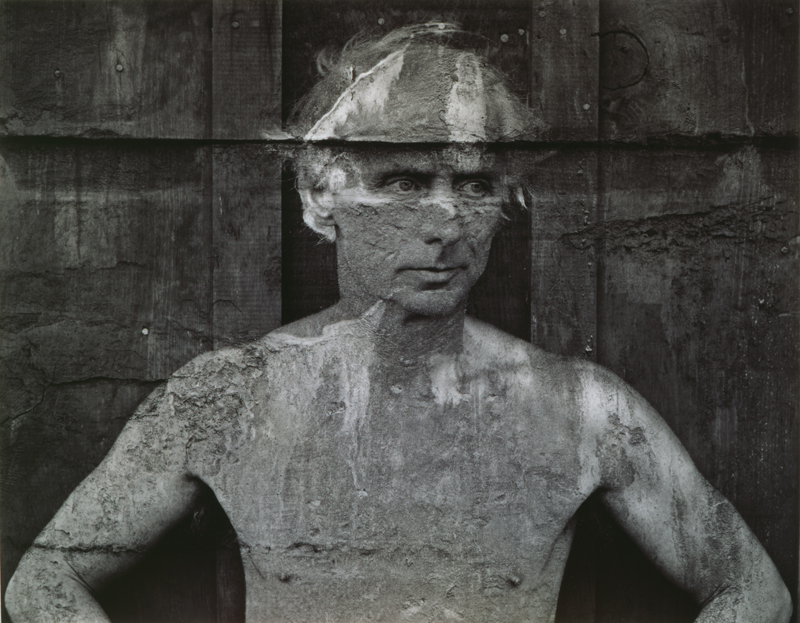

I found Frederick Sommer’s portrait of Max Ernst to be extremely compelling. Formed by overlaying the negatives of the portrait of the artist and a photograph of a concrete wall, the composite result displays a confusion of perspective that plays very interestingly with shallowness and depth and creates a disjunction through the union of the two images. At the same time as the photograph emphasizes depth, texture, and a sort of tactile three-dimensionality, it accomplishes this by mapping a human figure onto a wall, by portraying the originally three-dimensional Ernst in the mostly two-dimensional wall. The photograph confuses notions of superficiality and depth, the animate and inanimate, reality and surreality.

The surrealism of this photograph comes from these contrasts, or disjunctions, that exist within the image. At first, it seemed as though the image of Ernst was painted onto the wall, with the textures and patterns in the material appearing as brushstrokes. But as I looked more closely, it became clear that these textures extended beyond the figure of Ernst; they were the worn and corroded grooves and scrapes in the wall itself. Ernst is simultaneously embedded in the wall and stands apart from it. One could read here a comment on the distinction, or lack thereof, between art and life, and whether or not a human subject captured by the camera remains somehow animate, or if the distinction between lifeless and living objects becomes ultimately blurred through the medium of photography. The combination of the two images, the confusion of the animate and the inanimate, a human figure expressed only in the flat plane of a wall, produces a distinctly disjunctive, surrealist photograph that is striking and somewhat unsettling.

Image details:

Frederick Sommer (American, 1905–1999)

Max Ernst, 1946, 1946

gelatin silver print

Museum Purchase, Gridley W. Tarbell II Fund 1997.4

© Frederick & Frances Sommer Foundation