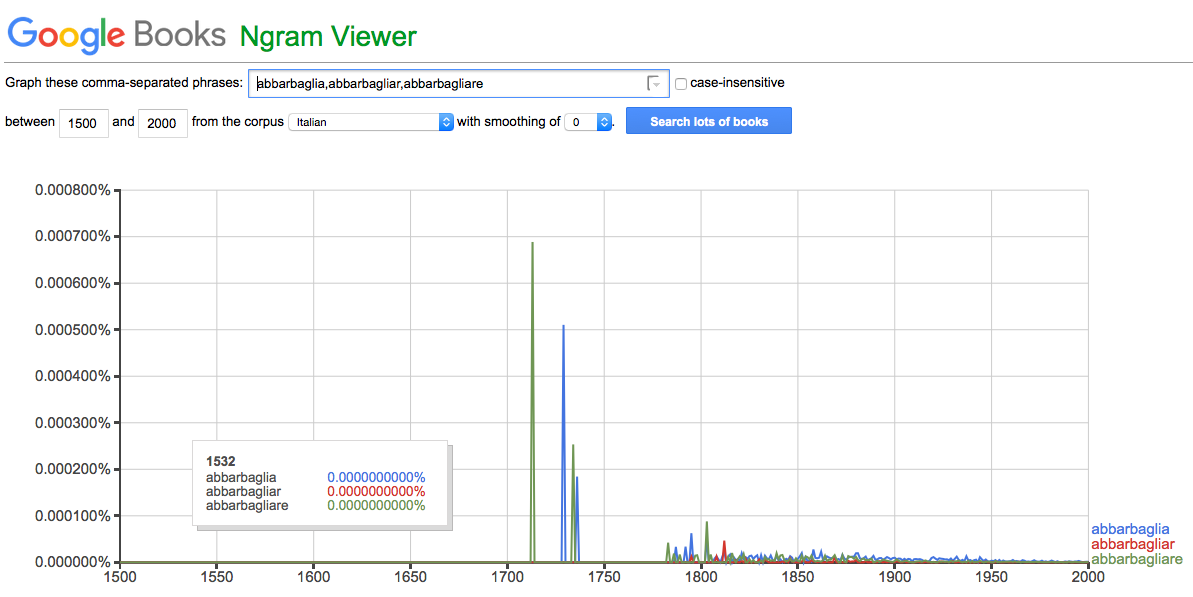

As I have mentioned elsewhere, the discovery of the abbarbagliar hapax legomenon was a turning point in my computational approach to Galileo’s text. This is absolutely a poetic term that would seem to have its Italian literary roots in Dante’s Paradiso (26.20) and later Petrarch’s Canzoniere (51.2). In opposition to the humbling awe implied by these two poets, Ariosto’s use of the term casts a particularly negative, anti-chivalric, or suspicious valence over the object or action that stuns the vision of the viewer. In order to understand whether this was indeed a novel usage of the term, one that would have stood out to Galileo’s readers with the connotations from the Furioso, I have been looking for more context. Given the many challenges with the Google Ngram Viewer, with the added complication of coverage of non-English sources, it wasn’t surprising to see these results:

Google Ngram Viewer search for variants of abbarbagliare in Italian texts. Accessed July 22, 2016.

For thoroughness, this needs to be compared with HathiTrust and perhaps even EEBO, which does offer a few texts in Italian. In order to hopefully develop a more representative corpus of Italian literature in this period for the work on computational parallax and Galileo’s library I have been using about 400 sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian texts that represent a range of genres. Variants of the verb abbarbagliare only appear in poetry in this corpus, and in poetry that seems to trace a lineage through Ariosto, not Tasso. In an article in preparation, I argue that this literary genealogy of disrupted vision needs to be understood in the context of cultural reactions to uncertainty.