One of the manuscripts that lists books found locked under the stairs at the home of Galileo’s daughter-in-law says: “Flora di Margherita Costa 4.”1 Costa, a Roman playwright who was very active in Florence at the end of Galileo’s lifetime, actually wrote two versions of a work called Flora feconda, or “Fertile Flora” to allegorize pregnancies of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany Vittoria della Rovere. Both were published in 1640, both by the Florentine press of Massi and Landi, so they do not disrupt the understanding of the geography or chronology represented by Galileo’s library. Instead, this title creates interpretative problems for textual and network studies of the library: the first version was an epic poem dedicated to the Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici, the second version was a play dedicated to the Grand Duchess.

Title page of Costa’s epic poem. Image by Crystal Hall.

Title page of Costa’s play. Scan available from the Bibliotheque nationale de France Gallica portal (http://gallica.bnf.fr/?lang=EN).

In nearly every way the two works are the same when read for literary characteristics, but in every way the texts themselves are different when examined computationally: 10 canti vs. 5 acts; 33,500 words vs. 22,500; hendecasyllables vs. heptameters; verse octaves vs. lyric speaking parts. The two works do have a similar vocabulary density, and yet the longest section of matching text is the 13-word prophecy that the protagonists will eventually give birth: “Da Quercia d’oro sorgerà gran Prole, / Che stenderà l’impero a par del Sole” (From a golden oak will rise a great heir / Who will extend the empire equal to the Sun’s).2

Works like Flora feconda and several others in Galileo’s library continue to challenge the ways in which digital humanities tools can accommodate the need to see multiple possibilities simultaneously and also to find the greatest common denominator shared by multiple books, in this case textual isotopes. As far as the two texts are concerned, treating them as witnesses, as manuscript scholars might, emphasizes change. I am keenly interested in the commonalities. What is the most we can say about both versions of Flora feconda? Answering that question will provide the method for distilling to common characteristics the isotopes of other books in the library and will likely reduce the noise in subsequent analysis.

Women in the Metadata, Texts, and Networks

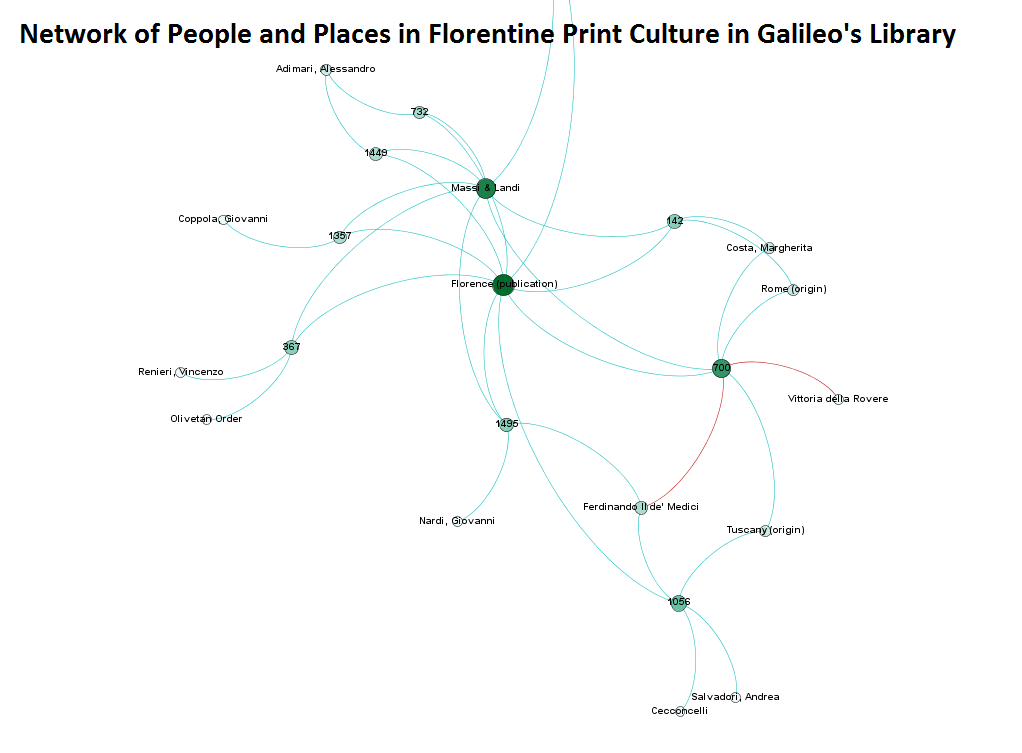

For Vittoria della Rovere, the dedicatee of the second version of the text, this flexibility of representing the data is critical to her visibility in Galileo’s library. Could she be present as a patron in the network of print culture represented by the collection? Building on the idea of addressing archival silence outlined by Lauren Klein, my approach to the network of people and places represented by the books in the library is slowly trying to account for known, but data-silent, figures of the intellectual community represented by the library, using Florence as a prototype.3 Ferdinando II appeared elsewhere as a dedicatee in the collection, but without taking into consideration the isotope of Flora feconda that is dedicated to della Rovere, she would be absent so far from the network, even though she was a known patron of writers and artists, she was wife to the Medici Grand Duke (himself protector of Galileo), and the very figure for whom the allegory of Flora was written. The network graph in Figure 6 is an attempt to visualize that possibility.

Detail of a Gephi network graph of the relationships represented by the proper nouns that appear in the paratexts of books printed in Florence in Galileo’s library. Node size and color correspond to degree. Edges are partitioned by certainty (blue) and uncertainty (red). Books are labeled by unique ID instead of title. Choosing to include either Ferdinando II or Vittoria in the graph does not accurately represent the information at hand, nor does it allow for a chance to consider more connections.

[1] Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Ms. Gal. 308, f. 168, line 22.

[2] Margherita Costa, Flora feconda poema (Florence: Massi and Landi, 1640) V.41.7-8; Flora feconda drama (Florence: Massi and Landi, 1640) III.iii, p. 85. Print.

[3] Lauren Klein, “The Image of Absence: Archival Silence, Data Visualization, and James Hemmings,” American Literature 85.4 (2014): 661-688. Web.