In the novel, Austen does not seem to accept gossip as frivolous; indeed, she defends it by making it useful and even central to her novels. As Erin M. Goss writes, “Austen’s turn to this oft-derided speech act seems designed – much like her turn to novels in Northanger Abby (1818) – to defend it against the derogation, so often lodged at novels as well, of its uselessness, frivolity, and potential for harm,” (Goss, 170). In making gossip such a central aspect of Emma, Austen legitimizes it as a form of social connection. She does not mock it or belittle it, but instead portrays it as necessary and interesting. Gossip is not only part of the plot of Emma; it lays the foundation for the plot. Emma’s personal growth is rooted in her own mistakes. Time and time again, she meddles where she shouldn’t and tries to form attachments where none exist. These mistakes could not exist without gossip, and neither could Emma’s own growth. For example, in attempting to match Harriet Smith with Mr. Elton, Emma attempts to discuss Harriet’s health with him, to which he responds poorly. Emma’s personal growth is only possible because of gossip.

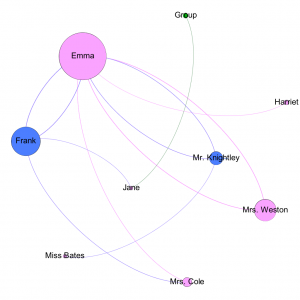

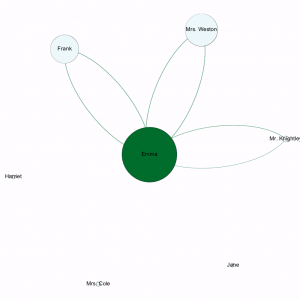

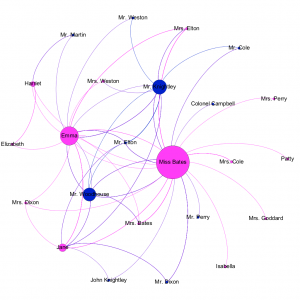

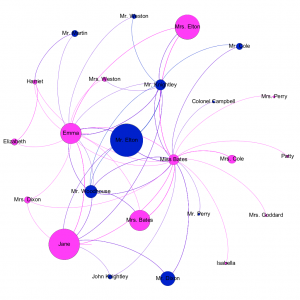

In these graphs, we see the women of Emma take center stage and dominate the social scene. Although the men are objects of interest, they are not generally gossips. In this way, these graphs allow us to see how women dominate the interactions of Emma from a data-driven perspective. This trend is evident in the “Full Novel, About” graph, in which women dominate the gossip, while men are more equally gossiped about. Consider Miss Bates’s node in “Chapter 3, About,” as she gossips about far more people than anyone else. Here, we see one example of a relatively poor woman using her ability to gossip to her advantage, and we see this phenomenon confirmed graphically. Additionally, consider how Frank Churchill uses this network of gossip to his advantage in “Chapter 8, About.” He mimics all of Emma’s theories, using the gossip around Jane’s pianoforte and Emma’s propensity for speculation to his advantage. Not only do we see how women make use of this social capital to elevate their own importance, but we also see how men might use this network strategically to their advantage.

This project has addressed, and, in some ways, confirmed the literature surrounding the question of gossip as social capital in Emma. In a patriarchal society, Austen’s female characters use gossip as a way to amplify their own voices and maintain some form of power. Knowledge provides a certain amount of social currency in the world of the novels. In a society where sources of entertainment were limited and women were barred from most forms of work, gossip becomes a common pastime, and having access to information gives the gossiper some power. Austen elevates female voices through the use of gossip, and we may look to this graphical evidence for a greater understanding of how she does so.