by Walter Wuthmann ’14.

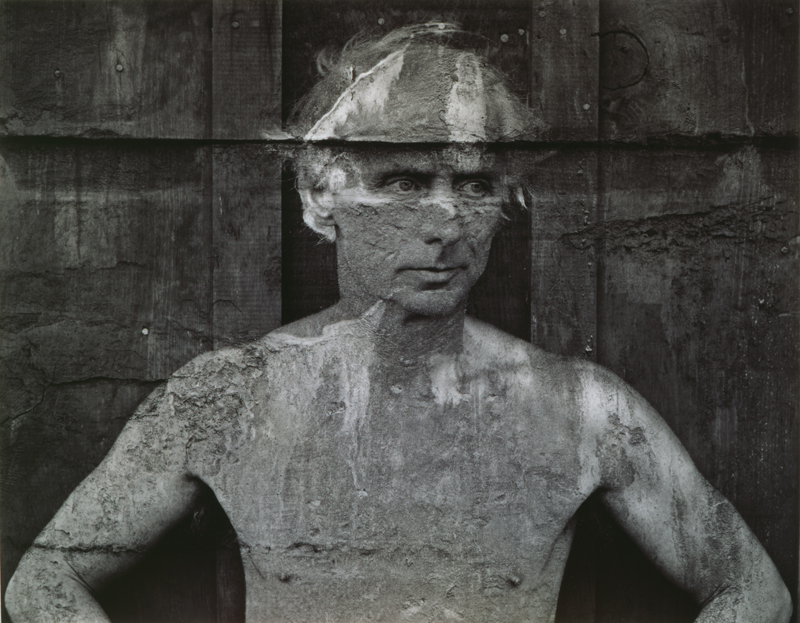

At first glance, Frederick Sommer’s photograph, Max Ernst, 1946, looks like an incredibly well-painted mural. Some of the body is wearing away; white streaks carry his skin down the wall like rain damage; the roughness of the wall bubbles up through his skin, implying time and weather and wear. His eyes remain untouched, piercing from the center of the composition, looking out across some unknown battlefield, his brow accentuated by a groove in the wall, seemingly furrowed in deep thought. The impression given is that this fading, yet still affecting, mural is of someone of importance, some revolutionary or political leader.

This is not actually a mural: it is two photographs layered together by Frederick Sommer; the subject is a surrealist artist, Max Ernst. Sommer tricked us into these grand thoughts about Ernst, inspiring reverence of his weathered body and piercing gaze. Sommer was able to use the technical manipulation of photography to push the surrealist agenda – an agenda that stresses the importance of revolutionizing life, and not just art.

Sommer created an image that is more than the sum of its parts. By combining a portrait with the image of a corroding wall, Sommer generated cultural and political associations that didn’t exist with either image in isolation. He elevates the surrealist artist to the level of revolutionary/martyr/hero – the kind of man who deserves to be memorialized on a decaying wall. He combines two real images to create one that does not exist in reality. Using this surrealist technique, Sommer highlights the cultural importance of surrealism in this stirring image of one of its practitioners.