Montparnasse, Paris on a chilly winter afternoon

Montparnasse, Paris on a chilly winter afternoon

Murder can be elegant, but only if it takes place in foreign lands. The most effective literature in this realm evokes a sense of place that is as central as the narrative or characters. This is the premise that guides my reading of murder mysteries and modern detective novels. French bookstores, packed with paperback translations of the latest Michael Connelly and Harlan Coben, are adhering to this rule, so I do not entirely fault them. The term roman noir is French, but I have yet to discover a French crime novel that is darker than grey, perhaps because French writers are too sensitive to “la tendre indifférence du monde” (“the tender indifference of the world,” as Camus put it in The Stranger).

I find it difficult to distinguish between bande dessinée (BD) and roman graphique, although there is no question that Camus’ Stranger in graphical form, drawn by Jacques Ferrandez, is the ultimate graphical crime novel. Bande dessinée might be called comics in English, but they have long progressed beyond the petty crimes in TinTin and Milou to Blacksad, a noir-ish cat who is a private eye (yes, you read that right) with all the requisite characteristics of le détective de choc – he is sad, solitary and disillusioned. Pierre Taranzano progresses beyond death, in his thought-provoking Les Thanatonautes series.

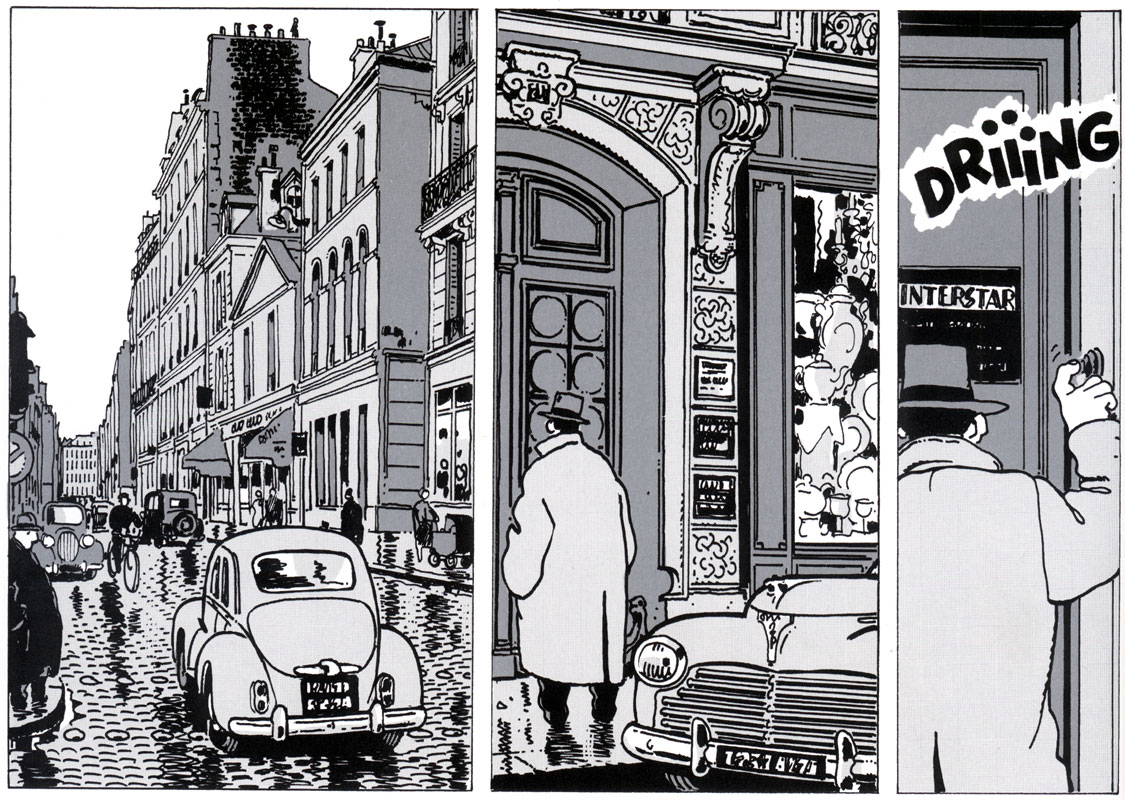

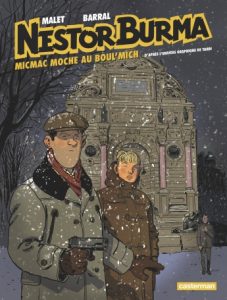

Nestor Burma, by Jacques Tardi, is a former anarchist, who now foils crimes authentically located in the different districts of Paris. My favourite Tardi is Mic-Mac Moche au Boul’ Mich’, not just because of the alliteration, but because I bought a copy in a Parisian BD store on the Boul’ Mich’ at 10 a.m., on a weekday, and had to push my way through the crowd of adults lounging against the bookshelves reading the latest issue. (Note to self: check the data on productivity in the French economy.)

Nestor Burma, by Jacques Tardi, is a former anarchist, who now foils crimes authentically located in the different districts of Paris. My favourite Tardi is Mic-Mac Moche au Boul’ Mich’, not just because of the alliteration, but because I bought a copy in a Parisian BD store on the Boul’ Mich’ at 10 a.m., on a weekday, and had to push my way through the crowd of adults lounging against the bookshelves reading the latest issue. (Note to self: check the data on productivity in the French economy.)

And speaking of exotic places, why did I never think of writing my thesis on the “imperial cultural hegemony of African Francophone Bandes Dessinées”? The author of The Paris Enigma is not a Frenchman, but Pablo de Santis of Argentina. The denouement of this original and entertaining story occurs on the newly-erected Eiffel Tower, where twelve of the world’s greatest detectives convene during the Paris World’s Fair of 1889, to resolve the murder of one of their own group. However, the finest Argentine writers seem incapable of eluding the influence of the masterful Jorge Luis Borges, even in the realm of murder mysteries.

It’s a real crime to demolish a stunning building like La Samaritaine

It’s a real crime to demolish a stunning building like La Samaritaine

What do you get when you add a PhD in Mathematics to a lucid literary style? The answer is Guillermo Martínez, whose Oxford Murders improbably links references to Heisenberg’s principle and Gödel’s theorem. Other worthwhile contributors to the genre include Arturo Perez Riverte, Mempo Giardinelli, Ricardo Piglia and Jose Pablo Feinmann. The Buenos Aires Quintet by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (from Barcelona) features Pepe Carvalho, who has been described as a “metaphysical gumshoe;” on a more physical note, Carvalho loves dinner and women, and (even more) dining with loving women.

Montalbán was the likely inspiration for Italy’s most popular police commissioner, Salvo Montalbano, but Camilleri’s books would be vastly less appealing if the setting were anywhere else beyond Sicily. The inspector is as flawed and idiosyncratic as that island, and both manage to be attractive and appalling in equal measure—or maybe the balance tips toward appalling. My favourite Italian mystery writer, Umberto Eco, probably appeals to me because he is more akin to the Borges-Argentine school than Camilleri. So it is not surprising that his novel, The Prague Cemetery, hurtled to the top of the bestseller list in Argentina. Eco is a professor of semiotics and this is reflected in his writing; but his erudite, effervescent and illuminating Name of the Rose is to the Da Vinci Code as Champagne is to a flat Coke. (Or, as he modestly puts it, his work levies “a tax on idiocy.”)

Japanese fiction includes a number of wonderful off-beat productions that might be classified in this fiscal-IQ genre, such as Kobe Abe’s Ruined Map and Murakami’s Wild Sheep Chase. The canon of crime writers in Japan is Seicho Matsumoto, whose Inspector Imanishi projects the tact and courteous deference that typify Japanese interactions even when confronting callous criminals. By way of contrast, as one of my friends in Tokyo points out, Natsuo Kirino is unusual in Japanese society because she is “outspoken and strong-willed.” Even a non-Japanese reader might find Kirino’s Grotesque to be unsettling and disturbing. The narrative is related from the point of view of a sociopath, and this excursion across such an alien mental landscape tainted my thoughts for days after. Fortunately, alienist insights like those of Kirino and Mishima offer round-trip tickets into other worlds, where we are always safely ensconced and moored in our own reality; we can be captivated but not captured.

Scandinavian mystery writers were long a mystery to the American reading public, but no longer, after the Millenium. Stieg Larsson’s trilogy about the girl with the dragon tattoo hacked away at our aversion to literature in translation. Now every Kindle is loaded with the enthralling, appallingly-noir police procedurals that only a midnight sun can inspire. Don’t make the mistake of believing that The Laughing Policeman by Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo is lighthearted fiction. Kurt Wallander (by Henning Mankell), Erlunder (Arnaldur Indriðason of Iceland where, like Madonna, everybody is known by their first name), and Harry Hole (Jo Nesbo) lead such fractured lives that the murders they investigate appear to be a natural extension of the world they inhabit. Divorced alcoholics past their sell-by date, in uncertain health and equally uncertain unhealthy relationships with estranged offspring and the occasional romantic partner, these characters are nonetheless mesmerizing.

And, of course, academia is the most hazardous terrain where, according to James Hynes, even the eminently deserving might Publish and Perish. If one considers the number of heinous (literary) crimes committed in Oxford, surely the population of Dons must be now on the verge of extinction…