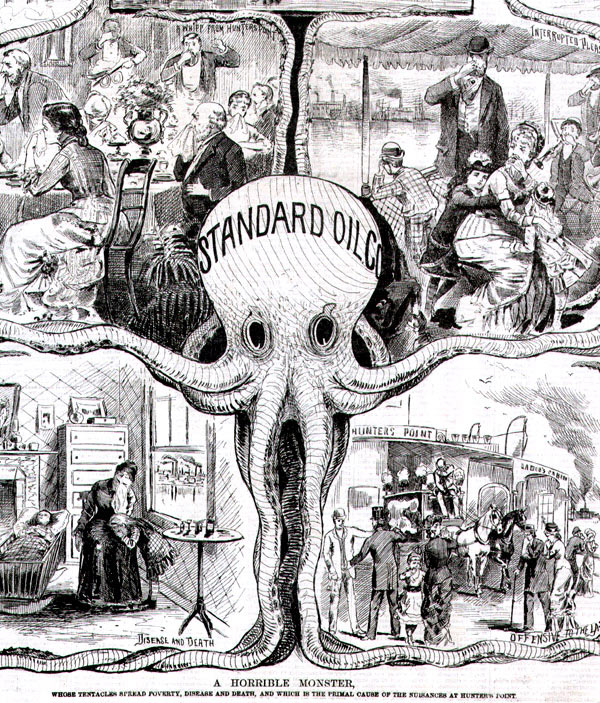

The breakup of Standard Oil Company in 1911 continues to be wielded as a bludgeon to threaten successful firms, and as a banner to encourage populists in their forays against free markets. Consider the recent Executive Order on Competition: “When past presidents faced similar threats from growing corporate power, they took bold action. In the early 1900s, Teddy Roosevelt’s Administration broke up the trusts controlling the economy—Standard Oil, J.P. Morgan’s railroads, and others—giving the little guy a fighting chance.”

The breakup of Standard Oil Company in 1911 continues to be wielded as a bludgeon to threaten successful firms, and as a banner to encourage populists in their forays against free markets. Consider the recent Executive Order on Competition: “When past presidents faced similar threats from growing corporate power, they took bold action. In the early 1900s, Teddy Roosevelt’s Administration broke up the trusts controlling the economy—Standard Oil, J.P. Morgan’s railroads, and others—giving the little guy a fighting chance.”

In 2000, when District Judge Jackson ordered the break-up of Microsoft, he compared the company to Standard Oil: “Mr. Rockefeller had fee simple control over his oil. I don’t really see a distinction.” Today, of course, who cares about Microsoft’s monopoly power?

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF STANDARD OIL

What does economic analysis have to say about the role of Standard Oil (SO)? My superpower is speed-reading, and an examination of thousands of antitrust cases empirically confirms the suspicion that antitrust is typically motivated by politics and populism more than economics. Most of these lawsuits can be lodged under the title of United States v. Laissez Faire Inc (yes, this is a real antitrust case, not a satirical reference).

MARKET SHARE

All antitrust indictments start with an assessment of market share. At the same time, the relevant market comprises one of the most imprecise and malleable concepts imaginable (to the satisfaction of consultants on both sides). Standard’s share of refining had been falling for over a decade. There were over 100 domestic oil‑refining firms in the national market, with many new entrants in the Southwest, along with other large competitors like Texaco, Gulf Oil, and Sun.

However, the relevant market was global, rather than domestic, and the majority of SO transactions were overseas. The company’s international competitors included firms from Canada, Peru, Britain, Poland, India and Russian. SO’s market share in 1909 was just 14 % of the global market.

OUTPUT AND PRICES

At the time Standard Oil was founded in 1870, the price of kerosene was 30 cents a gallon. Two decades later, the price had fallen to around 6 cents a gallon. Kerosene output had correspondingly expanded enormously (contrary to the “standard” monopoly model). SO was able to take advantage of economies of scale, quantity discounts, and operating efficiencies to reduce costs and prices. The beneficiaries were the “little guy” that the Executive Order is allegedly protecting.

PREDATORY PRICING?

“Predatory” pricing is one of those empty weasel words which evoke emotional responses rather than representing valid economic reasoning. Lower prices benefit consumers, period. Charges of predatory pricing are usually brought by losers in the marketplace; but, as the court stated in Arco v. USA Petroleum, “cutting prices to increase business is often the essence of competition.”

The FTC seems bent on resuscitating this concept against Amazon, in a move that might be termed zombie economics. The nonsensical nature of predatory pricing is revealed in such examples as an antitrust ruling that forced Walmart to increase consumer prices in Germany.

SUBSTITUTES

A prerequisite for monopoly is a lack of available substitutes. SO’s major market was kerosene, which was used for stoves and lighting. Stoves could also be fuelled with coal, wood, corn waste, and other products. Alternatives to kerosene lamps included candles, whale oil, and camphine (a volatile fuel consisting of turpentine and alcohol). Later, with the development of electricity, yet another substitute was developed, but kerosene remained viable owing to its relatively cheap and ready access. In fact, the market for electric automobiles failed to develop further at that time because gasoline was far more cost-effective.

SIDE DEALS AND SUBTERFUGE

The government case passionately declared that SO was bent on “oppressing the public and destroying the just rights of others, … its infinite potency for harm and the dangerous example which its continued existence affords, is an open and enduring menace to all freedom of trade, and is a byword and reproach to modern economic methods.”

From a less breathlessly-partisan perspective, SO was able to use its countervailing power as leverage against other oligopolies to obtain rebates and other privileged deals, that translated into benefits to consumers.

THE NEW MUCKRAKERS

The greatest misstep of Standard Oil was in not recognizing the power of bad press. Ida Tarbell, whose personal animus against the firm was founded in her father’s failure in the oil industry, provided the supposedly objective analysis that would justify using the power of the federal government to disrupt and destroy a successful private enterprise. One of today’s Ida Tarbells, equally unqualified in Economics, has been elevated as head of the FTC. Just as before, these new muckrakers are mis/using empirically unwarranted concepts like predatory pricing to justify politically-motivated policies against “Big Tech.” As Frederick Scherer pointed out, “it is questionable whether the circle of [antitrust] beneficiaries extends much wider than the attorneys who earn sizeable fees interpreting its complex provisions.” History shows that these measures are unlikely to benefit “the little guy.”

EPILOGUE

The tentacles of the alleged SO octopus regenerated after the dissolution of the company. These enterprises became larger than ever, proof of the underlying valid economic reasons for their size and dominance. The new entities included:

Standard Oil of New Jersey (EXXON)

Standard Oil Company of New York (MOBIL)

Standard Oil of California (SOCAL)

GULF Oil Company

Texas Company (TEXACO)

Esso (SO)

Exxon and Mobil merged in 1999, appearing as number 3 (number 10 today) on the Fortune 500 list, a ranking that is “synonymous with business success.”