Can you name a French woman inventor? Marie Curie often tops many popular lists of soi-disant French women inventors, even though she was not an inventor, but a scientist (and Polish to boot). According to Voltaire, (whose mistress, Mme du Chatelet, was an exceptionally accomplished scientific thinker) learned women certainly existed, but it was quite impossible to find any women inventors. Another writer, Antoine de Neuville, proclaimed that the inventive activity of French women tended to be limited to corsets, and not much else. In this, such commentators were being as obtuse as Voltaire’s fictional hero, Candide.

Several of Voltaire’s contemporaries provide intriguing examples of inventive and entrepreneurial abilities, especially in the medical field. Marie Marguerite Bihéron (1719-1795) was a gifted anatomist and surgical practitioner. She disguised herself in male attire to attend classes in anatomy and dissection, and illegally acquired bodies from the military for her autopsies.

Work of this sort was hampered by the lack of refrigeration and rapid decomposition of the bodies. Bihéron formulated a malleable and extremely durable wax-based material that was even resistant to flame. She was said to have represented nature “with a precision and truth which no person has yet achieved.” Her detailed and extensive medical knowledge, and meticulous reproduction of the human body, led to her becoming a preeminent authority on the creation of lifelike anatomical models. Bihéron sold these coveted models to such illustrious clients as the King of Denmark and the Empress of Russia for use in their national scientific academies. She kept her method secret, but daily admitted paying visitors to her workshop to view the displayed models, and further participated in national exhibitions. She was invited to make several presentations to the Academie Royale des Sciences, and acquired an international reputation as an innovative maker of accurate anatomical models.

Marguerite du Coudray (c. 1714–94), a midwife, secured royal patents in 1759 and 1767 for her “machine” or anatomically correct doll to teach obstetric methods. In May 1756 the prestigious all-male Academy of Surgery examined her invention and formally acknowledged their approval. She was adept at securing patronage, and also obtained a royal grant to travel the countryside to educate and train rural midwives.

Marie Gillain Boivin (1773–1841) was married at 24, and widowed by 25. She was formally trained as a midwife, but acquired a thorough background in gynaecological surgery through theoretical investigations and extensive practice, as well as empirical analyses of the overall population of cases she and others encountered. Boivin was fluent in Greek, Latin, English, and Italian, and closely followed medical developments in other countries. Her books, such as The Art of Obstetrics (1812), were widely cited and included in medical libraries around the world. Anyone who reads these works cannot fail to be impressed by her brilliant mind and extensive in-depth knowledge. She was commended by eminent surgeons, including the members of the Royal Society of Medicine in Bordeaux, and the University of Marburg in Germany which granted her an honorary medical degree in 1827. In 1894, the Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin noted that some of her work was “still worth reading.” Marie Boivin’s innovations included surgical methods to excise cancerous growths, and she also devised medical instruments such as an improved pelvimeter and a vaginal speculum for examining the cervix.

Marie Gillain Boivin (1773–1841) was married at 24, and widowed by 25. She was formally trained as a midwife, but acquired a thorough background in gynaecological surgery through theoretical investigations and extensive practice, as well as empirical analyses of the overall population of cases she and others encountered. Boivin was fluent in Greek, Latin, English, and Italian, and closely followed medical developments in other countries. Her books, such as The Art of Obstetrics (1812), were widely cited and included in medical libraries around the world. Anyone who reads these works cannot fail to be impressed by her brilliant mind and extensive in-depth knowledge. She was commended by eminent surgeons, including the members of the Royal Society of Medicine in Bordeaux, and the University of Marburg in Germany which granted her an honorary medical degree in 1827. In 1894, the Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin noted that some of her work was “still worth reading.” Marie Boivin’s innovations included surgical methods to excise cancerous growths, and she also devised medical instruments such as an improved pelvimeter and a vaginal speculum for examining the cervix.

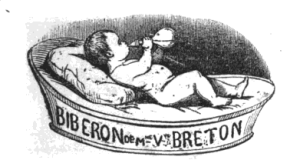

Yet another midwife, Marie-Magdeleine Breton, obtained patents in 1824 and 1826 for a baby’s feeding bottle and artificial nipples, for which she sought and obtained favourable notice from pharmacists at the Royal Academy of Medicine. Breton was adept at promotion and commercialization. A firm was established to manufacture and market her products, and she won numerous medals at national Expositions in 1827, 1834, 1839 et 1844. She distributed a free handbook offering advice for mothers, Avis aux mères qui ne peuvent pas nourrir, ou Instruction pratique sur l’allaitement artificiel, that included testimonials from the Minister of Commerce, and signed each copy to prevent counterfeiting. Realizing that the high prices she charged for her innovations limited the market, she practised price discrimination, offering different versions of the product at lower prices.

The modern French patent system was introduced in 1791, and in the first century almost 8,000 inventions featured women as the patentee or agent, amounting to just under two percent of the total. The patterns signal growing sophistication over time among women at both invention and innovation. The fraction of patents to women in noncommercial occupations such as midwives or teachers fell from 43.2 percent before 1835, to 13.4 percent after 1850. During this early industrial era, women were increasingly contributing to technologies in the “new economy” of their day. Female patents were much more likely to deal with manufacturing, which increased over time to almost two-thirds of all filings.

The first woman to be granted a patent in 1791, Françoise de Jaucourt, obtained protection for a novel type of varnish. She managed her own property independently of her husband, and was filing as the assignee of her business partner, Julienne de la Richardais. De la Richardais belonged to a military family, and in the 1770s had created the varnish to protect materials like leather and metals and guns from corrosion. The fact that the partners were still interested in paying the high patent fees several years later suggests this was a profitable invention.

Women’s patented inventions ranged widely in subject matter, from the exotic to the mundane. Jeanne Genevieve Garnerin (1775–1847) was the first woman to descend in a parachute from a balloon. In 1802, she and her husband, André-Jacques Garnerin visited London to give exhibitions of balloon flight. At the same time, she filed a patent application for “a device called a parachute, intended to slow the fall of the basket after the balloon bursts.”

Amélie de Dietrich (1776–1855), a “maîtresse de forge” from a wealthy aristocratic family, was the owner of five patents for iron railroads and bridges, that most likely covered inventions created by her workers. After her husband died in 1806, she completely reorganized the family firm, now called Veuve (widow) de Dietrich & Fils, and also acquired neighbouring factories. Mme de Dietrich expanded the product line to metal goods and household appliances such as stoves, and is credited with the introduction of decorative designs in industrial products. At the time of her death, she left to her sons one of the most prominent enterprises in the region, that would continue to flourish for another two centuries, and today is one of the oldest firms in France.

Women were also experienced in the bookmaking industry, and this is reflected in the patent records. Eugénie Niboyet (1796-1883), the grand-daughter of physicist Lesage, and a writer who was a notable figure in the struggle for women’s rights, obtained an 1838 patent for indelible printing ink. Eulalie Lebel (1809-1898) was the only daughter of the printer Jacques-Auguste Lebel, and after her husband abandoned his family she founded her own printing firm. Between 1849 and 1855, Mme Bouasse-Lebel and her son obtained four patents related to printmaking. Maison Bouasse-Lebel frequently entered their products at expositions, and received domestic and international accolades.

Patentees of items that were controlled by the French government, such as printing presses and firearms, had to be especially adept at maintaining quality and negotiating with state bureaucrats. The Gévelot company manufactured cartridges and fuses in their Paris location, and gunpowder at Issy, just outside the city. Joséphine Gévelot partnered with François Lemaire, a businessman, to obtain a patent for firearm cartridges in 1845. Her company was associated with eight more patents in the following decade, including one for an invention from Italy. At the Paris exhibition of 1844, the jury awarded a bronze medal, noting that “Mme Veuve Gévelot has perfected the various details of manufacturing, and her products are always very much in demand in the market. The house of Gévelot produced well in 1839 [before her husband’s death]; it produces a great deal better in 1844.”

All champagne afficionados are familiar with the innovations of Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin (apparently you need to be of drinking age even to visit the website). Elisabeth Gervais deserves to be as celebrated for her research and development into oenology, which resulted in two patents in 1818 and 1820 for apparatuses to condense the vapours in winemaking. The Bordeaux Royal Academy gave a prize in 1822 to a researcher who allegedly disproved her findings; nevertheless, her method was adopted by winemakers and proved to be highly successful commercially. She opened one company in Paris to market the patent rights for specific districts, and a second in Montpellier that was under the management of her brother. Despite the academic quibbling among contemporary scientists about the originality and value of the invention, the sale of these rights to practicing winemakers earned her “considerable profits.”

Marguerite-Marie Degrand made valuable contributions to scientific and industrial advance, achieving success in the international quest to replicate crucible steel from Damascus. In 1819, Mme Degrand received an honourable mention for her stainless steel cutlery, and a medal in 1823 for her contributions to the art of making metal products that rivalled the quality of Damascus steel. The Society for the Encouragement of National Industry bestowed on her its Grand Medal, and she became one of its rare female members in 1824. Between 1830 and 1840, her workshop was one of the most eminent for the production of cutlery and steel goods like razors, items that are still highly prized by collectors today.

As might be expected, many inventions reflected women’s comparative advantage in household articles, apparel, and other consumer goods. The Parisian perfumer, Madame Delacour, whose establishment on Rue de la Monnaie was patronized by influential aristocrats, patented her celebrated “topique labial” lip balm that apparently included pomegranates, rose salve, and sweet almonds – as well as zinc sulphate. Mademoiselle Caroline Chevalier-Joly and a male coinventor filed an application to protect their new tooth powder. Mme Josse was known for concocting the most natural-looking vegetal rouge, and Mlle Martin served royal and aristocratic women her patented cosmetic confections in elegant porcelain jars from the Sevres factory.

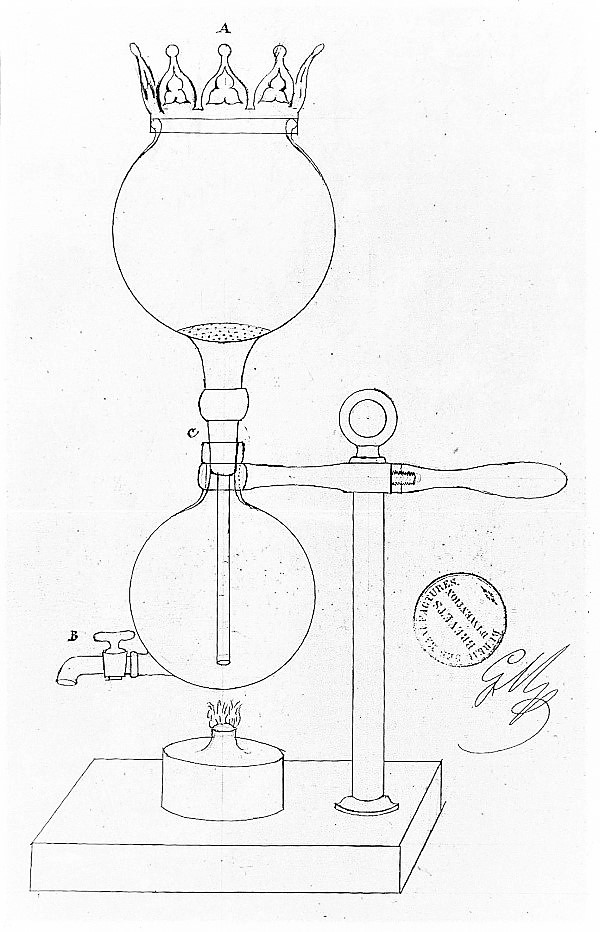

Household appliances attracted a great deal of attention, including the attempt to brew the perfect bol of coffee. Mme Rosa Martres belonged to a family of inventors, and she received seven patents for improvements in coffee-makers. Jeanne Richard filed a patent for another machine in 1837. Marie Fanny Vassieux of Lyons patented a vacuum coffee brewer that featured two glass spheres, with a spigot to serve the beverage. Her very successful coffeemaker design was still being used and adapted many decades after the expiration of her six patents, and likely was the inspiration for the American Silex coffeepot.

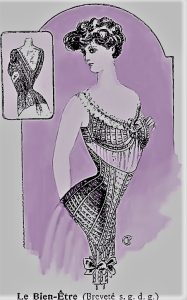

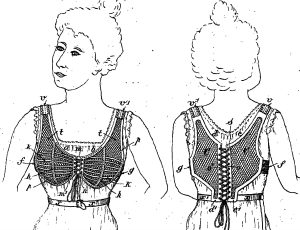

And, of course, de Neuville was not entirely incorrect – women did indeed patent dozens of corsets (as did male inventors). Adelaide Gaches-Bartelemy, a medical doctor, devised a “novel hygienic corset” which did not unduly compress the body, and even obtained patents in the United States for her invention. But the most celebrated corset invention was by Herminie Cadolle (1845–1926), the owner of an establishment making bespoke underwear, that still exists today. In 1889 she patented Le Bien-Être (“well-being”), essentially the first appearance of the modern bra. Improvements in corsets and underwear may not have earned their creators Nobel Prizes, but they undoubtedly increased the welfare of all women — including Marie Curie.

For additional reading, see:

B. Zorina Khan, “Invisible Women: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Family Firms in Nineteenth- Century France,” Journal of Economic History, vol. 76 (1) 2016: 163-195.

Abstract: The French economy has been criticized for a lack of integration of women in business and for the prevalence of inefficient family firms. A sample drawn from patent and exhibition records is used to examine the role of women in enterprise and invention in France. Middle-class women were extensively engaged in entrepreneurship and innovation, and the empirical analysis indicates that their commercial efforts were significantly enhanced by association with family firms. Such formerly invisible achievements suggest a more productive role for family-based enterprises, as a means of incorporating relatively disadvantaged groups into the market economy as managers and entrepreneurs.