I once set off the exit alarm at the Bowdoin Library. The staff scrutinized me with great suspicion when they discovered that the title of the volume in my hand was: To Steal a Book is an Elegant Offense. This phrase arguably mirrors ancient Confucian principles that persist in cultural attitudes today. The book (which, I hasten to add, I was NOT attempting to elegantly purloin) claims that China favoured open access to ideas because their unique culture values social rather than individualistic rights.

Botanical Buccaneers and Cultural Pirates

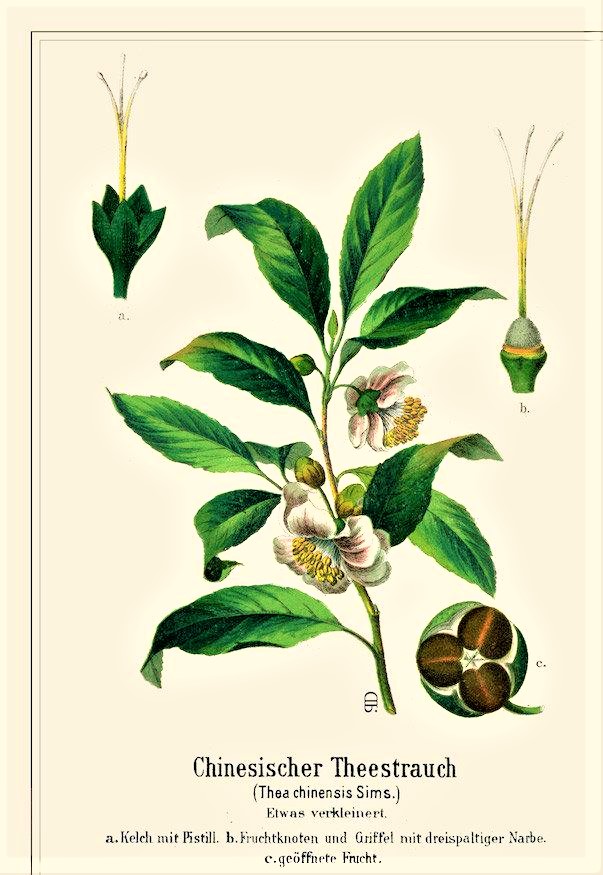

Explanations that appeal to “culture” are unsatisfactory, since cultures vary across place and time in a manner that needs to be explained itself – in other words, culture is not exogenous. European countries also were guilty of reprehensible ploys and (both literal and figurative) piratical policies when they were undergoing development. The global tea trade was boosted when the British “botanical buccaneer” Robert Fortune smuggled Camellia Sinensis specimens from China. Initially, China was the victim of industrial espionage by Europeans, who were bent on “borrowing” technical know-how and trade secrets about innovative Chinese papermaking, porcelain, dyes and textiles.

Explanations that appeal to “culture” are unsatisfactory, since cultures vary across place and time in a manner that needs to be explained itself – in other words, culture is not exogenous. European countries also were guilty of reprehensible ploys and (both literal and figurative) piratical policies when they were undergoing development. The global tea trade was boosted when the British “botanical buccaneer” Robert Fortune smuggled Camellia Sinensis specimens from China. Initially, China was the victim of industrial espionage by Europeans, who were bent on “borrowing” technical know-how and trade secrets about innovative Chinese papermaking, porcelain, dyes and textiles.

Chinoiserie became the rage after the European East India Companies initiated commercial exchanges with the Chinese empire in the 17th century. Chinese styles and cultural goods could be detected in fans, fashion, furniture and other forms of art and artifacts. Discerning visitors to the Royal Pavilion at Brighton consider the architecture and interior design to be chinoiserie gone raving mad (to put it tactfully). Works such as the 1871 On the Study and Value of Chinese Botanical Works, by a doctor working at the Russian embassy in Peking, directly copied the original. In France, Voltaire’s L’Orphelin de la Chine (The Orphan of China) similarly paid “homage” to The Orphan of Zhao, by a thirteenth-century Chinese playwright.

‘First reading in 1755 of Voltaire’s L’Orphelin de la Chine…’ by Charles Lemonnier

Copyright Piracy, Once Upon a Time in America

Europeans were once quite certain that Americans would never progress beyond blind copying of British and French culture. Take for instance, The Edinburgh Review in 1820, which contemptuously concluded that Americans “have done absolutely nothing for the Sciences, for the Arts, for Literature, or even for … Political Economy.” They wondered, “In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book? or goes to an American play? Or looks at an American picture or statue?” That was a quite unbiased assessment of American culture at that time, which I myself share (apart from the jab about Economics). In G H Putnam’s view, “an international copyright is the first step towards that long-awaited-for `great American novel’.”

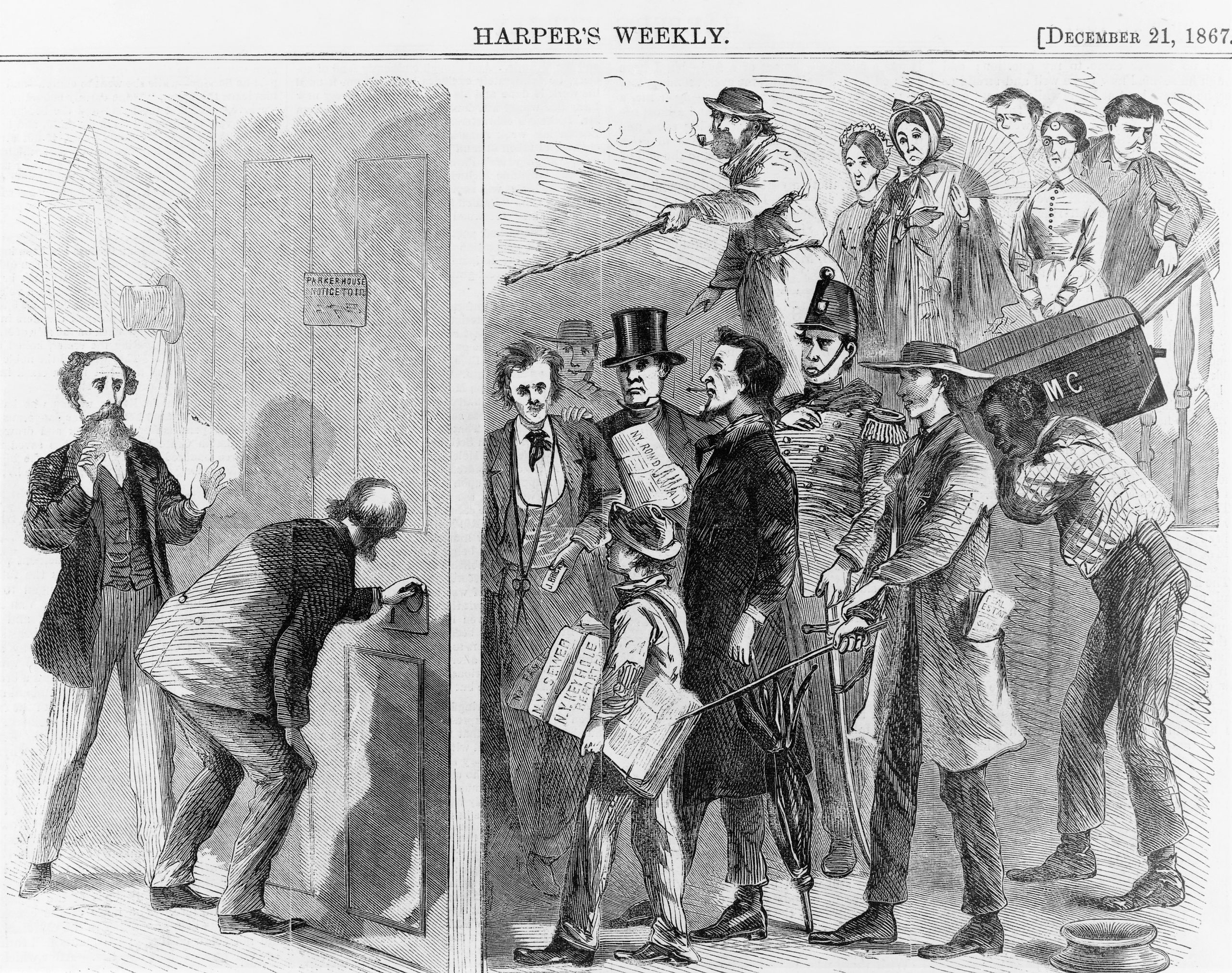

For over a century, Americans insouciantly shrugged off global denunciation and refused to acknowledge international copyright laws. Charles Dickens gloomily wrote in 1842: “I have no hope, whatever, of stopping American Piracy in this Generation.” And indeed, it was not until 50 years later that the United States would retire from its buccaneering ways, and engage in copyright reforms. International Copyright petitions were submitted on more than 100 occasions in the Congressional sessions through 1875. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Longfellow’s alma mater Bowdoin College, and representatives of the citizens of Portland, Maine all lobbied long and heatedly for stronger copyrights.

Harper’s Weekly cartoon in 1867 showing Charles Dickens hiding from a mob of Americans (all characters from his own novel) whom he had denounced for their copyright piracy.

However, towards the end of the nineteenth century, the U.S. began to produce cultural goods worth protecting, so the “balance of the ledger” shifted. In 1891 the Chace International Copyright Act finally granted protection to works of selected foreign citizens. Even then, U.S. copyright rules remained among the weakest in the world, balancing the rights of authors with those of the public. Copyright primarily protects the narrow rights of publishers and others who wish to control access to different forms of expression. Piracy benefited developing countries like the United States at that time, by increasing public access and promoting learning and social welfare.

Copycats and Copyrights in China

Just as Americans were once reviled, China has been widely criticized for Shanzhai, or its “copycat culture.” A depressing array of news items and popular opinions argue that Chinese society inherently lacks creativity and can do no better than slavishly copy Western cultural discoveries. The international version of the New York Times in 2012 even pondered the question “Why Do the Chinese Copy So Much?” These allegations are far off the mark, as China is now one of the world leaders in creativity, and one of the strongest enforcers of domestic copyrights.

The Chinese attitude towards intellectual property rights has been as frankly utilitarian as American approaches over the past two centuries. Like many European countries, China historically had tended to offer favoured parties exclusive privileges that outlawed the copying of particular works. For instance, the Emperor of the North Song Dynasty issued an 11th-century decree, to prohibit unauthorized copying of the Nine Books belonging to Guo Zi Jian. The Qing Dynasty enacted a Copyright Code in 1910 that remained unenforced. After the 1980s, China started to change its approach to copyright, and became a party to bilateral and international treaties like the Berne Convention (1992). Even so, without serious enforcement, copyright statutes did not impede imitation and plagiarism on a national scale.

Then, like the Magical Mr. Mistoffelees, other cats entered stage Right. Deng Xiaoping proclaimed, “I don’t care if the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice,” and the cat of capitalism was released, albeit on a short leash. Market economy reforms partially removed impediments to enterprise, and the rapid expansion of cultural industries motivated protectionist domestic copyright laws. The government prioritized the growth of culture and pursued the Draco-nian goal of “accelerating construction of a Country with Powerful Intellectual Property.” The Beijing Treaty on Audiovisual Performances dated from 2012, but enforcement started just in 2020. Copyright protection quickly expanded to encompass industries from video games and performances to karaoke.

The Enforcers (of Copyright)

As my companion post on the (new) Cultural Revolution discusses, China is now a global leader in online media, film and television. The film industry in China illustrates how their intellectual property policies have endogenously responded to fit these changing economic realities. During the period when the market for domestic films was not well-developed in China, there was little incentive to offer protection for movies. In recent years, however, Asian films and television dominate the global market, in terms of quantity and quality. The top five foreign-language movies, with revenues approaching $4 billion, are all from China (Wolf Warrior 2; Hi, Mom; Ne Zha; Detective Chinatown; the Wandering Earth). The Wandering Earth (2019) box office earnings of $700 million USD can be compared with the $200 million taken in by Crouching Tiger (2000).

As Chinese-made films have become more profitable, concern about intellectual property has become widespread among stakeholders. Huayi Brothers Media Group, which often partners with American studios like Columbia, noted that “the main direction agreed upon is to develop global super IP series, in which case we would expect to profit more from the global market, enhance the influence of our brands and enrich our IP assets.”

The 2017 Film Industry Promotion Law in China imposes stiff punishment for infringement. Copyright enforcement has been framed as a matter of public security, deserving punitive damages and criminal penalties. For instance, in a 2019 case about film and television copyright infringement, the matter was prosecuted by the Ministry of Public Security, along with National Copyright Administration. The defendants, who had made and sold bootleg copies of films and television series, were fined enormous sums, and each sentenced to serve four to six years in prison. High-profile cases against artwork counterfeiters resulted in the prosecutors receiving a Golden Award for copyright protection, from the Chinese authorities and WIPO.

The Red Star Chamber

Copyright has always raised concerns about the potential for curbing individual liberties. The English “Star Chamber Decrees” set out measures to censor and regulate book publishing, until abolished in 1641. During the debates about the U.S. Constitution, concerns were voiced about whether copyright grants were compatible with a free society. Delegates like Robert Whitehill of PA were concerned that “Tho it is not declared that Congress have a power to destroy the liberty of the press; yet, in effect they will have it.”

China directly illustrates the dangers of copyright regulation in an authoritarian society (the link of the phrase to “author” is suggestive). My book, Inventing Ideas, empirically shows how top-down administered innovation systems can lead to arbitrary decisions that enable corruption and arbitrary power plays. Copyright administration in China partly falls under the aegis of the Propaganda Ministry. Large financial subsidies are directed to films and cultural output that favour state ideology. Control is exerted not just over who is accorded the right to write, but also over the content of what is produced, including over media that “endanger social morality or national cultural traditions.” Prohibited topics for movie makers in China range from time travel, zombies, nudity, and talking pigs, to Winnie the Pooh (whom some have uncharitably likened to the Chinese President). In 2018, video game releases were halted for a year for unknown reasons.

The CPC has noted that intellectual property is “powerful.” The most invidious form of power is not overt punishment and control, but self-censorship or voluntary reactions that anticipate future measures. In China, prominent actors have hastened to terminate endorsement agreements with companies that have criticized China’s policies like the Uyghur genocide. Authors excise objective information and critiques from their writing, before the copyright filter can be triggered. A selection effect often operates, where dissident voices must take refuge in foreign countries, while those who declare support for the authorities flourish domestically.

Far from copying the West, cultural goods in present-day China integrate the rich experiences of past millennia, while pushing the boundaries of technological frontiers. This openness of the new Cultural Revolution to the influence of history even extends to the old Cultural Revolution. The popular television series, Awakening Age, dramatizes the struggles of the Chinese Communist Party in the 1920s. It was “hailed by viewers for successfully showing the depth of the CPC’s history and spirit,” and has induced among young viewers a sense of national pride for the heroism and sacrifices of China’s “revolutionary martyrs.”

The Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation finds that over 95 percent of Chinese residents are satisfied with the current political-economic system. What is the appropriate response when an entire society voluntarily elects to give up their freedoms? “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown”?

Related Research

B. Zorina Khan, The Democratization of Invention: Patents and Copyrights in American Economic Development, 1790-1920. Alice Hanson Jones Biennial Prize for best book in American economic history.

B. Zorina Khan, “Accounting for Creativity: Lessons from the Economic History of Intellectual Property and Innovation,” Review of Economic Research on Copyright Issues, vol 17 (1) 2020: 1-37.

B. Zorina Khan, Does Copyright Piracy Pay?

B. Zorina Khan, “Economic History of Copyrights in Europe and the United States,” in EH.Net Encyclopedia, (ed) Robert Whaples, 2006.

B. Zorina Khan, “Le Piratage du Copyright par les Américains au XIXe siècle,” Economie Politique , vol. 22 (April) 2004: 53-73.

B. Zorina Khan and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, “The Early Development of Intellectual Property Institutions in the United States,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 15 (3) 2001: 233-246. Reprinted in Robert P. Merges (ed), Critical Concepts in Intellectual Property Law Series.