Prof. Samuel P. Newman (appointment in Political Economy, 1824-1839).

Samuel Phillips Newman and Bowdoin Economics

In 1824, Bowdoin was the first American College to officially introduce a faculty position dedicated to instruction in Economics (or Political Economy, as it was then known). The University of Virginia in 1826, and Brown University in 1828, followed Bowdoin, when they added faculty slots in this field.

Samuel Phillips Newman (1797-1842), a Harvard graduate, had been initially hired to teach language and rhetoric (his popular textbook in this area went through sixty editions), but he lobbied the College to show a commitment to Economics in the curriculum. As I pointed out in my book, “Inventing Ideas,” early Americans were heavily influenced by the work of Adam Smith, and Newman’s circle was particularly taken with Smithian analysis. Like much of New England, Brunswick was the locus of a take-off in manufacturing and technological innovation in the 1820s. Bowdoin affiliates were at the forefront of these entrepreneurial developments, and Bowdoin College itself can be viewed as an early “institutional investor” in corporate ventures.

Passionate debates developed about economic ideas, and about whether imported theories from European thinkers like Jean-Baptiste Say and Smith applied to the New World. Scholars and intellectuals throughout the Northeast and South offered ad hoc lectures to meet this demand. Between 1820 and 1840, manufacturing productivity and innovation surged, triggering the unprecedented American era of industrialization that would ultimately transform the United States into the global industrial leader by 1870. Prescient observers realized that the ossified standard College curriculum, which largely produced lawyers and clergymen, was failing to meet the demands of a rapidly-growing economy.

Newman helped to generate excitement about the ideas of free markets, patents, technology and economic growth, even before his 1824 official appointment to the newly-created position of Lecturer in Political Economy. His interest in the subject was demonstrably longstanding, as opposed to many of the dabblers who professed expertise in Economics. In 1820, he helped to found the Nucleus Club, with an initial roster of around 90 influential members of Maine society. Newman was on the club’s Political Economy Committee, along with Robert Dunlap (Bowdoin Class of 1815, and later Governor of Maine), and other entrepreneurs and “venture capitalists.”

Newman taught Political Economy before 1824, so the lectureship was most likely formally recognized because of the popularity of the topic. At the time, the curriculum was quite rigid, and all classes listed in the catalogue were required, but professors sometimes offered elective lecture series “on the side.” The named lectureship in 1824, and the addition of Political Economy as a required class for all Seniors, was deemed “experimental,” and was certainly a risky and entrepreneurial move for the College. (Today Economics is no longer required at Bowdoin, although my own view is that Principles should be a prerequisite for voting in national elections.)

Freshman Courses in the 1820s: First Term. Graeca Majora (extracts from Xenophon’s Anabasis and Herodotus) ; Livy (2 books) ; Lacroix’s Arithmetic and Algebra ; Adam’s Roman Antiquities. Second Term. Graeca Majora (extracts from Thucydides and Homer) ; Livy finished (5 books) ; Lacroix’s Algebra ; Adam’s Roman Antiquities finished. Third Term. Graeca Majora (Homer, Isocrates and Xenophon’s Memorabilia) ; Excerpta Latina (Paterculus and Pliny) ; Lacroix’s Algebra finished.

Required Courses for Seniors in 1827: First Term. Astronomy and Mathematics; Paley’s Natural Theology & Evidences ; Nat. Law. Second Term. Political Economy ; Butler’s Analogy; Chemistry. Third Term. Natural History ; Cleaveland’s Mineralogy ; Butler’s Analogy.

Newman published his Bowdoin lectures in 1835 as Elements of Political Economy (second edition in 1844.) This book adapted Smithian insights to suit American institutions and circumstances. (“The author has not deemed it expedient to embrace the opinions of any school of Political Economists. It will be found, however, that he is more indebted to A. Smith’s Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, than to any other work on this science.”) Newman stressed equality of opportunity, which allows active entrepreneurs to acquire wealth, while creating positive spillovers for everyone in society: “A capitalist cannot employ his wealth productively, without benefitting the community in which he lives… he also gives profitable employment to its laborers, and he assists in bringing into successful action those productive powers, and sustaining those economical arrangements, with which the public prosperity is closely connected.”

“So many are the circumstances to be taken into the account, in determining the question of investment, that neither an individual ruler, nor a public body of legislators, can advantageously judge. It is therefore wiser and safer, to leave the whole subject to those who are more immediately interested. The motive to seek after the most profitable mode of investment, is sufficiently strong in every breast; and where the minds of men are in some good degree enlightened, and knowledge is generally diffused, there will be no want of enterprise, or sagacity.”

The treatise promotes a modern approach to economic growth and innovation, underlining the role of individual incentives rather than government intervention. The influence of Adam Smith can be detected in the proposal that technological innovations are induced by profit opportunities. “The immediate object of patent rights is remuneration for useful discoveries and inventions.” Newman argues that patenting will respond to expansions in market demand, and in the long run this is beneficial to both workers and owners of capital. Moreover, the Patent Office enabled new discoveries for better machines and tools that boosted agricultural productivity. The empirical evidence from my own research confirms his perspectives on patenting, and his conclusion that “More probably has been done in this way for the improvement of agriculture, in the United States, than in all other countries.”

Breaking News: Bowdoin Economist Denounced by Karl Marx

Other economists like Amasa Walker of Harvard considered Samuel Newman’s homage to free markets and individual enterprise to be among the best writings on the subject. The book was sufficiently successful as to draw the attention and wrath of Karl Marx! In his classic indictment of capitalism, Das Kapital, Marx scathingly derided the “childish” arguments of “modern economists,” citing Newman’s Elements of Political Economy to prove his point.

Like most free market economists, Newman had a “rational heart,” that was “full of sympathy for every form of suffering,” and committed to increasing social welfare through the most effective means. Students appreciated his dedication: “His genial, unaffected manners, his genuine sincerity and faithful discharge of duty secure the respect and confidence and affection of the students.” Longfellow and Hawthorne were deeply influenced by his teachings, and the latter even boarded in Newman’s house as a freshman student.

Economics and the Common Good

Newman and his peers were not overly concerned about inequality of outcomes, but highlighted the need to find ways to increase opportunities for relatively disadvantaged students, if economic growth was to coincide with advances in social progress. This was evident in his participation in the “Benevolent Society of Bowdoin College,” which provided supplies and interest-free loans to poor students, since 1814. In 1876, the Bowdoin Orient reminded its readers that “Meritorious students with slender pecuniary means may receive considerable assistance from the College.” As such, policies to promote open access to education regardless of income have been a defining feature of Bowdoin College for over two centuries.

Today, Economics remains one of the most popular subjects at Bowdoin. As Samuel P. Newman pointed out, after students take Economics, “Many unfounded prejudices are … removed, the public mind is enlightened, and led to adopt those measures, which are for the public good.”

Bowdoin campus in the 1820s.

APPENDIX: NOTES ON ECONOMICS IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC

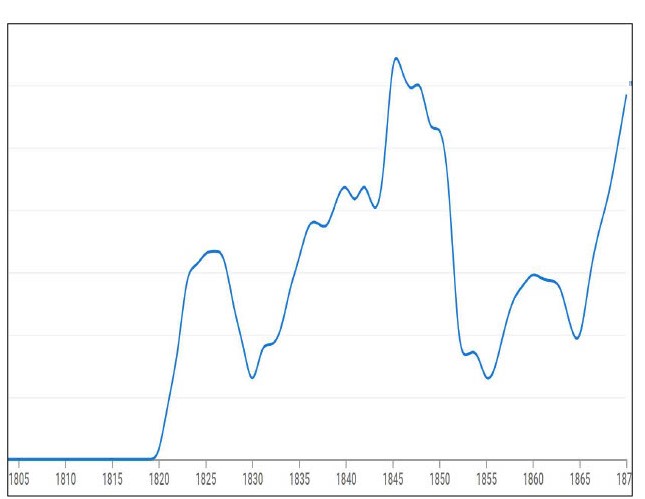

Figure: Frequency of References to “Political Economy” in Books, 1805-1870 (Google Ngram). Shows that in 1824 Bowdoin was in the forefront of academic contributions to the field of Economics.

Lectures and Lectureships: William & Mary (WM) claims it was the first college to offer lectures in Political Economy, based on speculation that their Professors of Moral Philosophy “might” have taught Economics. Ad hoc lectures were undoubtedly presented on related topics in a number of institutions for education during this period. However, the earliest documented source for WM, their Catalogue for 1829, does not include a faculty position in Economics. Moreover, it just lists an eclectic class that seems to emphasize politics more than economics: “Senior Political Course – embracing the Law of Nature and Nations, Government and Political Economy.”

Harvard’s website states that “In 1853, Francis Bowen, a historian and philosopher, was charged with teaching the first courses in political economy for final year students at Harvard.” This actually is not entirely accurate, since Harvard occasionally offered economics lecture courses since the 1820s. Thomas Cooper of South Carolina College in 1824 “recommended” they should introduce courses in Political Economy. Rutgers and Yale similarly included classes in the subject in 1825, but there was no specific professorship/lectureship in the field.

The University of Virginia in 1826, and Brown University in 1828 added faculty positions in Political Economy. NYU in 1831 identified Political Economy as one of the branches to which “professors may be appointed.” There is documented evidence that Columbia College created a position for an instructor of Political Economy in 1836.

Treatises: Early treatises often included speculations by interested amateurs. Daniel Raymond, a lawyer, published Thoughts on Political Economy, in 1820. However, I give him a grade of D for his less-than-persuasive insights: “Although [Malthusian] theory is founded upon the principles of nature, and although it is impossible to discover any flaw in his reasoning, yet the mind instinctively revolts at the conclusions to which he conducts it, and we are disposed to reject the theory, even though we could give no good reason.” The most influential American economists at the time were arguably Henry Carey, (Principles of Political Economy, 1837-40), and Francis Wayland (Elements of Political Economy, 1837).

In sum, there is a great deal of uncertainty about priority in the teaching of Economics courses in higher education in early America, but William & Mary was certainly one of the first. The available evidence reveals no other dedicated faculty appointment at any highly-ranked College or University prior to 1824, when Bowdoin created the Lectureship in Political Economy that Samuel Phillips Newman held from 1824 to 1839.

In sum, there is a great deal of uncertainty about priority in the teaching of Economics courses in higher education in early America, but William & Mary was certainly one of the first. The available evidence reveals no other dedicated faculty appointment at any highly-ranked College or University prior to 1824, when Bowdoin created the Lectureship in Political Economy that Samuel Phillips Newman held from 1824 to 1839.