Like millions of innovative individuals, MIRIAM E. BENJAMIN (1861-1947) was active in multiple inventive markets, as the patentee of two inventions, and assignee on another. However, an overlooked and unique contribution is that she was the first black woman who practiced as a patent attorney.

Miriam E. Benjamin was born in South Carolina to a well-off family with a wide and influential social circle, and developed into an ambitious, confident and persistent young woman. Benjamin trained to be a teacher in a Massachusetts normal school, and in 1884 passed the civil service exam “very creditably,” allowing her to work as a federal government clerk in Washington D.C.

Four years later, in 1888, she enrolled in the Medical School at Howard University, but dropped out in the first year. Numerous sources claim that she obtained a law degree from Howard University, but the college catalogues show that this was not the case. (Charlotte Ray was the first black woman to obtain a law degree from Howard University in 1872, and a total of 34 more women lawyers graduated there by 1940.) However, it was common for patent practitioners at the time to acquire patent expertise through informal means, including apprenticeships, correspondence courses, and learning by doing as patentees. These multiple routes to a patent career promoted diversity, because they were especially valuable for women and other disadvantaged groups.

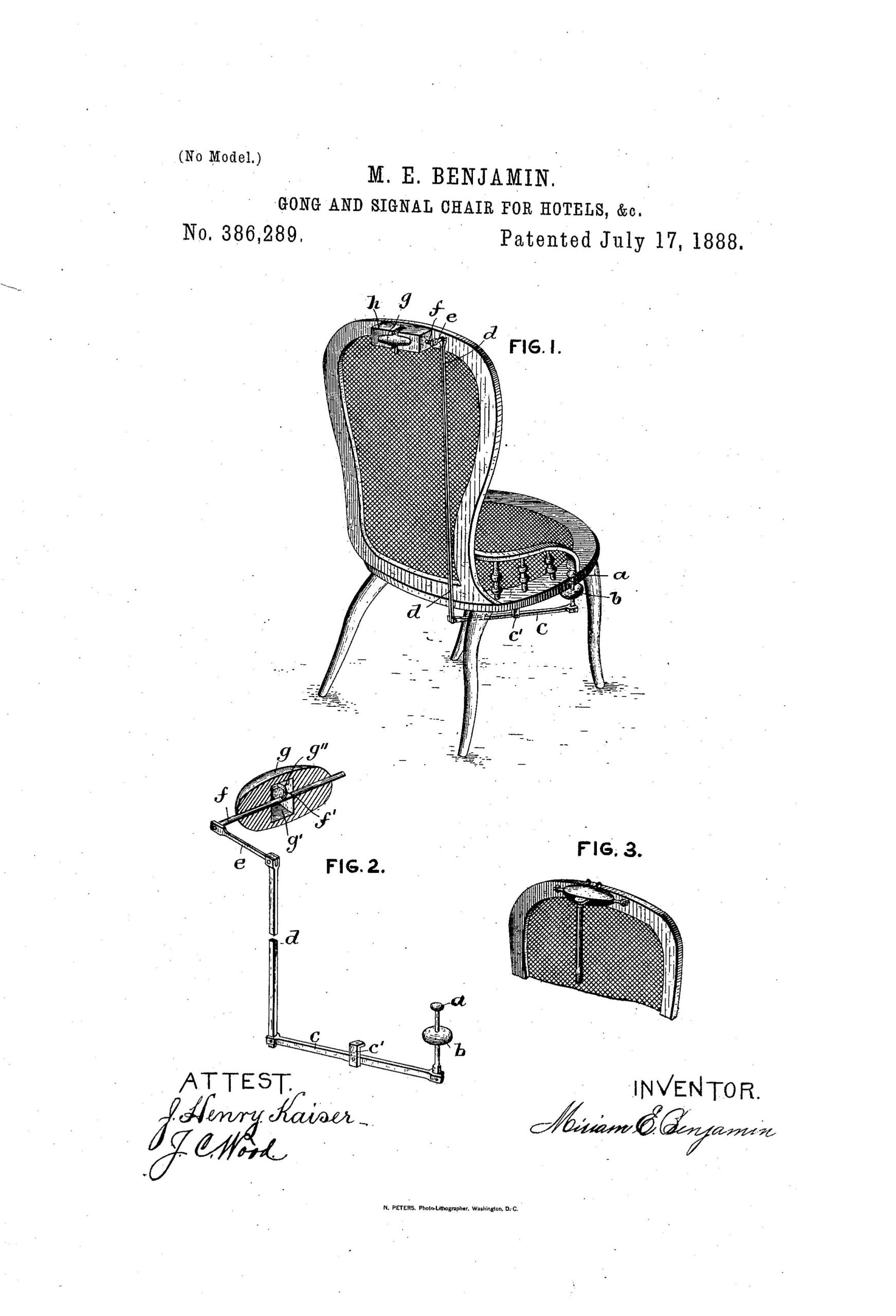

Miriam Benjamin was actively involved in the patenting process, as an inventor and assignee. Her first patent, dated July 17, 1888, was for “gong and signal chairs to be used in dining-rooms, in hotels, restaurants, steamboats, railroad-trains, theaters, the hall of the Congress of the United States, the halls of the legislatures of the various States, for the use of all deliberative bodies, and for the use of invalids in hospitals.” She effectively used the media, and her improvement was widely publicized by newspaper articles and features in women’s magazines. The invention was highlighted at the Atlanta Exposition of 1895. Her second invention was a “sole for footwear” that was patented in 1917 in the United States and in Canada.

“She Persisted” at Law and Legislative Matters

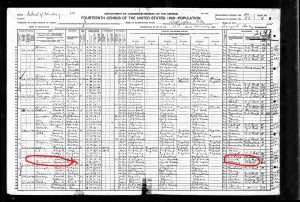

The patent application process was quite transparent, and many patentees completed it on their own account, later setting up businesses as intermediaries for others who preferred to delegate these bureaucratic tasks. Miriam’s brother Lyde Wilson Benjamin (1865–1916) received U.S. patent no. 497,747 in 1893 for an improvement on “Broom Moisteners and Bridles.” The rights to the invention were assigned at issue to Miriam, and she signed the document as the patent attorney (you can view her signature at the bottom of the linked patent drawing). She was similarly the attorney of record, when her younger brother, Edgar P. Benjamin (1869–1972), received U.S. patent no. 475,749 for a bicycle clip in 1892, two years before he graduated from Boston University School of Law. Miriam Benjamin later worked in Edgar’s prosperous general law practice, and the 1920 census lists her occupation as a patent attorney.

1920 census listing Benjamin as a patent attorney

Benjamin’s influence and persistence in legislative matters can be detected in her extended dealings with Congress.*** In 1906, the Boston Daily Globe reported that “Through the untiring efforts of Miss Miriam E. Benjamin of Boston, a clerk in one of the Departments at Washington, $10,482 has been awarded Samuel Lee, a negro, who was elected to congress 25 years ago, but never sworn in.” Benjamin lobbied to bring the bill to aid Samuel Lee before Congress nine times, until it finally passed in 1906. She would similarly provoke efforts on her own behalf for over a decade in the House and Senate, claiming $20,000 (about $300,000 in current dollars) in worker’s compensation for injuries (including a “strained heart” and distress caused by “noisy surroundings and overwork”) she allegedly sustained while working as a clerk at the Government Printing Office in 1910.

Claims and Disclaimers

The origins of current inequality can be detected in historical patterns and outcomes, but both present and past sources include many inaccuracies and false claims. Patent records therefore provide invaluable objective information that shed light on the actual – rather than invented — experiences of underrepresented groups. Henry E. Baker, a black patent examiner who was appointed in 1876, underlined that the patent system was “colorblind;” and neither the laws nor the administration excluded or differentiated on the basis of personal characteristics. Claims that black inventors filed patents under the names of white attorneys seem absurd: under U.S. patent laws, any such patents would be invalid, as even the most incompetent lawyer would know; and there was no reason at all to do so, since all applications were submitted in writing and it was impossible for anyone at the patent office to identify the inventor’s race.

Patent grants allow us to objectively prove novelty and priority. Benjamin was granted patents for her ideas, and this is sufficient to demonstrate that her discoveries were original and distinct from previous inventions. From a broader historical perspective, she was not the first black inventor (Thomas Jennings obtained a patent in 1821), nor the first black woman patentee (Judy W. Reed, in 1884, was prior). Patent records also refute the common tendency to attribute an entire industrial category to a single inventor – in fact, over 800 similar signalling devices were filed before 1910, and dozens prior to Benjamin’s own invention.

Patent Office documents instead suggest Benjamin has a stronger claim to priority as a black patent attorney. She may have obtained informal legal training, but that is pure speculation, without any reliable supporting evidence. Her listing in the 1920 census as a patent attorney is certainly notable, but the census takers simply recorded what householders told them. However, the two patent applications for her brothers’ inventions offer direct proof of her standing as a patent practitioner, including her actual signature. When combined with the census entry, these documented sources confirm the validity of the statement that “Miriam E. Benjamin was the first black woman to practice as a patent attorney.”

***I am indebted to Barbara Levergood of the Bowdoin College library and Renée Bosman at UNC-Chapel Hill, for their generous assistance in locating these bills.