The Biden Executive Order on Promoting Competition once again targets patents, this time as anticompetitive. A lot of the hostility to patent grants is due to the casual observation that “patents are monopolies.” Every school child learns that monopolies are bad because they drive up prices and contrive scarcity. Populists today are chanting the same refrain that patents result in vaccines being overpriced and underprovided, and this is in part behind the movement to overturn patent rights. Let’s consider three central questions.

1. What is the relevant counterfactual? When people say higher prices and lower output, we should always ask “relative to what?” The simplistic monopoly model is analyzed relative to an even more simplistic model of perfect competition in a market where the invention already exists. In this hypothetical Nirvana, there are a large number of perfect substitutes, lots of small firms with no market power, and zero product differentiation. According to this way of thinking, the nefarious monopolistic robber baron stumbles upon an invention that would otherwise be available to the public at a low price, and then proceeds to oust competitors, in order to cut back on output and increase the price. The monopolist is taking something that could belong to the public and making it his own.

This sort of simplification has serious consequences, leading to the notion that patents for vaccines somehow rightfully belong to the public. Patentees have benefited society far more than (say) coffee plantations, but nobody would propose overturning property rights in bags of coffee, regardless of the price of Blue Mountain beans. In the final analysis, Nirvana might not be so perfect in reality, because in the absence of patents it is unlikely that any firm would invest in risky upfront R&D to find a vaccine. In the absence of patents, society would not possess the information to make substitutes. In the absence of patents, the market for ideas would lead to outcomes that are far more imperfect.

But whatabout the higher prices? If prices for a new discovery were higher than for the older substitute, consumers are still free to purchase the cheaper alternative if they wished. Don’t want to pay for a vaccine? Well, there are substitutes (masks/social distancing) and the fact that they are imperfect would suggest we should be willing to pay a lot more than $20 or $30 for a lifesaving vaccine.

“As to the pretext, that grants of exclusive property . . . tend to enhance the price of the newly invented manufactures; it may be answered that, as such grants do not compel any one to purchase these new manufactures, the public are left at liberty, at the lower price, to buy the old: and this they will certainly do, neglecting the new, if their superiority of merit be not adequate to the advance of price.” Kenrick, An Address to the Artists and Manufacturers of Great Britain (1774)

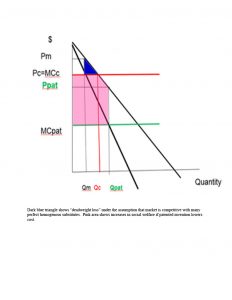

Many new patented inventions have dramatically lowered production costs and prices, and increased output (see the figure below). The millions of patented discoveries we now enjoy have conjured a cornucopia of entirely new products and markets that previous generations could not even have imagined.

2. What does IP history say about “patent monopolies”?

British patents were regarded as an exception from the general prohibition against monopolies in the famous 1624 Statute of Monopolies. The Crown had long given out privileged rights to favourites who engrossed the market for extensive arrays of goods and services, ranging from salt to the running of transportation. These were true monopolies, which imposed barriers to entry and drove up prices, injuring the public.

Similarly, although patents were supposed to be for new inventions, there was no examination to verify novelty or ownership of the idea. Owners of firms could acquire the patent right to an invention created by their employees. As long as you could pay the exorbitant fees (10 times per capita income), you had the right to get a patent. These fees and other costs offered valuable revenues to the government, but functioned as a barrier to entry for ordinary people without connections or capital, even if they had a better idea. The patent was viewed as property of the Crown, that was graciously bestowed upon the supplicant, and the King or Queen had the right to take back the patent without compensation (in the manner of a Biden-like dispensation via a temporary or permanent waiver.)

The American patent system introduced many innovations. It was the first time that a patent clause was included in a national constitution. To “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts [rather than to grant monopolies to a favored few, or raise public revenues], by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” — U.S. Const. Art. 1

Patents were granted as a “right” (the only time that this word appears in the Constitution), as an incentive for economic growth and innovation.

Many of the Founders were concerned about monopolies: “Resolved, as the opinion of this committee, that nothing in the said Constitution contained shall be construed to authorize Congress to grant monopolies…” – NY State Debates on Federal Constitution, 1788.

Why then, was the IP clause the only one to pass unanimously and without debate? The answer is that patents in the new American system were not monopoly grants that set up barriers to entry. Instead, they were crafted to be strong property rights, which are a necessary prerequisite for market exchange and innovation. The enforcement of property rights are not the same as a monopolistic barrier to entry.

It was clear to nineteenth-century American jurists and legislators that property rights in patents were not monopolies. “No exclusive right can be granted for anything which the patentee has not invented or discovered. The right of the patentee entirely rests on his invention or discovery of that which is useful, and which was not known before… [A monopolist] takes from the public that which belongs to it, and gives to the grantee and his assigns an exclusive use…. Under the patent law this can never be done… If he claim anything which was before known, his patent is void, so that the law repudiates a monopoly… This, then, in no sense partakes of the character of monopoly.” –Allen v. Hunter, 6 McLean 303 1855

“The inventor has, during this period, a property in his inventions — a property which is often of very great value and of which the law intended to give him the absolute enjoyment and possession… involving some of the dearest and most valuable rights which society acknowledges and the Constitution itself means to favor…” –Ex Parte Wood and Brundage, 22 U.S. 603 (1824)

“But for the patent laws there would, probably, be but one printing-press company, but one typewriter company… but one adding-machine company, but one of many now listed in the thousands.”

–[Hearing, 62nd Cong. 10 (1912)]

The fact that Pfizer has a set of patents on specific pharmaceuticals does not prohibit other firms from finding other drugs for the same ailment. At the moment, there are dozens of viable covid vaccines, and more are in development. In other words, patents typically increase the number of substitutes and competition in the market; and obviously, patented ideas do not necessarily confer monopoly in the product market. As early American law and policy makers emphasized, we should regard patentees as benefactors rather than monopolists.

3. Is the next best alternative better? As for the “deadweight loss” that elementary economics assigns to patent monopolies, even if that were true, alternatives to patents result in even more substantial deadweight losses.

I’m not sure what a chemistry researcher knows about economics, even if he has a Nobel Prize, but one of them is lobbying to get rid of the monopolistic patent system and publicly fund innovation. This sort of data-free armwaving ignores the fact that alternatives to patents such as innovation prizes and government grants enable monopsonies. These administered systems are associated with serious efficiency concerns, including cronyism and corruption, a lack of diversity, and the potential for unjust discrimination and rent-seeking.

“Not that the system as developed in this country or anywhere else is perfect; no one claims that; but it is infinitely better than any substitute for it that has ever been proposed.” “Our Patent System and What We Owe to It”James Richardson, Century Magazine (1878)

Figure: Example of a patented invention that increases social welfare relative to competition.