(Yet another) First Women’s Bank:-

The First Women’s Bank, opened in 2021, claims to be the “nation’s first women-founded, women-owned, and women-led bank dedicated to closing the gender equity gap in access to capital.” But it is easy to demonstrate that the First Women’s Bank is far from first on each and all of these counts, and in fact is not even the first in Chicago. Suffragists like Susan B. Anthony felt that financial votes for women were as potent as political votes, so it would be rather odd if no such institution had existed over the course of American history.

As my comprehensive database of over 40,000 antebellum investors shows, American women shareholders provided funding for the industrial revolution in all areas of the economy, especially in banks and other financial institutions. Martha F Trask of Portland, Maine was the largest investor in Manufacturers’ and Traders’ Bank (incorporated in 1831); and women were also the majority shareholders in the Medomak Bank of Waldboro, and the Exchange Bank of Bangor. The number of female executives and bank owners increased markedly towards the end of the nineteenth century.

The Frequency of Unique Women’s Banks

Many female-oriented businesses, each claiming to be the first of its kind in the country, attempted to motivate women to exercise their economic power and governance. More than a hundred years ago, a Chicago bank “controlled by women and for women exclusively” was chartered in 1910 with a capitalization of around $25,000. The founder was Miss Kate F. O’ Connor, a wealthy self-made entrepreneur in Rockford, Illinois, along with Mrs. Antoinette Funk, an attorney.

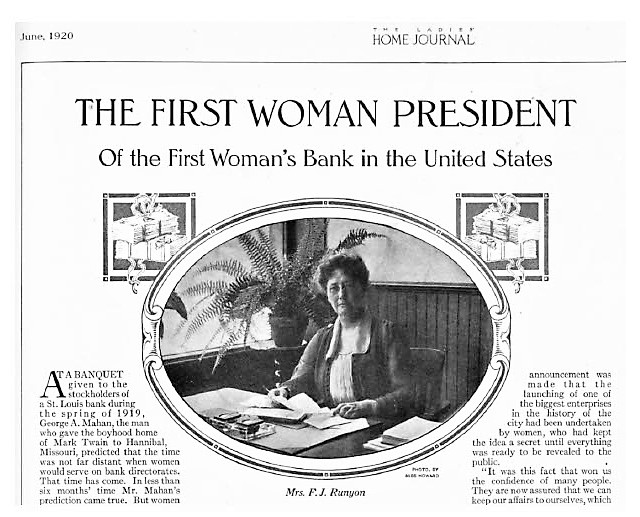

The New York Times notified their readers of the founding of “A Bank for Women All to Themselves,” in September 1906. In 1919, “a” (rather than “the”) First Woman’s Bank was established in Clarksville, Tennessee, with Mrs. Brenda V. Runyon as president, and the stock offering sold above par. The Bank was located in the Montgomery Hotel Building, which was also owned by a woman, and billed as “the first of its kind in the whole world to be organized and controlled entirely by women, all of its officers and directors being women.”

In 1922, Flora Andrews was elected President of the Women’s Savings Bank & Loan Co. of Cleveland, optimistically claiming capitalization of $1 million, “catering especially to women, with women alone to guide its policies and its employees from teller to janitress and all officers women.” The Indianapolis Times reported yet another “Woman’s Bank Unique in U.S.,” in October 1920. In 1925, Woman Today featured the entry into the market of “AN ALL-WOMAN BANK: Cleveland has a new mortgage company, organized and managed by women – Ohio Mutual Mortgage Company. Satisfied with the success of the Women’s Savings and Loan Company, the first women’s saving company in the country, Miss Lillian Westropp, president, and Miss Clara Westropp, secretary, decided to open a mortgage company,” whose employees and customers were women.

Many such institutions were chartered in other countries. A modest women’s bank was founded in China in 1910, but a decade later the Chinese Women’s Commercial and Savings Bank was capitalized at $500,000. The Berlin Mutual Bank for Independent Women (1910), operated as a female cooperative, with 5,000 GBP in capital and offering small loans limited to 25 GBP only to women. The bank was “presided over exclusively by women,” so the “feminine touch” was evident in the presence of cut flowers, lace curtains, and “a counter redolent of marguerites and lilac.” The Woman’s Savings Bank of Toronto notably varied from this model, by instead offering “the subtle odor of violets and attar of roses.”

The famous/notorious Tennessee Claflin, with her sister Victoria Woodhull, had launched the first women-owned brokerage on Wall Street in 1870. After her marriage and ascension to the peerage as Lady Cook, she was the head of a private stock brokerage, Lady Cook & Co, in the 1890s in London. She declared the intention to fund a women’s bank in 1910, but it is not known whether the project succeeded. However, in the same year, London newspapers proclaimed “a novel departure in British Banking,” in the form of “a woman’s bank, officered and conducted exclusively by women and catering only to women customers.” They noted that “people who wear whiskers will be shooed away,” by the sole male employee, hired for that purpose.

Women-only businesses existed in many other sectors, including manufacturing, legal services and publishing. For instance, in 1892, the Women’s Publishing Company of Minneapolis was organized with an all-women cast of executives and employees, and the shares were tendered to women alone. Similar enterprises included The Business Women’s Publishing Company, Denver in 1903, with a capitalization of $50,000; and the New York Women’s Publishing Company, incorporated in May, 1918.

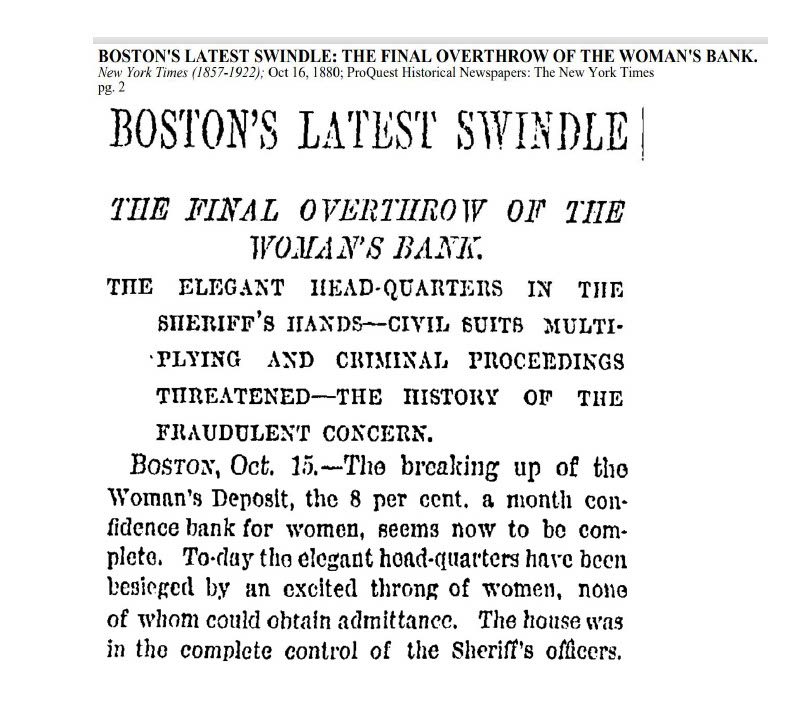

Equal Opportunity Fraud

The very first all-women’s bank should perhaps not be celebrated — it was founded in 1878 through the criminal initiative of Sarah Emily Howe (1826-1892). Her enterprise specifically targeted women, and got off the ground without an official charter in Boston. As President of the women’s bank, Howe promised her clients they would receive the staggering return of 8 percent interest per MONTH on their deposits. The motivation of the bank was not mere profit, she assured prospective depositors who voiced qualms, but rather Quaker philanthropy and a keen appreciation of the difficulties that suppressed women in a male-oriented world. Attracted by these tempting returns, around 1200 women rushed to hand over a total of $350,000 to the bank.

Howe was an inveterate perpetrator of the classic financial fraud, where the assets of newcomers were used to make payouts to earlier claimants. An enterprising male journalist uncovered the scheme by disguising himself as a woman to gain entry to the bank. His articles exposed the con and undermined the credibility of the venture, which led to a run on the bank. Howe was jailed, but on her release from prison immediately returned to the financial scene of the crime, founding another Women’s Bank that offered unsustainably high rates and attracting yet more gullible clients who would go on to lose all their savings.

Qui Bono, Argentaria Mulierum?

(Which can be translated as, What’s the good of five years of Latin, if you can’t randomly insert a cryptic phrase in your writing?)

The world of finance is competitive, and market efficiency implies that transactions should be independent of the identities of the parties on either side of the exchange. Why then would there be a need for a “women’s bank” in the modern economy of the 21st century, beyond a marketing gimmick? If capital market imperfections lead to systematic mispricing by gender, perhaps owing to irrational bias or to asymmetric information that is revealed only to other women, it is possible that a women’s bank might generate greater profit than an “open bank.” If not, such institutions will only be able to persist through subsidies from the state or private philanthropy, and perhaps would do better to register as a nonprofit enterprise.

The historical evidence shows that women’s institutions were typically undercapitalized, and most did not outlast their founders. For instance, the First Woman’s Bank of Tennessee had a capital stock of $15,000, and was liquidated after its president resigned in 1926. In 1900, Mary Elizabeth Miller (1842-1921) founded the Lafayette Bank and served as its elected President, with the intention of helping other women and workers. During the not infrequent strikes, she would introduce a moratorium on workers’ outstanding mortgage payments. Among her “most important and unsung accomplishments was helping women achieve financial independence.” She favoured women in banking and real estate transactions, often selling them land at below-market prices. Not unexpectedly, the bank failed in 1914.

The Women’s National Bank, which was founded in 1978, became an “open bank” eight years later and changed its name to The Adams (surely The Eves would be more appropriate?) Bank. According to its CEO, the change occurred because the women’s movement was “ready to enter the mainstream.”

All of this suggests that the “First Women’s Banks” of the 21st century will be able to make history by simply surviving.