The advent of 5G cellular technology has induced imaginative speculations about spectacular virtual universes, Humans 3.5 artificial intelligence, and an Internet of Things that will trigger “smart houses” and even smarter cities. What lessons can earlier telecommunications inventions offer? The focus here is on five issues regarding 5G: the social savings from new innovations; business to business (B2B) relative to consumer markets; private sector versus government-led initiatives; net neutrality; and the right to privacy.

Dots, dashes and ring tones

The “T&T” in American Telephone & Telegraph arguably represents the most disruptive telecommunications inventions in history, with the greatest social savings relative to prior alternatives. All the romance of a completely new era was imbedded in these inventions, or as the 1879 novel Wired Love put it, they conveyed “the old, old story, — in a new, new way.” Before telegraph wires connected the globe, communication was slow, risky and unreliable. New York immigrants to California might not obtain a reply to a letter from relatives for an entire year. Samuel Morse, as an art student in London, wrote to his family: “I wish that in an instant I could communicate the information; but three thousand miles are not passed over in an instant, and we must wait four long weeks before we can hear from each other.” He was in Washington DC in 1825 when his young wife died in New Haven, and he did not receive the news until many days later.

5G: does the “G” stand for government?

The telegraph ushered in the modern information economy, instantly spanning time and space. Congress reluctantly funded the first line between Baltimore and Washington in 1844, but in the United States the industry developed through the initiative of the private sector. Telegraphy diffused so rapidly that 75 companies with over 20,000 miles of wire were in operation just a decade later. These small-scale enterprises proved to be inefficient, and a series of consolidations and exits ultimately resulted in Western Union’s control over ninety percent of the telegraphy market by 1865. In the case of both the telegraph and the telephone, the initial use was primarily limited to businesses, and consumer demand remained low for several decades. Despite the hype, this is also likely to be true of 5G.

In European countries, mercantilist approaches prevailed, with governments determined to own and control new telecommunications industries. The telegraph was regarded as essential for national security and the military, and was either owned or operated by the state. The French government constructed the telegraph system in 1845 and monopolized its use, arguing that “the telegraph must be a political, and not a commercial, instrument.” In England, the government decided to nationalize the telegraph business in 1870, and turned its control over to the state-owned Post Office.

In European countries, mercantilist approaches prevailed, with governments determined to own and control new telecommunications industries. The telegraph was regarded as essential for national security and the military, and was either owned or operated by the state. The French government constructed the telegraph system in 1845 and monopolized its use, arguing that “the telegraph must be a political, and not a commercial, instrument.” In England, the government decided to nationalize the telegraph business in 1870, and turned its control over to the state-owned Post Office.

In the United States, similar arguments were put before Congress, and Western Union was the target of almost a hundred legislative initiatives that unsuccessfully attempted to overturn its “monopoly of knowledge.” Few at that time could have predicted that Western Union’s future market power would derive from its novel innovations in online financial intermediation and credit cards, rather than the telegraph itself. And even fewer would have conceived of AT&T’s role in the new market for the “telephonic telegraph.” AT&T was dominant owing to its cutting-edge research, extensive portfolio of essential patents and intellectual property, economies of scale and scope, and the connectivity of its hardware and software.

Unlike other countries, the U.S. telegraph and telephone industry remained under private ownership. The decision not to nationalize the telegraph was due to a realization that the buyout and operation would be an unprofitable drain on the exchequer, and to the unpopularity of such measures among the American electorate. Public aversion to government control over key innovations temporarily ebbed during public crises such as during the Great War, but (apart from the government monopoly on postal service) the United States generally avoided public ownership of enterprises. Companies like AT&T were regarded as natural monopolies, and subject to regulation of varying degrees. As a result, when AT&T was charged with violation of antitrust, one of its novel defenses was that its actions were due to government regulation.

The 150th anniversary of the demise of net neutrality

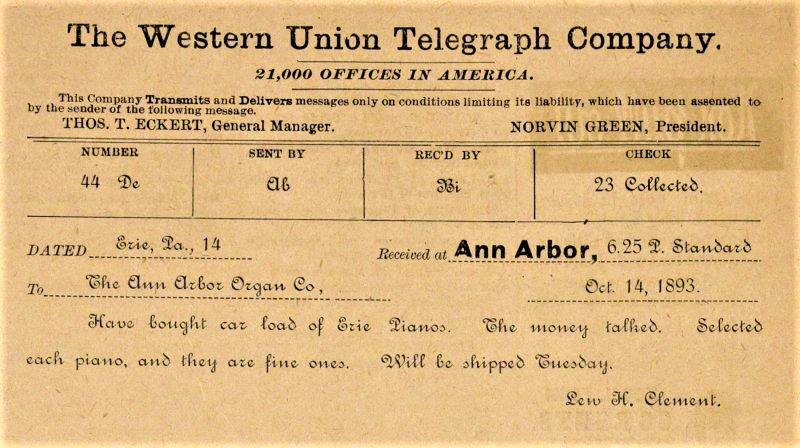

Net neutrality is an “old, old” concept that originated in the common carrier status of railroads (featuring literal platforms!). Built along the railroad tracks, telegraphs were arbitrarily held to have inherited the railroad’s common carrier status. The common carrier designation prohibited price discrimination, and initially implied assumption of liability for the “goods carried.” Under this doctrine, an error in transmitting a buy or sell order could lead to many thousands of dollars of damages assessed against the telegraph company. At the same time, unlike consignments on railroads, the intrinsic value to the telegraph company of the messages it transmitted was much lower than the value to the sender or receiver of the message. The courts rejected the analogy to common carriers, focusing on the personalized and customized nature of messages “carried.” Western Union was justified in charging higher discriminatory rates for important or encrypted messages, because this allowed the firm to reduce the problem of asymmetric information. Camp v. W. Union Tel. Co. (1858) noted that “it does not exempt the company from responsibility, but only fixes the price of that responsibility.” The Supreme Court, in Primrose v. Western Union Telegraph Co. (1894), subscribed to these state doctrines, holding that “Telegraph companies … are not common carriers; their duties are different, and are performed in different ways; and they are not subject to the same liabilities.” Ironically, these early insights about the efficiency of differential tariffs in the information economy have been lost in politicized discussions of “net neutrality” for internet transactions. The resuscitation of net neutrality would constrain the efficacy of customization and “network slicing” in the next generation of telecommunications innovations.

The courts rejected the analogy to common carriers, focusing on the personalized and customized nature of messages “carried.” Western Union was justified in charging higher discriminatory rates for important or encrypted messages, because this allowed the firm to reduce the problem of asymmetric information. Camp v. W. Union Tel. Co. (1858) noted that “it does not exempt the company from responsibility, but only fixes the price of that responsibility.” The Supreme Court, in Primrose v. Western Union Telegraph Co. (1894), subscribed to these state doctrines, holding that “Telegraph companies … are not common carriers; their duties are different, and are performed in different ways; and they are not subject to the same liabilities.” Ironically, these early insights about the efficiency of differential tariffs in the information economy have been lost in politicized discussions of “net neutrality” for internet transactions. The resuscitation of net neutrality would constrain the efficacy of customization and “network slicing” in the next generation of telecommunications innovations.

A Future Economic History of 5G

5G wireless service promises to enhance the speed, connectivity and latency of transactions. As Robert Fogel warned in the case of the railroads, there is a danger of over-optimism when one attributes the total benefit from an industry to a new technology. Instead, any innovation like 5G comprises an incremental improvement over the existing telecommunications infrastructure. As such, the economic analysis of its benefits or “social savings” must take into account the surplus generated in excess of the next best existing alternatives. Estimates of social savings from 5G need to be adjusted for the benefits already accruing from 4G. Moreover, after incorporating the costs associated with an innovation, the net overall benefits might even be negative, as this WSJ article about faster internet speeds concludes.

All “great inventions” consist of a myriad of incremental small inventions. Similarly, 5G is not a single discrete discovery, emerging fully-baked like bread, but a step in a process that will require years, if not decades of improvements to fully realize its potential. In the near term, in keeping with the development of prior telecommunications inventions, business to business transactions will benefit the most, and direct benefits to consumer will not appear until the long run. For instance, robotics and device to device connectivity lowers the cost of production, which offers indirect economies for consumers. However, the applications to engage ordinary consumers have not yet been created and, just as in the case of the telegraph, it is impossible to predict the directions in which end user innovations will evolve.

Antitrust and 5G markets

In the world of new technological innovation, populist government regulators and antitrust authorities are like drivers who navigate using their rearview mirrors alone. Populism today is based on the same tired policies directed toward Standard Oil, with calls for the breakup of tech firms, whose success derives from successfully meeting consumer demand. Firms with essential vaccine patents risk their expropriation by the state, short-sighted proposals that undermine two centuries of U.S. intellectual property policies.

Amazon is a leader in online markets because consumers freely choose its goods and services over all other options. Far from the “fat and lazy” monopoly model, the firm is relentlessly competitive, in keeping with its mantra of “every day is day one.” In their primary markets, Google and Facebook offer free services and thus attain competitive output levels, while profiting from complementary markets for information and advertising in which they face numerous competitors.

The Sherman Act of 1890 resulted from a political exchange between Senators McKinley and Sherman, to ensure protectionism for failing firms in the modern world of global competition. The tools and models of antitrust are all the more irrelevant to the 21st century, as rapid technological innovation in 5G (and future N-Gs) continually erodes and rewrites market definitions and relationships between participants. Antitrust concerns about collusion might inhibit productive collaborations. Moreover, 5G-driven connectivity reveals the weakness of the conventional “market concentration” approach. Firms like Qualcomm and Ericsson at present are positioning themselves for the next generation of innovations by diversifying into adjacent markets: drones, automotive services, and cloud-computing. It becomes difficult, if not impossible, to determine market power when self-driving automobiles connect with repair bots, insurance companies, and ride-share services; and drones are employed in cameras, movies, and deliveries. Meanwhile, to compete in future markets, former antitrust targets like IBM and GE are following AT&T by breaking themselves up.

It’s yesterday once more

Populists frequently characterize innovation as a race with one winner, which requires top-down state intervention to ensure national dominance. The Chinese state is investing heavily in 5G infrastructure, buying equity in new ventures, and offering subsidies to domestic enterprises, although it’s unclear that its actions have significantly added to productivity. If the conversation around this technology is phrased in terms of catching up with China, there is likely to be a strong lobby proposing that the U.S. federal government should be similarly involved. Predictably, some on the National Security Council have already suggested the U.S. federal government should nationalize the 5G network, to allow America “to leap ahead of global competitors and provide the American people with a secure and reliable infrastructure.” Firms with large numbers of “essential” patents are likely to encounter threats of expropriation in the name of national security or consumer welfare.

But, as my book Inventing Ideas indicates, technological innovation in nations and firms is not a zero-sum race, with a single winner and everyone else a loser. All players can win if they cooperate. As messy and error-prone as it might seem, the most effective model is a decentralized approach, based on private enterprise and the strong protection of intellectual property rights. American firms will best succeed if they can productively collaborate with domestic and foreign counterparts, with access to overseas consumer markets. Notions of “net neutrality” and state intervention met their demise in the nineteenth century, and antitrust models and antitrust tools from the Sherman era seem even more irrelevant to modern innovation markets. This suggests that, as always, the foremost role for the state lies in the removal of government-imposed obstacles, such as outdated competition policies, inefficient federal allocation of needed spectrum, harmful tariff and trade barriers, and the attrition of property rights in ideas.

The Internet of things and the right to privacy

In 1890, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis successfully lobbied for legal recognition of The Right to Privacy, to counter the infringement of individual rights from new technologies. The advent of 5G and the Internet of Things holds both the promise of widespread benefits and the threat of a massive erosion of individual privacy. The customization of products and services to reflect personal preferences, connections across firms and devices, facial recognition technology and digital surveillance, all raise the spectre of an antidemocratic loss of individual autonomy. Indeed, at the moment over 80 percent of those surveyed feel that the risks of data-sharing outweigh the benefits. Businesses can always make scalable investments in security to protect their data, but far greater transparency and agency is needed for ensuring the responsible use of consumer data and information. As Justice John Roberts emphasized in Riley v. California (2014), “The fact that technology now allows an individual to carry such information in his hand does not make the information any less worthy of the protection for which the Founders fought.”