According to such usually reputable sources as Forbes and the Guinness World Record, in 1919 Madam C. J. Walker was the “first self-made millionairess” in the United States. As my accompanying post, In Search of Hetty Green, demonstrates, this is far from accurate. In fact, Walker was not even the first black or minority woman who acquired enormous wealth from her own efforts. Many of their stories will never be retrieved because no records survive, but here I will focus on a few illustrative documented accounts.

Gold Rush in New York and San Francisco

Brooklyn Heights in the Nineteenth Century

Brooklyn Heights in the Nineteenth Century

Elizabeth A. Gloucester (1817-1883) was often labelled as “the richest colored person of New York,” and a woman who moved in “aristocratic circles.” While she was alive, her holdings were valued at over $1 million, accumulated through her own enterprise. Gloucester started from the humblest beginnings, and kept as a souvenir the savings book from her first bank account, opened in Philadelphia when she was a young domestic servant. Her fortune was realized through thrift, savings, and “investing up” by selling at a profit and buying increasingly more valuable assets. One of her most successful investments was the Remsen House, a large elegant boarding house that she managed for some twenty five years. This exclusive establishment was popular with medical-school professors, judges, politicians, and other elite professionals. Her wealth appreciated through other shrewd investments in businesses and real estate in Brooklyn Heights and Manhattan. She ensured her children were well-educated, and donated $100,000 to the college they had attended. Gloucester offered financial support for John Brown and the Underground Railroad, and throughout her life was a generous contributor to African-American charities.

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1904) possessed a daring and compelling character, and her biography makes for a picaresque narrative. She was born in Pennsylvania, and migrated to California during the early years of the Gold Rush. This colourful frontier provided the ideal canvas for her creative drive and readiness to undertake bold ventures. She quickly built up a diverse portfolio of assets in San Francisco, conducted an exchange in gold and silver, and was “well-known to the old-time stock speculators on Pine Street.” These investments included an upscale boarding hotel with wealthy residents, restaurants, laundries, shares in banks like Wells Fargo and the Bank of California, and numerous lucrative real estate deals. Some of her profits may have accrued from inside information she obtained while serving politicians and entrepreneurs. In 1895 she filed a lawsuit in the San Francisco superior court to recover debts of over $22,000 from a merchant.

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1904) possessed a daring and compelling character, and her biography makes for a picaresque narrative. She was born in Pennsylvania, and migrated to California during the early years of the Gold Rush. This colourful frontier provided the ideal canvas for her creative drive and readiness to undertake bold ventures. She quickly built up a diverse portfolio of assets in San Francisco, conducted an exchange in gold and silver, and was “well-known to the old-time stock speculators on Pine Street.” These investments included an upscale boarding hotel with wealthy residents, restaurants, laundries, shares in banks like Wells Fargo and the Bank of California, and numerous lucrative real estate deals. Some of her profits may have accrued from inside information she obtained while serving politicians and entrepreneurs. In 1895 she filed a lawsuit in the San Francisco superior court to recover debts of over $22,000 from a merchant.

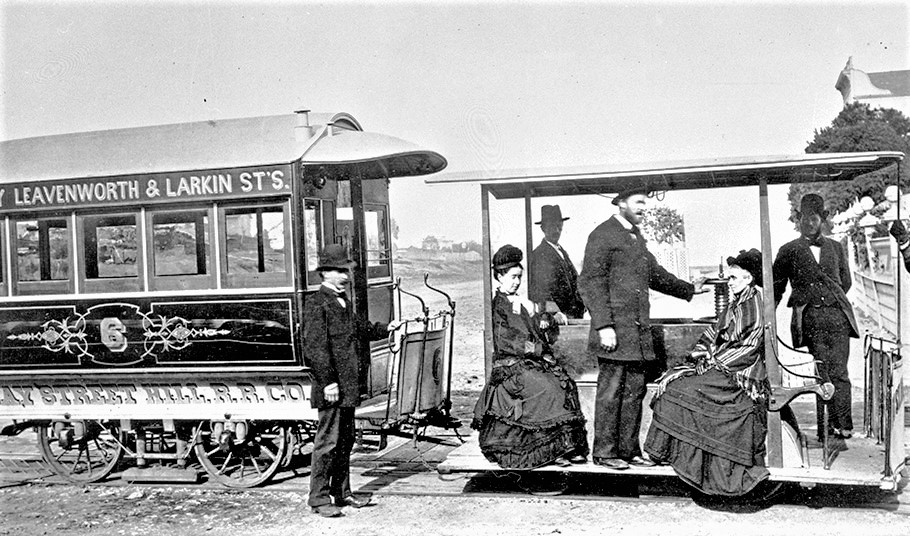

Her most famous litigation, however, was in the landmark civil rights case, Pleasants v. North Beach & Mission Railroad, 34 Cal. 586 (1868). Long before Rosa Parks, Mary Pleasant effectively protested against segregation and discrimination on public transportation. In 1866, she was waiting for a streetcar, but it failed to stop for her: “The facts of this case are that the female plaintiff, (who is a woman of color,) being desirous to take passage on one of the street cars of defendant, hailed the Conductor and requested him to take her on board; that he disregarded her signal and failed to stop, and by reason of his declining to stop she was unable to get upon the car. It was also proved, under objections from the defendant, that the Conductor on being urged by a lady passenger already in the car to stop the car for the plaintiff, replied: “We don’t take colored people in the cars;” … the jury having retired, without any charge from the Court, returned a verdict for the plaintiff for five hundred dollars.” Like Elizabeth Gloucester, Pleasant donated large sums to support John Brown and other philanthropic causes to benefit black citizens.

Oklahoma Oil Baronesses

Oil was discovered in Oklahoma Territory in 1859, and the state went on to produce the most oil in the United States until California entered the market. The U.S. Treaty of 1866 with the Five Civilized Tribes allocated land to “Freedmen,” or freed black slaves and their children. As a result, numerous American Indians and black Freedmen who owned oil-rich land in the region became millionaires during the nineteenth century. In 1911, when the United States Court of Claims awarded title in oil fields to another group of former slaves, this decision created hundreds of instant millionaires. Some benefited from windfall gains without any effort of their own, but others actively managed both their finances and investments beyond their oil holdings.

Oil was discovered in Oklahoma Territory in 1859, and the state went on to produce the most oil in the United States until California entered the market. The U.S. Treaty of 1866 with the Five Civilized Tribes allocated land to “Freedmen,” or freed black slaves and their children. As a result, numerous American Indians and black Freedmen who owned oil-rich land in the region became millionaires during the nineteenth century. In 1911, when the United States Court of Claims awarded title in oil fields to another group of former slaves, this decision created hundreds of instant millionaires. Some benefited from windfall gains without any effort of their own, but others actively managed both their finances and investments beyond their oil holdings.

National newspapers continually reminded its readers that “Oklahoma Has Many Wealthy Afro-Americans.” Sarah Rector (1902 – 1967) was well known during her lifetime as the youngest black millionaire, and the person with the highest annual income in Oklahoma. The Chicago Defender of 1914 featured her story as the “Afro-American Girl Worth $1,000,000.” As a child, she and each of her family members were allotted land in Oklahoma, and her tract consisted of 160 acres of what turned out to be among the richest oil fields in the state. The first of her wells, the Jones Gusher, was the biggest-producing in the region, yielding 2500 barrels of oil each day, while other drills increased the total daily output to 3,800 barrels. She owned a diversified portfolio consisting of stocks, bonds, commercial and residential properties, businesses, and extensive land holdings. Others in similar circumstances included Rachel King, whose wealth at age 14 exceeded $1 million, Isabel Lewis, Josephine Morrison, Gracie and Maud Glenn, and their mother Mrs. R. J. Glenn.

Similarly, American Indian women, such as Maude Lee Mudd, became wealthy teenagers through ownership of resource-rich lands. In 1895, Anna Beaver Hallam (1887-1971) and other relatives in the Quapaw tribe were each awarded 200 acres located in Ottawa county, OK. She earned a monthly royalty income of $50,000 in 1905 from her zinc and lead mines, and became a millionaire. In 1933, Hanna Anderson, a 26 year old Creek Indian in Tulsa, OK, owned oil funds amounting to over $1 million dollars.

Lulu M. Heffner (1874 – 1954) of the Cherokee tribe in Nowata, Oklahoma, was an exceptionally successful entrepreneur in the oil and gas business. She was known as the “largest lady property owner” in the region, and noted for her “keen… discernment and judgement.” As an oil operator who drilled twenty eight productive oil wells herself, she managed movie theaters along with other flourishing businesses. In 1918, she expanded to Brownwood Texas, where she leased 10,000 acres of land. She said, “Next to being a Cherokee Indian, I am proudest of being a business woman of Oklahoma.”

Beauty and the Marketplace

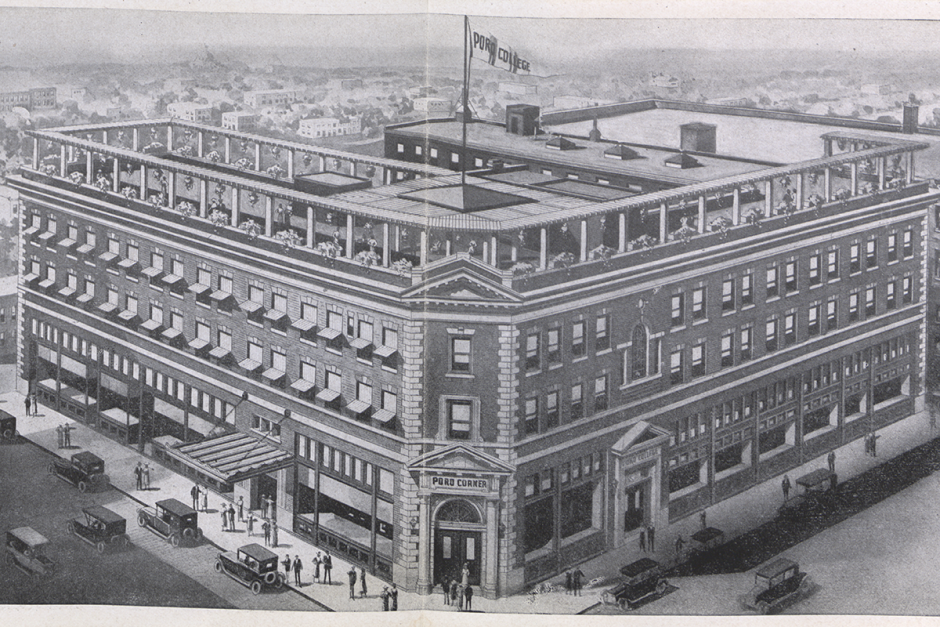

Annie Minerva Turnbo Malone (1869-1957), a pioneer in the lucrative African-American beauty industry, was born in Metropolis, IL, and left orphaned as a child. At the height of her fortune in the 1920s, she was recorded as the richest person in the state of Missouri, with a net worth of $14 million. In 1923, her tax bill amounted to over $34,000, at a time when the average tax payment was $96. Malone produced an innovative line of hair products and cosmetics for black customers. In addition, she franchised her methods and trained aspiring cosmetologists in an international network. Her greatest business assets were a keen sense of marketing and organizational abilities. Annie M. Malone realized the value of branding, and closely monitored her firm’s intellectual property. She registered the Poro trademark in 1906, and obtained a design patent for a decorative tape to seal boxes of her products in May 16, 1922. Several lawsuits were filed against rivals whose trademarks were regarding as infringing, including even the use of the syllable “po.”

Malone founded Poro Beauty College in 1902 in St. Louis, and later erected an elaborate complex spanning an entire city block, with some 250 employees. Branch schools were established throughout the United States, the West Indies, and South America, drawing on an army of 75,000 part-time agents. “The agent’s course of instruction is thorough, but is often supplemented by additional work taken in person at the College. As an inducement to keep abreast of the latest practices, review courses with ten days’ free board and lodging are offered each agent once a year, and those who take the courses are shown every courtesy during their stay at the college.” She moved her headquarters to Chicago in 1938, acquiring a tract of land extending over the entire east side of South Park. She was devoted to causes ranging from disadvantaged orphans to full scholarships for black students in every land grant university in the country.

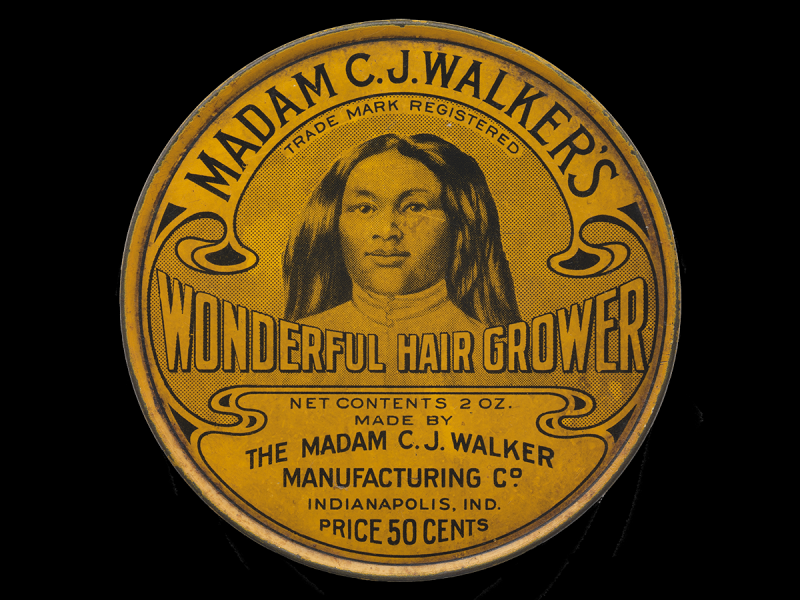

Sarah Breedlove Walker (1867-1919), who adopted the name of Madame C. J. Walker, was initially one of Annie Malone’s Poro beauty agents. Walker emulated her mentor’s products and business model, but denied any connection, instead crediting divine inspiration in the form of a dream. She started a similar line of beauty products for black customers, and her own training school for beauticians, with an accompanying Madame C. J. Walker textbook of “beauty culture.” Her entrepreneurial career spanned a little over a decade, from 1906 to her death in 1919. At that time, her factory employed 65 workers, and there were around 20,000 agents in the U.S. and overseas.

Walker was actually not a millionaire, though she left a substantial estate of $500,000 and her personal effects were later auctioned for $58,000. The common claim that she was a patented inventor is also inaccurate. Walker did not hold any patents herself, but her company purchased the rights to several inventions (including two by Marjorie Joyner, who later became a vice-president of the firm).

Sarah Walker, a five-foot-tall former washerwoman, was acutely conscious of the power of a curated image, or (as one reporter diplomatically put it) “a respect for printer’s ink.” She toured about giving well-attended lectures, and fed colourful inflated details to the press to ensure that she was constantly the topic of news articles. Her success in this regard is visible today in her numerous awards and coverage whenever the topic of minority businesswomen is discussed.

Sarah Walker was a remarkable woman and entrepreneur, with impressive achievements that are worth celebrating. However, the insistence that she was the first financially-successful businesswoman is not just factually false, it also rewrites history by painting out the thousands of minority women who prospered through their own initiative and efforts, from the founding of the Republic. The greatest value would be attached to research efforts that go beyond the usual anecdotes about the usual suspects, to uncover more about these invisible women.

Cherokee Woman, Oklahoma, 1930

Cherokee Woman, Oklahoma, 1930