The tsunami of new inventions and innovations in nineteenth century America transformed the world to an extent that arguably remains unmatched today. Consider the impact of the telegraph, which could send messages in a matter of seconds, relative to weeks or even months by “pony express.”

Even among the New England states known for their “Yankee ingenuity,” Maine inventors surpassed their peers. The very first patent granted after the patent system was reformed in 1836, Patent No. 1, was to Maine senator John Ruggles. Prominent patentees included the first American to be knighted by Queen Victoria, Sir Hiram S. Maxim, his brother Hudson Maxim, and his son Hiram Percy Maxim (widely denounced for subsidizing criminals by inventing the silencer for pistols). Bowdoin graduates made key contributions from steam engines to electricity. Maine even celebrates December 21 as Chester Greenwood Day, to honour the inventor of ear muffs (and the invaluable doughnut hook).

Maine women were as creative as their male counterparts, and their ideas and entrepreneurship led to extraordinary business success in metropolitan markets. Just 45 women appear among the over 600 American inventors in the Hall of Fame, but two of them were born in antebellum Maine: Margaret Knight and Helen Blanchard.

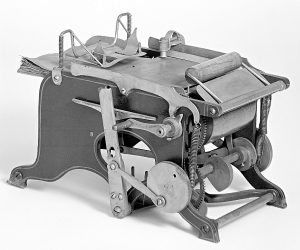

Satchel Bottoms and Bag Machines: A professional inventor like Hiram Maxim, Margaret Eloise Knight was similarly honoured by the Queen, and inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Knight was born in York in 1838 and, like many children of the time, received minimal formal education before she started working at an early age. The majority of great inventors were “insiders” whose discoveries were related to bottlenecks they observed in the course of their occupations. As an apprentice, Knight learned a range of skills in these different jobs, and later was hired as a machine operator at the Columbia Paper Bag Company in Springfield, Massachusetts. She soon realized the value of finding a way to mechanically produce paper bags with square bottoms, now familiar to any shopper in the supermarket.

Many others were attempting to devise an improvement on paper bag machines, including the talented Charles F. Annan, who patented numerous related inventions. In 1871, Knight filed a patent interference claim against Annan, to prove priority to the specific design she had invented. Popular histories of women inventors have ever since vilified Annan as a typical unscrupulous male (“dishonest fraud”) out to steal the credit from a defenceless female. They fail to understand that it is quite common for patent interferences to occur when several inventors claim protection for the same ideas. The Eastern Paper Bag Company was founded to exploit Knight’s invention, and Annan himself later sold the rights to some of his patents to the firm – an unlikely occurrence if he had indeed nefariously tried to steal Knight’s ideas.

Many others were attempting to devise an improvement on paper bag machines, including the talented Charles F. Annan, who patented numerous related inventions. In 1871, Knight filed a patent interference claim against Annan, to prove priority to the specific design she had invented. Popular histories of women inventors have ever since vilified Annan as a typical unscrupulous male (“dishonest fraud”) out to steal the credit from a defenceless female. They fail to understand that it is quite common for patent interferences to occur when several inventors claim protection for the same ideas. The Eastern Paper Bag Company was founded to exploit Knight’s invention, and Annan himself later sold the rights to some of his patents to the firm – an unlikely occurrence if he had indeed nefariously tried to steal Knight’s ideas.

The interference report, however, provides interesting details about the trial and error nature of the four years of work that led up to the perfected invention of 1871:“Miss Knight, on the contrary, has introduced voluminous testimony, and has stated fully the history of her invention from its first inception down to the present time. From her own statement, which is abundantly corroborated by other witnesses, it appears that she conceived the idea of the invention in February, 1867, and in the same month made a rude sketch, which is preserved and made an exhibit in the case, of those portions of the machine which are involved in the present controversy. In the following month she made a rude paper model, intended to embody her ideas, and also constructed a guide – finger and a plate knife folder, with which she experimented privately ; which subsequently, viz, in February, 1868, she attached to one of the old paper – bag machines in the shop in Springfield, Massachusetts, where she was employed; and with which, as she testifies, she succeeded in making square – bottom bags. In the latter month, also, she commenced a wooden model, which she completed in July, 1868, and upon which she says that she made “thousands of bags.””

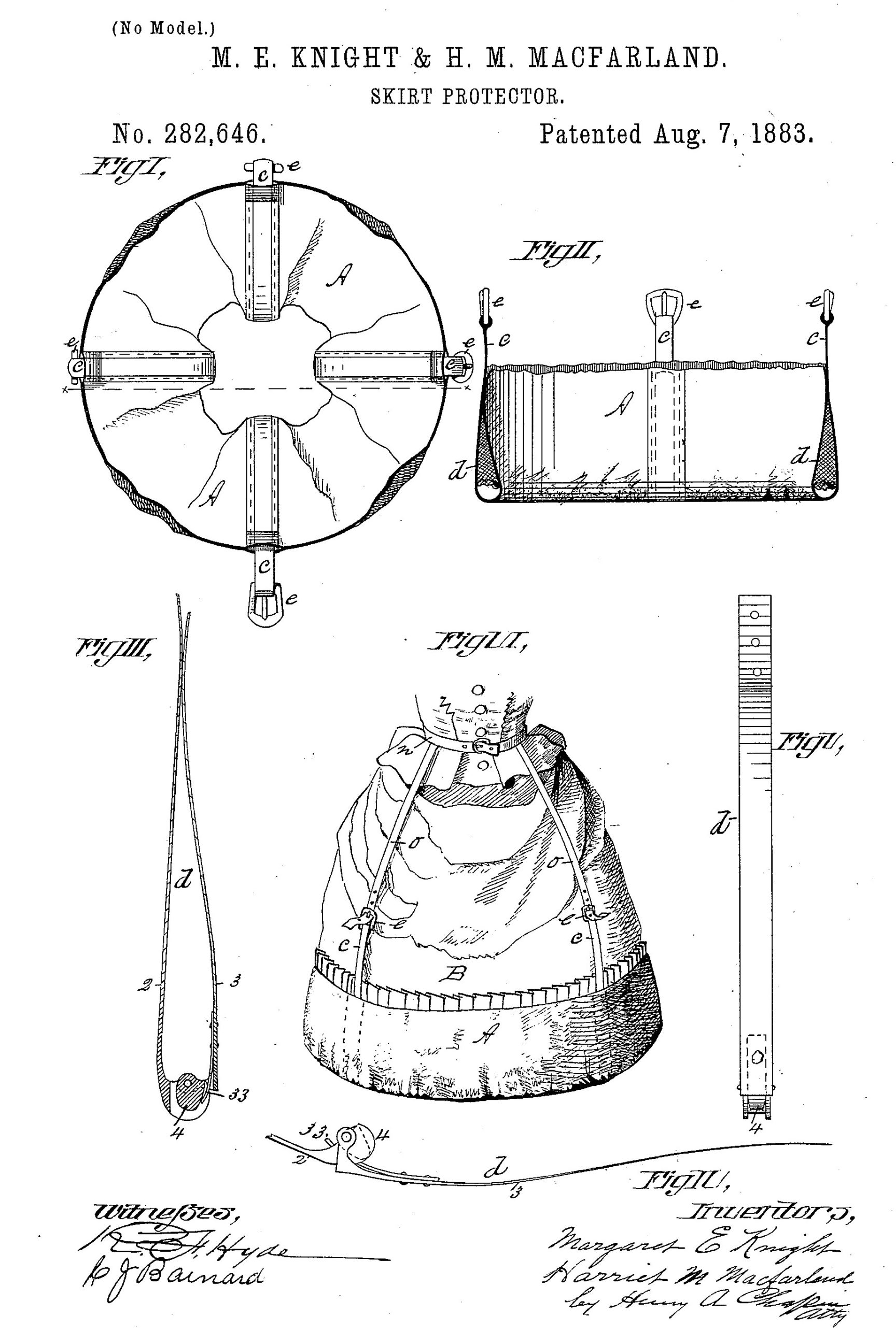

Margaret Knight obtained patents on a wide array of inventions, including machines to cut shoe-soles. She collaborated with another woman inventor to patent a dress shield “which will afford perfect protection for the skirts against rain, snow, and dirt,” which no doubt proved invaluable to the female population in Maine. Throughout her productive life she never stopped trying to improve on emerging technologies. By 1910 she had turned her attention to automobiles, obtaining Patent No. 1,015,761 for a Resilient Wheel, and also filed patents for improved motors and car engines. On her death in 1914, The Horseless Age, an automobile trade journal, noted the loss of “the “Woman Edison,” who first attracted attention in the automobile world early in 1912 by her introduction of a sleeve Valve motor at the Boston show.”

Margaret Knight obtained patents on a wide array of inventions, including machines to cut shoe-soles. She collaborated with another woman inventor to patent a dress shield “which will afford perfect protection for the skirts against rain, snow, and dirt,” which no doubt proved invaluable to the female population in Maine. Throughout her productive life she never stopped trying to improve on emerging technologies. By 1910 she had turned her attention to automobiles, obtaining Patent No. 1,015,761 for a Resilient Wheel, and also filed patents for improved motors and car engines. On her death in 1914, The Horseless Age, an automobile trade journal, noted the loss of “the “Woman Edison,” who first attracted attention in the automobile world early in 1912 by her introduction of a sleeve Valve motor at the Boston show.”

Zigzag Path to Success

Helen Augusta Blanchard was born in Portland, Maine in 1840 to a wealthy merchant family. Like most great inventors, she migrated to larger commercial markets in Boston and Philadelphia. She sold and licensed her patent rights, and built her own factory to manufacture sewing machines. According to the Milwaukee Sentinel of 7 Mar. 1888: “She owns large estates, a manufactory, and many patent rights. Her fortune, royalties and income, without venturing statements accurate enough to be impertinent, may be described in the fluent language of the… sensational reporter, as “beyond the wildest dreams of avarice.” She earned it all herself. She had no assistance from anyone, and hired money at 25 per cent. to pay her first patent office fees.” Sources such as these are somewhat suspect, since the patent fee was just $35, but there is no question that Helen Blanchard became very wealthy from her own inventive efforts.

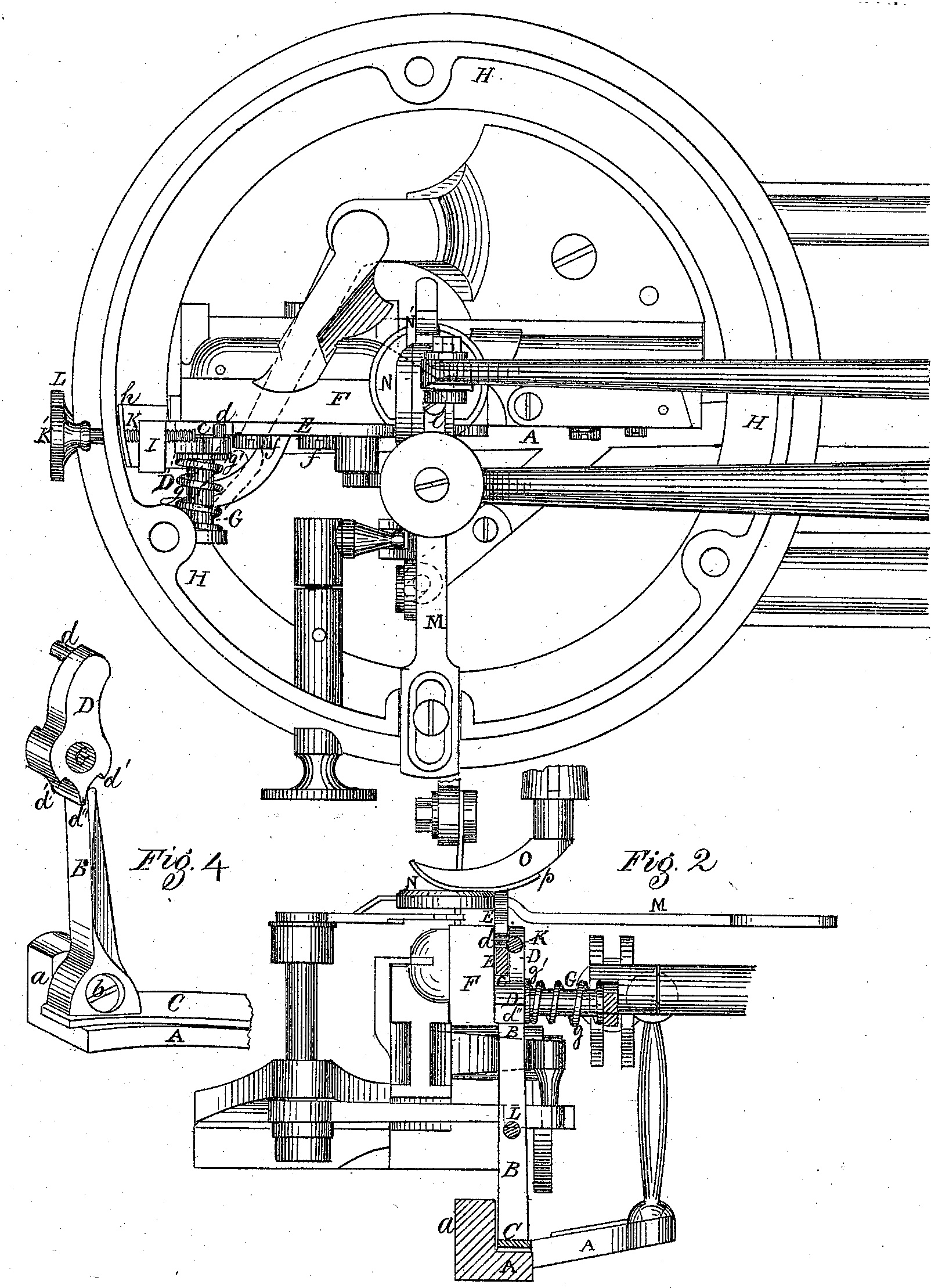

Blanchard specialized in sewing machine inventions, that produced stiches like the zig-zag and buttonhole. Firms making apparel valued the overseam machine because prior handwork could now be neatly trimmed mechanically for the first time, and it cost just 10 cents per dozen to make items which could then be sold for 25 cents. Wilcox & Gibbs, a major sewing machine company, paid royalties for the right to the Blanchard patent. The Blanchard Overseam Company of Philadelphia, which was founded in 1876, also produced products such as hat-bands, and acquired the rights to related patents. In 1881, the fierce competition between Blanchard and major hat-band corporations like Stetson was resolved by cross-licensing and pooling their patent rights. Blanchard was deemed a “woman of the century,” and her discoveries were “ranked among the most remarkable mechanical contrivances of the age.”

Blanchard specialized in sewing machine inventions, that produced stiches like the zig-zag and buttonhole. Firms making apparel valued the overseam machine because prior handwork could now be neatly trimmed mechanically for the first time, and it cost just 10 cents per dozen to make items which could then be sold for 25 cents. Wilcox & Gibbs, a major sewing machine company, paid royalties for the right to the Blanchard patent. The Blanchard Overseam Company of Philadelphia, which was founded in 1876, also produced products such as hat-bands, and acquired the rights to related patents. In 1881, the fierce competition between Blanchard and major hat-band corporations like Stetson was resolved by cross-licensing and pooling their patent rights. Blanchard was deemed a “woman of the century,” and her discoveries were “ranked among the most remarkable mechanical contrivances of the age.”

No Feminine Trifles Admitted: Advocates of women’s rights have always been eager to publicize women inventors like Margaret Knight and Helen Blanchard, who patented technically advanced industrial machines. The organizers of the Women’s Pavilion for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 preferred “to make no note of the inventions of women unless it is something quite distinguished and brilliant. We must not call attention to anything that would cause us to lose ground.” They were disappointed to find feminine inventions were predominantly new types of household products, kitchen tools and apparel, and by trying to suppress these “undistinguished” contributions, ironically contributed to the notion that women were not inventive.

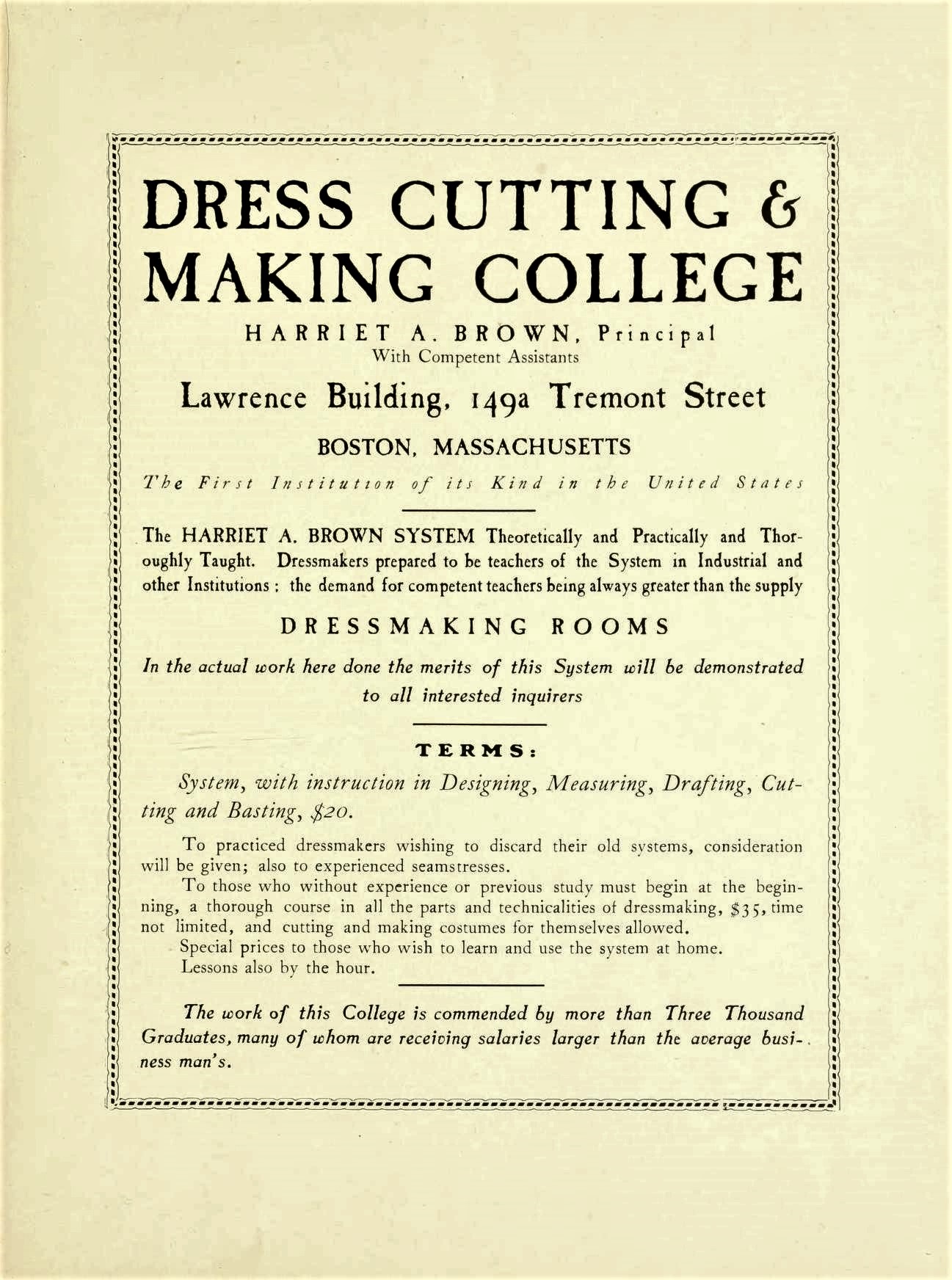

Maine inventors Harriet A. Brown (pictured here) and Julia Penley both directed their ingenuity to the market for dress charts and dress-making. Wealthy and middle-class women ordered garments that were individually tailored for them by modistes and seamstresses. Dress charts, which provided simple patterns that could be followed and cut out at home by even unskilled sewers, created a democratization of affordable clothing for women and children.

Maine inventors Harriet A. Brown (pictured here) and Julia Penley both directed their ingenuity to the market for dress charts and dress-making. Wealthy and middle-class women ordered garments that were individually tailored for them by modistes and seamstresses. Dress charts, which provided simple patterns that could be followed and cut out at home by even unskilled sewers, created a democratization of affordable clothing for women and children.

Julia Penley received her first patent for dress charts while she was living in Bangor, and she moved to Portland to open her own dressmaking school. Her 1889 patent noted that “My invention consists in an improved chart for cutting out dress-patterns. It is adapted to enable any one of ordinary intelligence to prepare from simple measurements a pattern for a woman or child…”

As a signal of the value of her idea, she also obtained patent protection and marketed her inventions in Canada. She received royalties from schools who were teaching her innovative methods to dressmakers and seamstresses. For instance, an advertisement in Le Trifluvien, Quebec in 1894 noted that the head of Mme Hamel’s Academy of Dress-cutting had received a diploma in Julia Penley’s methods that qualified Hamel to instruct others.

In 1884, Penley managed an establishment at 48 Winter Street in Boston, and earned a diploma at the Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. The jury reported that: “This exhibitor claims that the “Penley Patent French Tailor System is the latest and most popular scientific tailor system in existence. Superior to all other systems, as it is so simple a child can use it, yet so accurate and so swift to draft that experienced dressmakers once seeing it will use no other. It saves time, anxiety, and material. This system is easily learned in a few hours… a dress waist can be drafted from it in three minutes.” The Judges consider it an “excellent system, simple and easily learned.”

Similarly, Harriet A. Brown, who was born in Augusta, Maine, patented her influential method of dressmaking which was widely adopted. She was adept at advertising and self-advertisement, claiming to have opened the first dressmaking school in the world, the Boston College of Dress Cutting and Dress Making. The school was “commended by more than Three Thousand Graduates, many of whom are receiving salaries larger than the average business man’s.” The booklet on her work notes that her system was much copied, and “It has been a business necessity for me to protect my patents, and in some instances to enforce injunctions on rival establishments.” As a means of marketing, she pursued awards at all the major industrial fairs, including the 1893 world’s fair. She modestly noted, “That my system obtained a great triumph at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, must be by all conceded. To competent judges was committed the duty of designating the best dressmaking system in the world; and this award was given to my system.”

Similarly, Harriet A. Brown, who was born in Augusta, Maine, patented her influential method of dressmaking which was widely adopted. She was adept at advertising and self-advertisement, claiming to have opened the first dressmaking school in the world, the Boston College of Dress Cutting and Dress Making. The school was “commended by more than Three Thousand Graduates, many of whom are receiving salaries larger than the average business man’s.” The booklet on her work notes that her system was much copied, and “It has been a business necessity for me to protect my patents, and in some instances to enforce injunctions on rival establishments.” As a means of marketing, she pursued awards at all the major industrial fairs, including the 1893 world’s fair. She modestly noted, “That my system obtained a great triumph at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, must be by all conceded. To competent judges was committed the duty of designating the best dressmaking system in the world; and this award was given to my system.”

Beyond the Halls of Fame: What makes any inventor or invention “great”? Technical skills, celebrity, influential connections, and luck all play a role. Hedy Lamarr, the glamorous film star, co-inventor of frequency-hopping to evade blocking of radio guidance signals, is a fixture in popular stories about innovative women. However, the value of any invention is a function of its technical features and of its commercial worth in the market. A machine of great complexity that is never used has little value to society; conversely, a wire simply twisted into a safety pin or paper clip has significant economic and social value. Women had a comparative advantage in detecting the needs of the household, and they productively directed their attention to supposedly minor inventions that drastically improved the wellbeing of other women and their families. By any measure, the dress charts of Harriet Brown or Julia Penley created far more benefits for far more people than Hedy Lamarr’s patented idea.

Further reading: B. Zorina Khan, “`Not for Ornament’: Patenting Activity by Women Inventors,”