The word apprentice conjures up visions of sorcerers and medieval guilds (as well as my great-grandmother, a goldsmith who learned her trade through a family apprenticeship). Actually, today most doctoral students labour as apprentices to their thesis supervisor, before advancing as a fully-fledged member of the guild of economists. And apprenticeships seem destined to become as effective a means of human-capital acquisition for the future, as they have been for millenia.

White Collar, Blue Collar, New Collar

My research into the first and second industrial revolutions in Britain, France, and America investigated the role of human capital in enterprise and innovation. European policies were vested in a top-down technocratic approach that highlighted the central role of the state, elites, scarce factor inputs, and “upper tail knowledge.” Some economists argue that the industrial revolution occurred because of costly investments in higher education, scientists, and engineers. They conclude that “the presence of knowledge elites drives growth in the industrial era” and even, bizarrely, that “worker skills are not relevant to growth.”

Unlike Europe, American policies linked together universal access to basic education, and the capacity to make valuable inventions. It is not a coincidence that the Pennsylvania Frame of Government in the 1600s highlighted the need to “erect and order all public schools, and encourage and reward the authors of useful sciences and laudable inventions.”

The most productive great inventors like Thomas Edison acquired skills and knowledge from apprenticeships and learning by doing. Many important inventions were discovered when an employee detected bottlenecks in production processes, and came up with ways to resolve them. Engineering or college degrees were not required for economically important technological discoveries. I’m not a fan of Thomas Jefferson but, as he pointed out, there is a vast difference between technical value and economic value: “a smaller [invention], applicable to our daily concerns, is infinitely more valuable than the greatest… For these interest the few alone, the former the many.”

Apprenticeships proved to be cheap, flexible and effective routes to train or “retool” innovative workers, including skilled and unskilled immigrants. Women inventors, in particular, benefited from apprenticeships within the family. American leadership in the nineteenth century was not created by Ivy League graduates and “knowledge elites;” rather, a primary factor was the humble apprenticeship system and its role in promoting diversity of skills and ideas.

That was Then, This is Now?

No doubt you will shrug and say that history is history, and apprenticeships are not relevant to this brave new world of the 21st century. However, the evidence suggests otherwise; in fact, apprenticeships might even be MORE relevant today than in prior eras.

First of all, note that the founders of some of the most disruptive enterprises today did NOT graduate from college. Entrepreneurs who never went beyond high school or dropped out of undergraduate colleges include Bill Gates and Paul Allen (Microsoft), Larry Ellison (Oracle), Steve Jobs (Apple), Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook), David Karp (Tumblr), Peter Cashmore (Mashable), Michael Lazaridis (Research in Motion), Jack Dorsey and Evan Williams (Twitter), Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker (Napster), Michael Dell (Dell Computers), Travis Kalanick (Uber), Jan Koum (WhatsApp), and Daniel Elk (Spotify).

According to Marc Benioff, the CEO of Salesforce, “our companies are some of the best universities in the world,” and he lobbies for “a moonshot goal to create five million apprenticeships in the next five years.” Another tech billionaire (best unnamed) offers 30 Fellowships of $100,000 every year — to induce young people to drop out of college.

IBM has established a “New Collar” (perhaps more appropriately, no collar?) Apprenticeship Programme. Participants acquire technical skills while getting paid, in the form of “an intensive work-based development program, with comprehensive learning, focused hands-on training, and mentorship.” Credentials include digital badges earned from qualified activities like online courses or hackathons.

Escaping the Third Degree

It might seem peculiar that a liberal arts college professor with three degrees from three countries should be promoting non-college education. But we economists are always easy to understand (just put it down to costs and benefits, or demand and supply). According to the Current Population Survey, in 2020, two thirds of recent high school graduates ages 16 to 24 were enrolled in colleges and universities. At present, student loan debt amounts to over $1.75 trillion and is expected to exceed $2 trillion by 2024. At the same time, fully a third of graduates who received a bachelor’s degree in 2020 were unemployed. The median holder of an undergraduate degree does not glean positive returns until after 15 years of employment.

By contrast, apprentices are paid to learn and highly employable. The average starting salary after finishing an apprenticeship programme is $72,000, and well over 90 percent of apprentices are offered positions in their internship placement. Forbes, which prides itself on reporting on “the world’s richest movers and shakers,” ranked two-year trade schools, concluding that “a top-tier trade school is a better option for lots of high school grads than … a middling four-year program.”

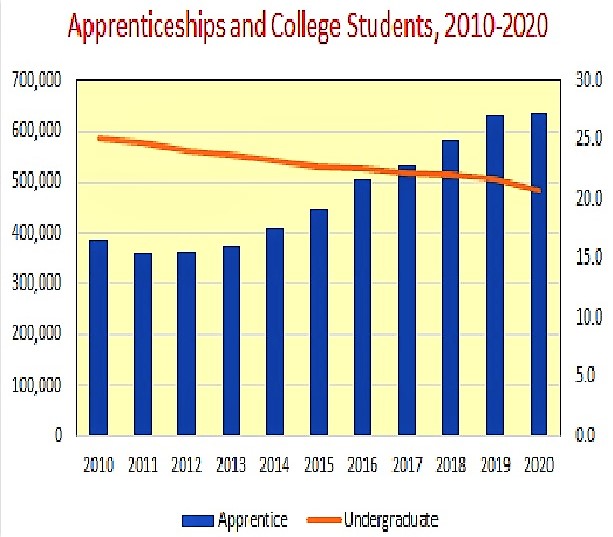

As the graph shows, although the number of conventional college students is vastly higher, interest in apprenticeships has been increasing. A 2021 survey found that a majority of high school students are now interested in pursuing trade-related prospects, which typically have a high probability (or even a guarantee) of future employment, while reducing financial indebtedness. You can always read Marguerite Yourcenar or appraise German Expressionism and the works of Olivier Messiaen in your spare time (as I do.)

The Once and Future Human Capital Model?

Europe has increasingly demonstrated how apprenticeships offer a model for the future. An OECD survey of vocational education proclaimed that, for both students and social welfare, apprenticeships are more relevant than conventional education, because the training is jointly designed with employers and other stakeholders.

Switzerland in particular stands out as a leader in global competitiveness, in large part because of its pervasive and popular apprenticeship system. Nearly two-thirds of Swiss teenagers ages 16 to 18 combine school and work through the country’s vocational and education training (VET) programme. Each student is partnered with a firm that invests heavily in apprentices’ training. The VET model provides students with paid learning on the job, combined with learning in the classroom using a curriculum that is aligned with the demands of the employer. Fully 70% of Swiss high school graduates enter apprenticeships, in fields that include high-tech areas like computing, software and health technology. Indeed, currently only around 25% of high school students go on to study at universities.

As such, in Switzerland apprenticeship is the predominant form of education and training, so it is unsurprising that in the World Skills competition, Switzerland has won numerous medals. Moreover, many prominent Swiss entrepreneurs and leaders were part of the apprenticeship system, including CEOs of corporations and financial institutions. Government officials and leaders have benefited as well, like the Economics Minister who participated in an agricultural apprenticeship. Rather than foreclosing on choices and locking participants into a narrow path, an apprenticeship offers an option with more decision routes than alternative models.

Don’t Know Much About History

When I was invited to a conference at the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, I thought that my presentation on the benefits of apprenticeship would be greeted with eye-rolling. Instead, I was surprised to find that another session was devoted to discussing how this model was being promoted as a novel policy for the future in the United States.

According to CareerWise Colorado, “youth apprenticeship is a new concept in the United States,” so the state government is motivating this form of human capital acquisition by pointing to the Swiss model. Perhaps they might also turn to such home-grown institutions as the “Williamson Free School of Mechanical Trades,” that was founded in 1888 for just that purpose. Or the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers, which advertises positions in “hacking apprenticeships.” Or openings for Systems Support Apprentices in Research Triangle Park, NC.

The U.S. Labour Department has committed $113 million to “strengthen, modernize, expand and diversify” the Registered Apprenticeship Program, as a means to reduce inequality and promote social justice. The “women in apprenticeship fact-sheet” optimistically celebrates the finding that “the number of female apprentices has increased 218% from 2014 to 2019” – which is true enough, but women still comprise just 11 percent of total apprentices. In short, American prosperity in past centuries was built on apprenticeships, but the current statistics show that there is still a long way to go before we progress back to the future.