Thomas Edison is one of the most legendary inventors in American history. His portfolio of some 1093 U.S. patents include improvements in telegraphy, the stock ticker, storage batteries, the phonograph, films – and, of course, incandescent light bulbs. Edison himself regarded the electrical illumination inventions as his most significant technological discoveries.

Like many “great inventors,” Edison did not receive any formal schooling, and his trial-and-error methods were based on thousands of experiments. Edison’s investors were concerned that his competitors were highly-educated engineers and formally-trained scientists, who would outpace him in the race to commercialize these innovations. For example, Elihu Thomson had taught physics and chemistry and his inventions were based on a thorough understanding of the underlying scientific principles.

Like many “great inventors,” Edison did not receive any formal schooling, and his trial-and-error methods were based on thousands of experiments. Edison’s investors were concerned that his competitors were highly-educated engineers and formally-trained scientists, who would outpace him in the race to commercialize these innovations. For example, Elihu Thomson had taught physics and chemistry and his inventions were based on a thorough understanding of the underlying scientific principles.

Edison remained a productive inventor for most of his life, partly because his Menlo Park and West Orange laboratories attracted brilliant young scientists, machinists and engineers. Prominent among these were two Bowdoin graduates from the class of 1875, Francis Upton and Charles Clarke. It is unlikely that Edison would have dominated the field of electrical illumination without Upton’s contributions, in particular. Isaac Adams Jr., another Bowdoin alumnus, invented an incandescent bulb long before Edison, and would be on the opposing side of the table in the struggle to control the market for lighting.

Bowdoin Culture: Francis Robbins Upton

After the Civil War, as my research shows, college-educated individuals were increasingly characteristic of great inventors, and by the start of the twentieth century formal education was typical of technologically significant discoveries, especially in the profitable electrical sector. According to the Wall Street Journal, March 14, 1918, “the electro-chemical industry of the United States has been so developed as now to make it certain that it is about to establish a new era in American industry.” Like the modern dot.com boom, inventions and investments in electrical discoveries generated large fortunes, and readily attracted flows of venture capital for speculative research and development.

Edison’s investors were aware of these patterns, and advised the hiring of new talent with advanced technical qualifications. In response, Francis Robbins Upton, who graduated from Bowdoin in 1875 with a B.S. degree, was recruited at Menlo Park in November, 1878. He would work with Edison for some 25 years, and was responsible for the rationalization of the lab’s approach.

Upton, a mathematician and physicist, was the first postgraduate at Princeton. The following year he studied the mathematics of electrodynamics at the University of Berlin, under the supervision of the notable Hermann von Helmholtz. A member of the Peucinian Society, Upton was a “brilliant young man” with a keen and versatile mind, who kept up to date on publications in German and French, and was a virtuoso piano player. He raised the tone and intellectual level at Menlo Park to the extent that his nickname was “Culture.” Upton was married in Brunswick, ME in 1879, and his son Francis Upton Jr. also graduated from Bowdoin, in the class of 1908.

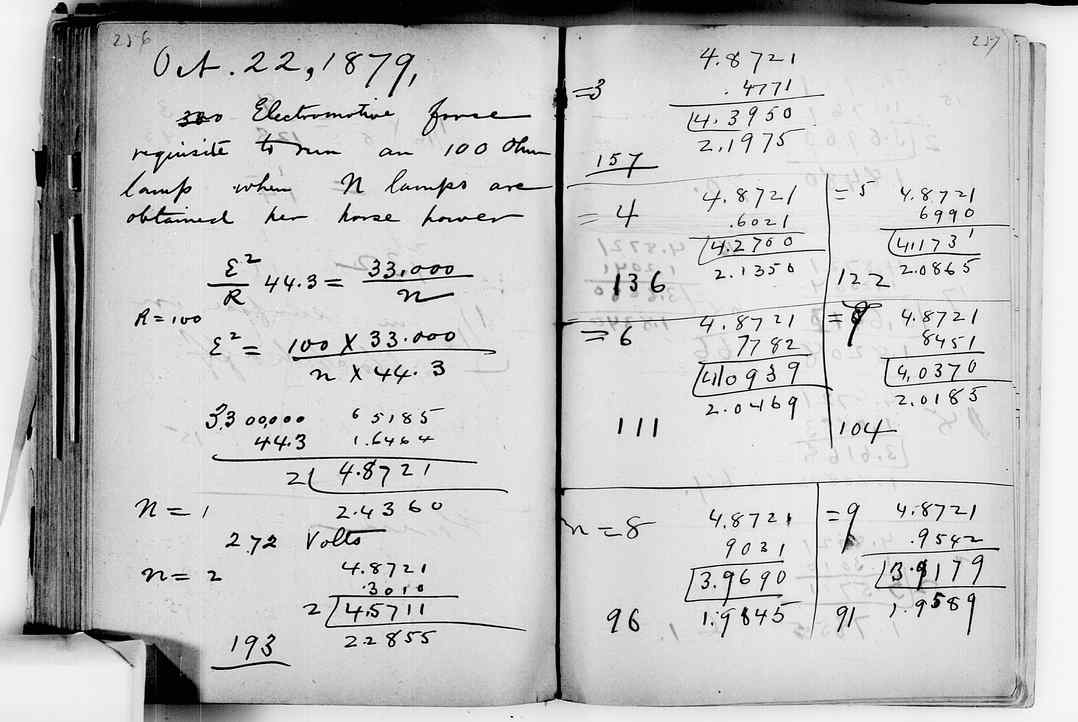

At Menlo Park, Upton’s contributions to the discovery of a viable light bulb, electrical dynamos and meters, and related applications, were second only to those of Edison. He was able to determine the underlying theoretical principles of technical problems, which allowed more general solutions and extensions than practical experiments permitted. (See his notebook at the left.) At one point, Edison poked fun at his methods by asking him to determine the cubical content of a pear-shaped container. Upton set to work by manipulating complex integral and differential equations — Edison instead suggested the simpler expedient of filling the glass and measuring the weight.

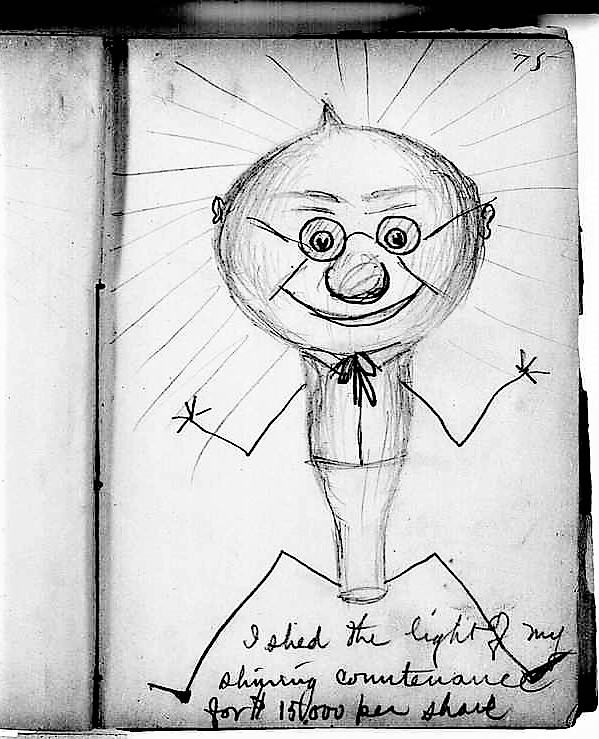

Their collaborations in theoretical research and empirical experiments led to a perfected light bulb in 1879, and Upton’s house became the first in the world to be illuminated by electricity. (This light bulb cartoon of his indicates he evidently was more talented in math than art.) Upton became a partner in the Edison Lamp works, the 1880 venture to commercialize their discovery, and received a 5 percent share of the profits from the electric lighting patents. He continued to manage the firm’s operations until 1894, two years after the merger with Thomson to form the General Electric Corporation. According to one biographer, “Francis Robbins Upton … is spoken of wherever the “wizard’s” achievements are known…. In fact, Mr. Upton’s interests have been for years synonymous with the name of Edison.” He was elected as the president of the “Edison Pioneers,” a group of the early researchers involved in the quest for commercially-successful lighting.

Apart from his work with Edison, Francis Upton is also known for his co-invention of the first successful electrical fire alarm, patented in 1890. This portable device emitted “an audible local alarm when the temperature at a certain point rises above the predetermined limit… to provide means for giving a local fire-alarm in buildings which are not wired and connected.”

Charles Lorenzo Clarke and the Insomnia Squad

Charles Clarke graduated in civil engineering at Bowdoin College in the same year as his “chum” Francis Upton, and he was also trained in Europe. At the end of 1879, Upton wrote to him from Menlo Park: “I think I have a chance here for you. Between you and me, Mr. Edison has found a most elegant light which is going to be largely used; and to put it up properly will require a large number of young men with theoretical training. The finest problems in steam engineering are involved and the highest state of electrical science.”

Clarke described his interview with Edison: “Upton took me back to the office, hunted up Edison, and bringing him in said: ‘This is the friend I have told you about. He is a better mathematician than I am.’ With his genial little smile, so well known, and his quick direct manner, Edison jerked out: ‘All right — glad to have you come — give you twelve dollars a week.’ I expressed my satisfaction. A pleasant nod and a handshake closed the transaction — and Edison was gone — back to his problems in the laboratory.”

Clarke read up on the elements of electrical engineering (about which he was completely ignorant), and formally joined Menlo Park in February 1, 1880. His first experience was not a happy one, since he short-circuited the electrical light in the lab. His mistake “was a good joke to the others, especially to Edison. I forthwith learned from him what constitutes short circuiting, why it occurs, and how it can be avoided. Yes, in a few minutes I learned a lot about the multiple-arc lighting system.” However, Clarke applied himself assiduously, and quickly became adept in the field: “I was constantly observant of all that was going on about me, working and studying overtime, as the ambitious young should ever do if they expect to move onward and upward.” The long work hours earned the close-knit group the self-imposed title of the “Insomnia Squad.”

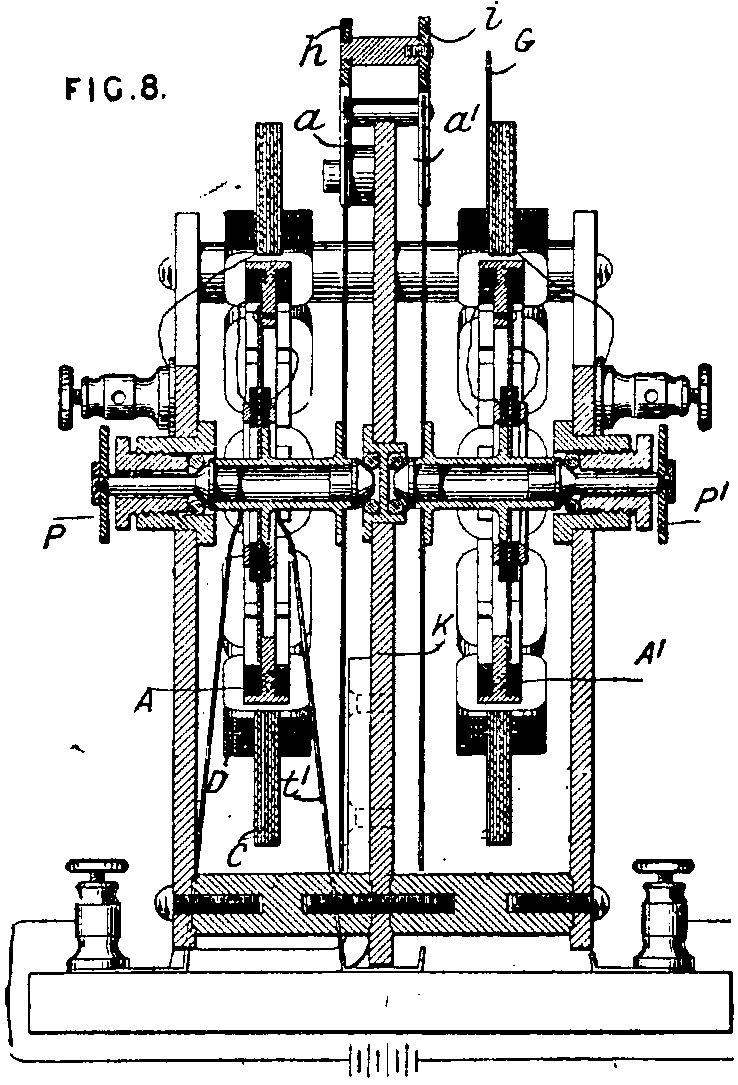

The mathematical calculations that Clarke produced and his multifaceted contributions to the distribution of lighting and electricity soon became vital. For instance, he was able to calculate the dimensions and cost of conductors to enable the functioning of a central station system. Edison also depended on Clarke’s work for the design and development of efficient dynamos with greater electrical capacity, and an effective electrical distribution system. Two years later, Edison personally appointed Clarke as the chief engineer of the parent Edison Electric Light Company in New York City. Clarke’s living quarters were in the same office building, because Edison wanted him to be on hand at all times. Clarke was happy to accept such tradeoffs, since he felt they were devoting their efforts to the Common Good, or “utilities of such value that they continue to this day profoundly to affect the ways of civilization to the betterment of mankind.”

Who invented the light bulb? Anyone who studies technology is (or should be) aware that this question is nonsensical. Technological innovation is an evolutionary process, that typically consists of a multitude of incremental improvements. Samuel Morse did not invent the first or even the best telegraph, even if his name is most frequently attached to this invention. In the same manner, Edison invented a light bulb, he did not invent the light bulb.

For some, the first inventor of a viable light bulb was actually Isaac Adams Jr., Bowdoin class of 1858. Adams’ father, Isaac Sr., was a “great inventor,” and he made a fortune from his printing press technology and manufacturing enterprises. Like many of his peers, he had come from a disadvantaged background, working in the mills from the age of nine without any formal education, and he wanted his son to have all the benefits that he had not possessed. He envisioned Isaac Jr. as a genteel medical doctor, and sent him to Bowdoin and Harvard, and finally to study with the leading authorities in Paris.

Isaac Adams Jr. was indeed certified as a physician, but ironically soon abandoned this career to follow his father’s path as an eminent inventor. Isaac Jr. became interested in the area of electricity and chemistry. In particular, he is noted for his valuable patented inventions in nickel-electroplating, and (like his father) was entrepreneurial in extracting financial returns by founding his own corporations, including the United Nickel Plating Company.

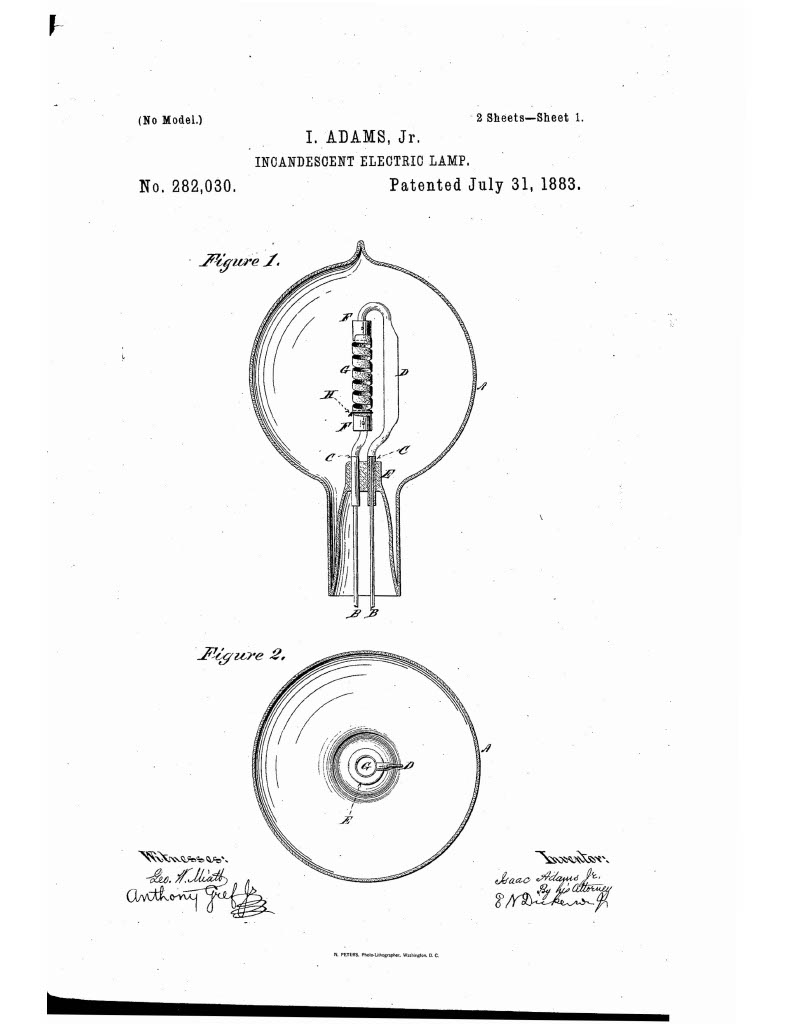

While he was in Paris, Adams encountered gas-filled glass tubes, which illuminated when subjected to electrical currents. He learned how to make variations on these Geissler tubes, which he marketed commercially to companies in Boston. In 1865, in the course of experimentation with the tubes, he created an incandescent light bulb using a carbon filament, fourteen years before Edison did so. Adams did not seek to commercialize or pursue these prospects until he applied for his own patent on incandescent electric lamps on April 4, 1882 (Patent No. 282,030, dated July 31, 1883).

Patent litigation rates were highest in the electricity and communications industry, and Edison outstripped all his litigious competitors by engaging in some 60 reported lawsuits. The Edison Electric Light Company filed a case against the United States Electric Lighting Company, involving the Edison filament lamp patent. Isaac Adams was asked to testify by the defendants, who hoped that his account would invalidate Edison’s patent for the light bulb. Adams, however, candidly conceded that he had realized his invention was useful for serving as a lamp, but unlike Edison, “I was not proposing to get up a system of lighting, not at all.”

Isaac Adams Jr. had undoubtedly conceived of a viable light bulb years before Edison, but he failed to identify its most profitable commercial use, and he never even bothered to file for a patent on his discovery. Edison attributed much of his lifelong productivity to perseverance rather than inspiration, and further noted that “genius is hard work, stick-to-it-iveness, and common sense.” He was quick to seek federal protection for his ideas through patent applications, and brainstormed with the members of the Insomnia Squad to pursue the most effective means of marketing and commercialization. As a result of the hard work of himself, Francis Upton and his Menlo Park associates, Edison won the lawsuit, and the resulting designation of “the inventor of the light bulb.” Isaac Adams would have to be satisfied with the label of the “father of electroplating.”