Fans of the history of technology can quickly name a dozen significant British inventors, but very few would be able to identify any women with noteworthy discoveries. In its 200-year run, the London Times published fewer than six articles on the subject. In fact, many earlier references to “the woman inventor” in English newspapers were actually about Americans, who were regarded as especially ingenious by observers in other countries.

Want is the Mistress of Invention

Any accounting of British female inventive activity must start with Amy Everard, the first woman inventor on record to obtain a patent, no. 104, in 1637. She claimed to possess “the mystery, skill, and invention” of making essential tinctures from saffron, roses, and other flowers. The widowed inventor was allowed to pay the hefty patent fees on an installment plan, but even so must have been quite wealthy or else very confident in the commercial prospects for her potions.

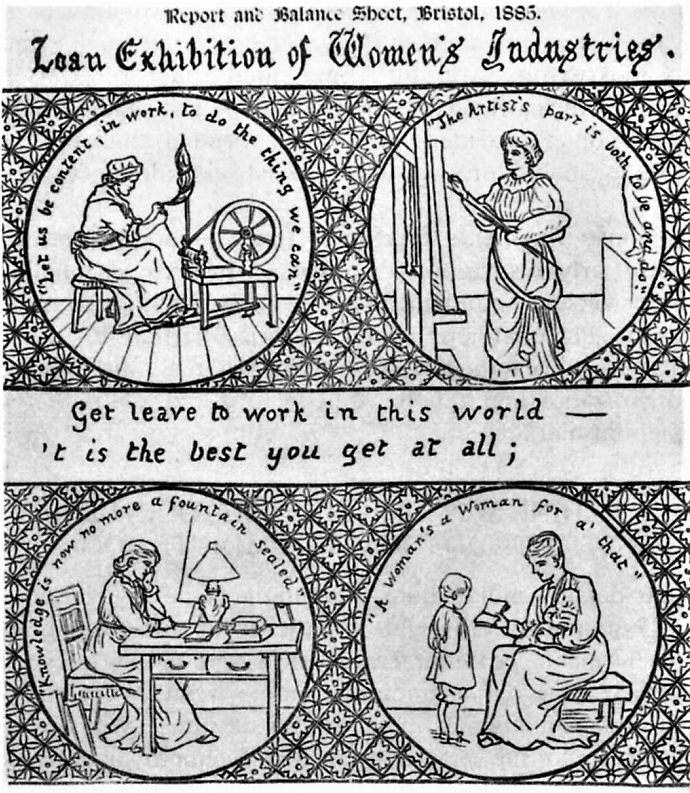

To Susannah Centlivre, author of The Busy Body (1709), “Want [is] the mistress of invention,” and this is clearly true of the numerous women who tried to improve their lives by designing more comfortable clothing. The patent records are rife with new and improved corsets, cycling togs that didn’t affront modesty, and other forms of innovative apparel, leading the British Patent Office to start publicizing statistics for this category towards the end of the nineteenth century.

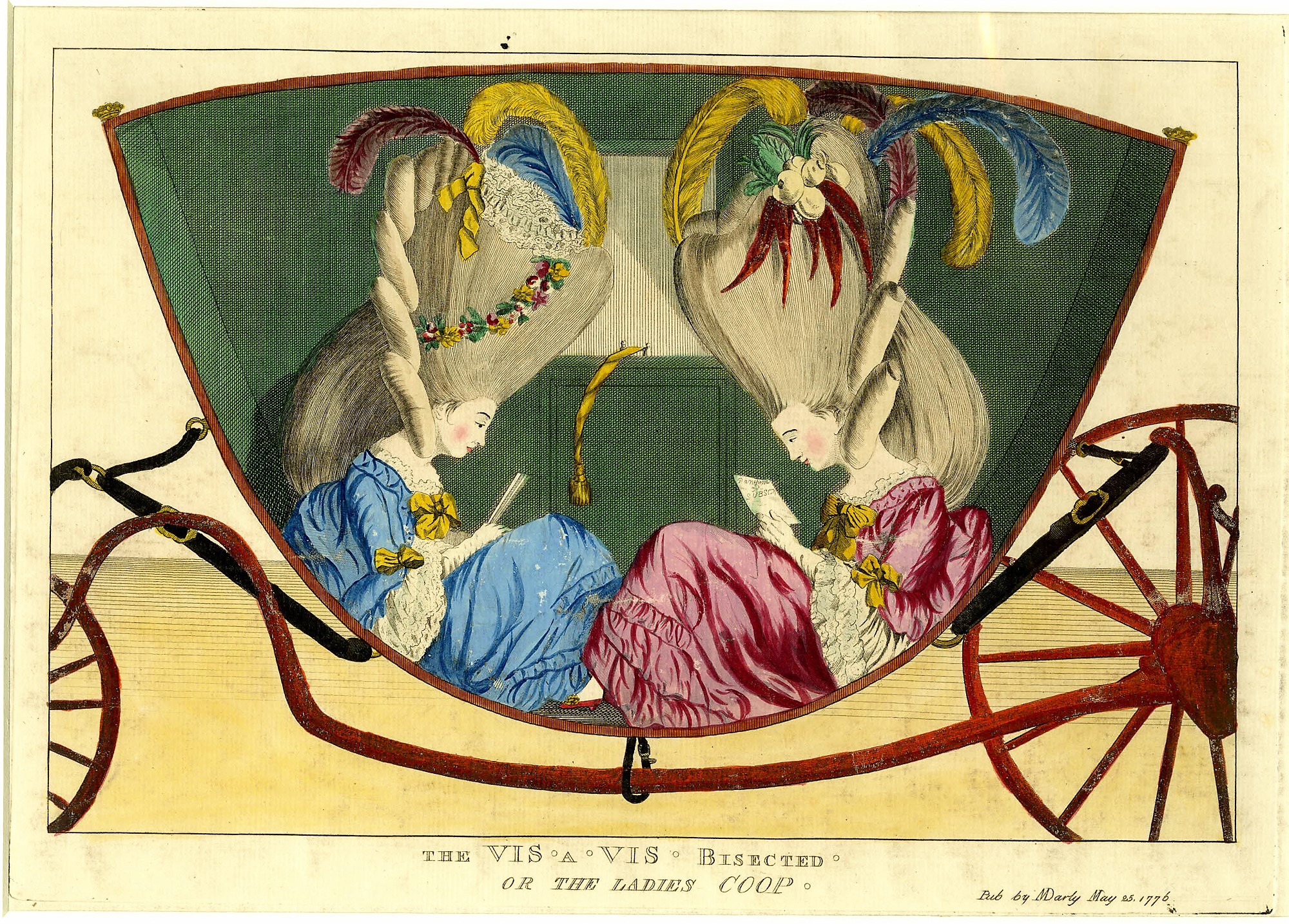

Part of the impetus for such efforts can be illustrated through the experience of Jane Vanef , of Westminster. She produced hoops for skirts, which at the time were so voluminous and unwieldy that a good deal of quasi-engineering skill was required to construct them. Fashionable garments could balloon out to a diameter of five feet or more, which created logistical problems in negotiating confined areas. Vanef’s 1737 patent was to protect her discovery of “A way of compressing the hoops of skirts to allow for entry and exit into carriages, churches and other enclosed spaces.” Spoiler alert: think collapsible, hinges, and whalebones.

The Busy Body Sarah Guppy (1770-1852) was the wife of a wealthy Bristol merchant, and she obtained four patents, the first filed at the age of 41 and the last when she was 74. Much has been made of her 1811 suspension bridge invention, including unfounded charges that famous male engineers stole/were gifted/purloined her idea; however, there is no evidence that her bridge design was ever commercialized or embedded in any other construction. Indeed, the uncharitable might point out that any claim of originality was merely due to a lack of knowledge about the plethora of such inventions already in existence. But, speaking of beds, Ms. Guppy did invent a novel fourposter with attached exercise equipment to ease the sluggish into a busy day.

The energetic Mrs. Guppy, like many other women inventors, turned her attention in 1812 to ensuring greater efficiency in the kitchen. Her compendium urn allowed the user to simultaneously brew tea or coffee, boil eggs, and keep toast and foods warm. The patent document included the following modest endnote (look up apophasis): “OBSERVATIONS BY THE PATENTEE. The superior utility of these urns is so very evident, that it is quite unnecessary to say anything in their favour—they speak for themselves; and those persons who have already used them speak highly of their convenience: and as the additional expense is trifling, it is presumed no person will deprive themselves of the accommodation on account of their cost.”

Endnote by the uncharitable: “Observations:– If a trifling luxury (the boiling of eggs) at the breakfast table of the opulent be worthy of a separate and expensive apparatus, surely Mrs. Guppy’s invention, which is intended and perhaps calculated to render this luxury less expensive, … will entitle herself to the thanks, and her invention to the adoption, of the sons of fortune!”

Engineering the Art of Invention

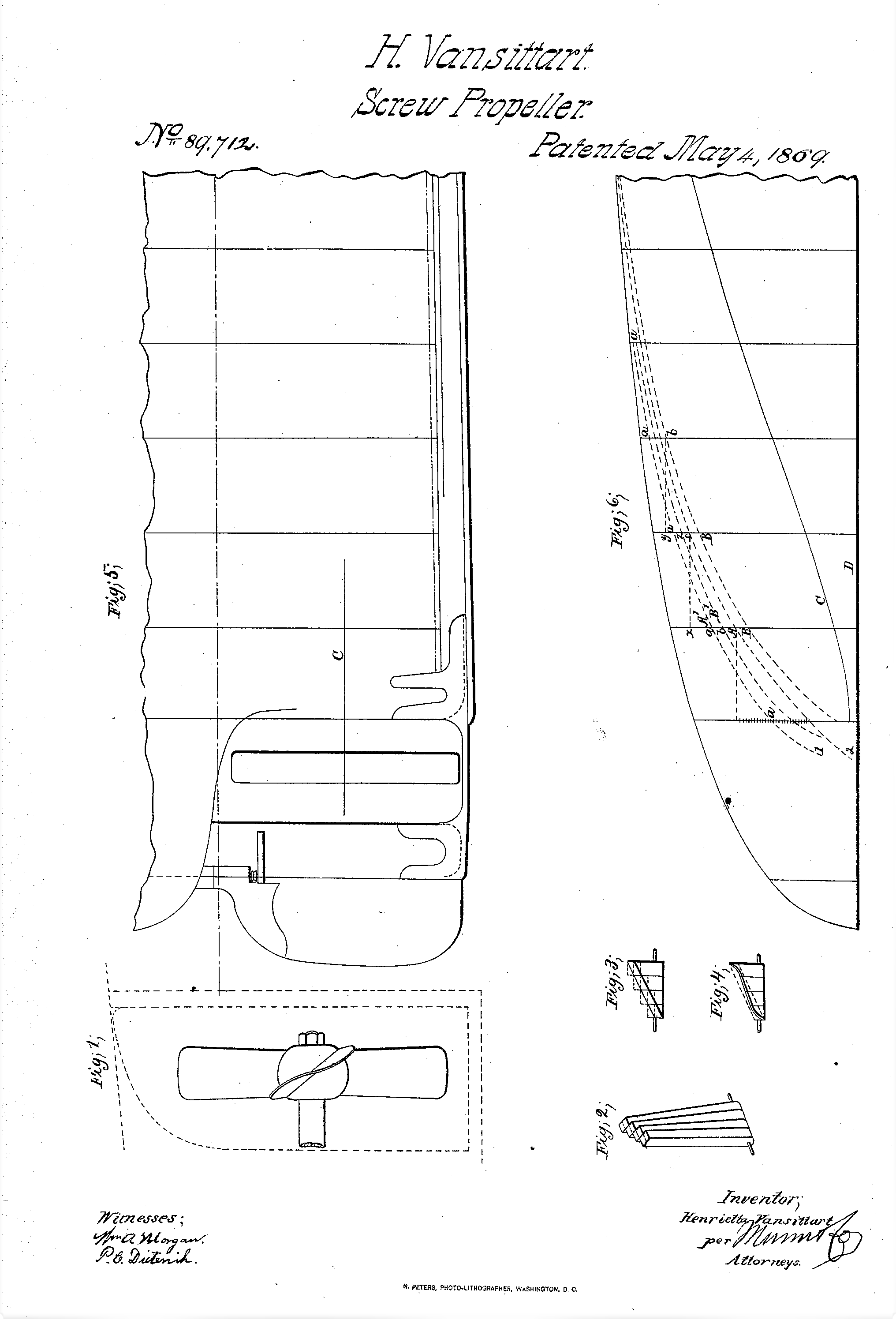

Is a single improvement sufficient to justify billing as an eminent inventor? This was the case with Henrietta Vansittart (1833-1883,) who is often featured as a prominent inventor (and an engineer, in the Dictionary of National Biography), but described herself as a “mechanical artist.” Her father, James Lowe, had patented and worked on a ship’s propeller for several decades, and after his death she continued improving on his invention through numerous practical experiments. Her version ended up “combining several of his peculiarities, together with some novel points.” The Lowe-Vansittart propeller was noted for its smooth operation without any vibrations, and efficiency in consumption of fuel while maintaining speed and steering ability. In 1868 she was granted Patent No. 2877 , and the propeller was used in warships and mercantile vessels “with good results.” In 1869, Vansittart applied for provisional patent protection for another screw propeller improvement, but never completed the application.

Successful inventors benefited from a support network, and this was especially true of women. When asked what factors were most important in encouraging the development of female engineers, Verena Holmes noted that “the most desirable assets are a father in an influential position in the profession and sufficient means to tide over training and periods of unemployment.” Perhaps one of the reasons why Henrietta Vansittart stands out today is that she was indefatigable in promoting her father’s work and her own, including exhibits at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, and the bestowing of models and artifacts to prominent museums.

Hertha’s Arc

Hertha Ayrton (1854–1923) has been described as “Britain’s foremost women inventor,” and “the most distinguished woman scientist” in the country at that time. Ayrton came from a poor background but, in the absence of a rich father, was fortunate in attracting the attention and financial support of well-positioned patrons, which allowed her to study mathematics at Girton (Third Class Honours), and electrical engineering through evening classes. Like Vansittart, she benefited from association with a family member – she married her instructor, the eminent William Ayrton, a pioneering inventor in electricity. (Hertha Ayrton added, on notifying her mother about the proposal, “He is also going to let me go on with my electrical work, and of course he can help me in it in every way.”) She published influential papers in The Electrician and was the first female member of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Her nomination for membership at the Royal Society was rejected because married women were deemed ineligible, but she was awarded a prestigious prize.

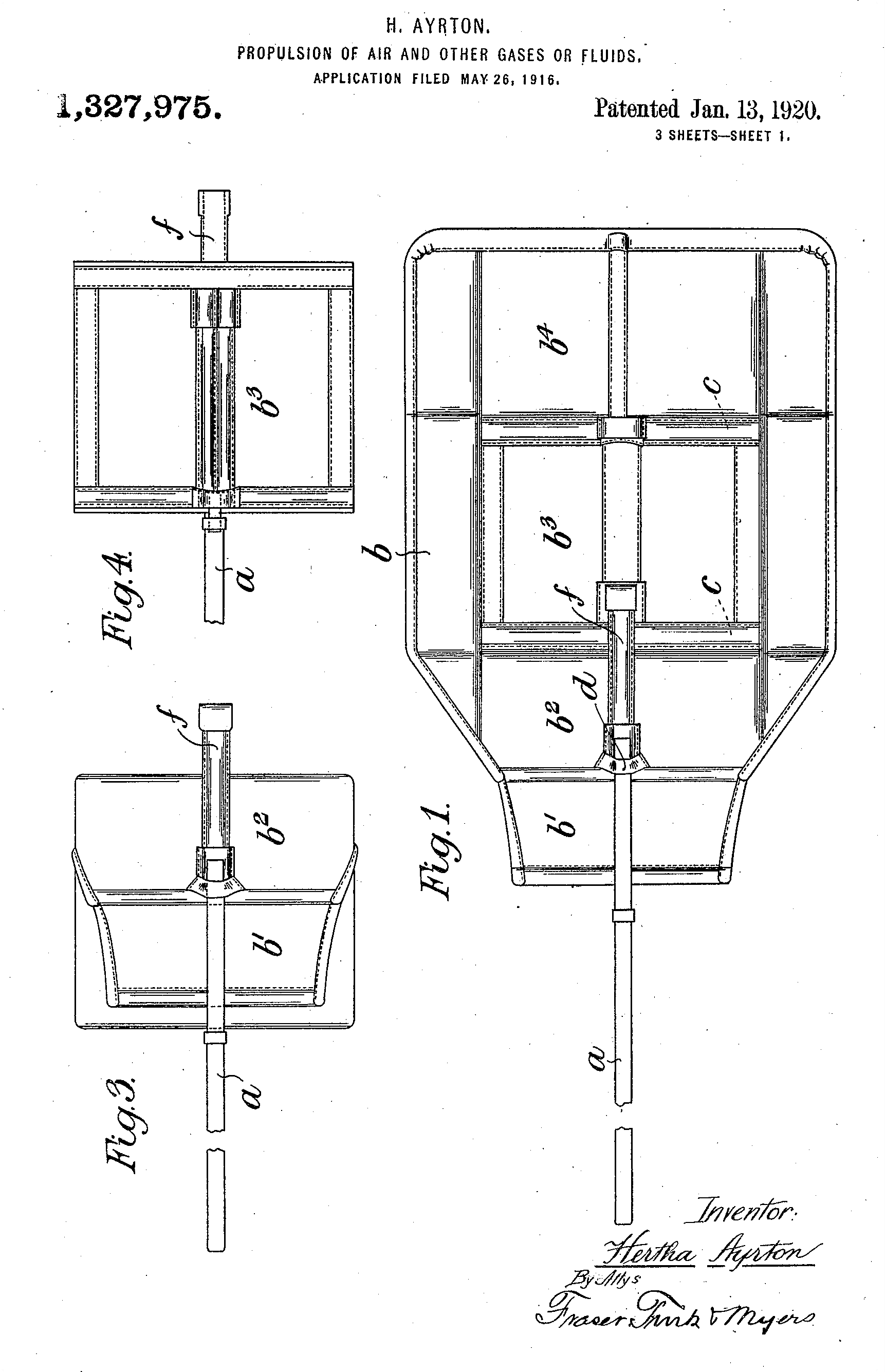

Suffragist backers financed Hertha Ayrton’s 1884 British and U.S. patents for an elegant mathematical line divider. She was credited with saving numerous soldier’s lives during World War I when she invented a simple hand-held fan to dispel poison gas in the trenches. Towards the end of the war, about 100,000 fans were dispatched to the front, owing to her own lobbying efforts. She later applied similar principles in several inventions for the propulsion of noxious gases in industrial settings. Her most significant technological contributions owed to her electricity research, including anti-aircraft searchlights and arc lamp technology. Patents for these discoveries were filed internationally, including France, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria (which has led to double counting of her inventions by many scholars, and misleading claims that she filed “26 British patents.”) By the 1920s, her occupation was listed on these documents as “scientist,” and Ayrton was certainly a notable scientist; but was she indeed “Britain’s foremost woman inventor”?

The Votes Are In

My own vote for the foremost British woman inventor in the early twentieth century would go to Verena Winifred Holmes (1889-1964). It’s remarkably difficult to find documented information, or even photographs, for her career — even Sarah Guppy gave more interviews to the popular press. Holmes was brought up in an ordinary middle-class home, and succeeded through her own hard work and disciplined mind. Like many women who were drafted into work during the First World War, Holmes developed technical skills on the job. She worked as an apprentice at a propeller company, and studied at night classes, finally succeeding in attending engineering college. During the Second World War she worked for the Admiralty on such complex mechanisms as valves for torpedoes.

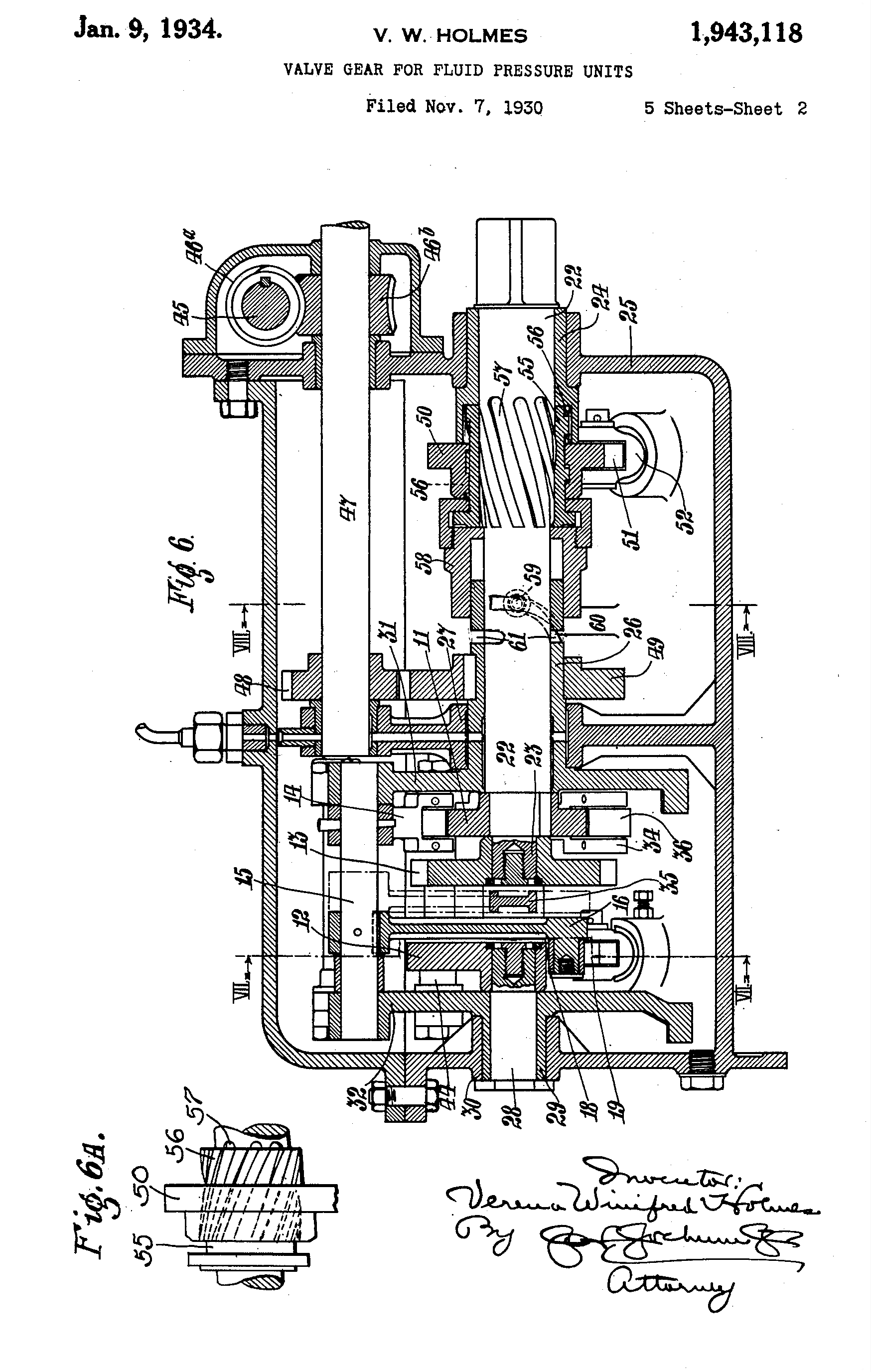

Holmes developed a wide range of well-cited innovative marine and locomotive engines, diesel engines, and internal combustion engines. Between 1921 and 1958, she successfully applied for at least fifteen British patents, along with foreign patents from the United States, France and Canada. Their subject matter spanned a diversity of fields and technologies, including medical instruments, valves for internal combustion engines, diving suits, safety paper guillotines, scissors and stencil machines, and a speaker to amplify sounds. Many of these inventions were successfully commercialized, and after 1946 some of these devices were manufactured at her own engineering firm, which employed only women.

Verena Holmes was the first female member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (the link is to its membership page). An ardent supporter of women’s technical education, she was also a founding member of the Women’s Engineering Society (her 1931 Presidential speech on locomotive valve gears, appears on pages 119-128 of the society’s journal.)

A Summing Up

Women inventors have always encountered numerous obstacles in their attempts to commercialize their creativity. British laws such as exceptionally high patent fees and weak married women’s property rights inhibited their inventive activity. At the Patent Office, the first female patent examiner was not appointed until Miss F. M. Shepherd, a graduate of the University of London, filled the position in 1930. Women who circumvented such institutional barriers tended to come from rather privileged backgrounds, or to have influential connections – patent rosters include a cotillion of aristocratic ladies, countesses, baronesses, and even a duchess or two. However, biographies such as Verena Holmes’s demonstrate that individual initiative could be just as potent as wealth, patronage, and self-promotion in generating notable technological innovation and social change.