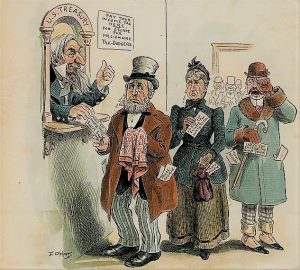

In 1887, the Los Angeles Times declared, “This is an age not only of millionaires, but of millionairesses as well.” Wealthy women “worth their weight in gold” had existed from the beginning of American history, but the scope for their commercial and financial activities increased exponentially during the industrial revolution and surging economic growth dating from the 1840s. Systematic evidence of lifetime wealth is almost entirely absent for women, leading to the impression that women’s property and assets were only passively acquired through marriage and inheritance. Even extremely wealthy women entrepreneurs have often remained invisible to scholarship and to financial history.

One of these invisible millionaires, Polly Clapp Lewis (1780-1865) was widowed in 1824, and lived with her eldest son and his family on a palatial estate in Framingham, Massachusetts. In the 1850s, she held more than 11,000 shares in Maine corporations, amounting to some $750 million relative to income today. She was the majority stockholder in the Springvale Manufacturing Company, a risky textile firm that had been spun off from the troubled and heavily-indebted Sanford Company around 1842, and her holdings amounted to 25 percent of the total capitalization of Springvale corporation. These assets are entirely missing from the federal population censuses, which have blank entries for her wealth, as is often the case for women.

Women Millionaires in the Gilded Age

A century ago, Forbes surveyed the top 30 richest industrialists, including household names like John D. Rockefeller, Henry Frick, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Ford. The three women on the list, Mrs. E. H. Harriman, Mrs. Russell Sage, and Mrs. Lawrence Lewis, were there by virtue of their marriage to rich men. The richest woman of the Gilded Age, Mary Williamson Harriman, inherited $69 million on the death of her husband in 1909.

This list was hardly representative, however, and more comprehensive estimates of the American elite class invariably missed an extensive array of female entrepreneurs. In 1891, tax filings revealed 40 women millionaires in New York City alone. The records for 1917 included 432 women, or 6.5 percent of the total 6664 millionaires in the United States. Such data failed to include women like Mary S. Holladay, president of the Williamsville, Greenville & St Louis Railroad, who “sold her stock for a cold million in cash” in 1910. In 1927, the reported 153 women millionaires in Chicago owned average wealth of $3 million. Several had increased the value of their estates through active management. The richest woman in Chicago, Edith Rockefeller McCormick, was a daughter of John D. Rockefeller, and ex-wife of the wealthy Harold F. McCormick, who had increased her holdings with shrewd real estate investments.

One of the self-made women millionaires was the entrepreneurial Bertha Baur, who took over the controlling interest in the Liquid Carbonic company at her husband’s death. Liquid carbonic is a pressurized and liquified gas, that was used for the production of soft drinks, fire extinguishers, and a range of other industrial products. As vice-president, she helped turned the failing company into a growing and profitable business. In 1926, she sold her shares for $7 million when the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

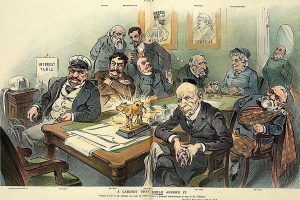

Hetty Green (1824-1916), one the most well-known financiers of the century, was present on the Forbes 1918 list by proxy, as Ed H.R. Green (1868–1936) acquired most of his fortune from his mother. Hetty Green was one of the twelve entries in the 1941 book, “Men of Wealth,” and her husband Edward was known primarily as the “husband of the world’s richest woman.” She had started out with an inheritance of around $12 million, but through her brilliant business initiative her estate was ultimately valued at $95 million when she died. She was a metaphor for the self-made woman, and captivated the attention not just of Americans, but also the rest of the world. Over a thousand newspaper articles continually parsed topics such as What Mrs Green says, Hetty Green not ill, An economical millionaire, Princess of whales, Tax dodging with Hetty Green, Poor Hetty Green, and even Hetty Green’s dog has a bank account. Many did not find it necessary to add her whole name, simply referring to “Hetty” in the headline.

“A cabinet that could afford it,” including Rockefeller as Sec. of Treasury, and Hetty Green

Hetty Green Redux

Hetty Green was far from unique, however.

The Washington Post wrote in Oct 1909 that “Perhaps no woman has received more fame for her business ability than Mrs Weightman Walker … Mrs Walker as a financier rivaled Mrs. Green.” Anne Weightman Walker (1844 – 1932) was one of the richest women in the world, who was continually mobbed by “camera fiends.” Her first husband, Robert J. C. Walker left her $10 million and she also inherited extensive assets from her father in 1904. She actively managed her business enterprises, driving to the office at 8 a.m. each day, and keeping close tabs on all transactions and decisions. The NYT noted that, at age 60, she was worth $50 million and in charge of a great chemical plant, commanding “a small army of employees.” They hastened to add that, despite her business acumen, she was still “a womanly woman.”

Ada Sawyer Garrett (1856–1938) was one of the wealthiest women in Chicago, and her “life story would put to shame the tales of Hetty Green.” Ada Sawyer had been a Chicago belle and wealthy heiress, pursued by many. After the death of her husband Timothy Mauro Garrett (1855-1903), she withdrew from social life, and devoted herself entirely to saving and investing her money. She was so successful that she ended up with a portfolio valued in excess of $6 million, acquired through real estate and loan transactions in Chicago. According to a flurry of newspaper reports in 1927, she was leading a miser’s existence, living in penury in a cheap and inconvenient room next to the noisy elevated railway, and subsisting on sandwiches and tea. At the same time, she was engaging in selfless acts of charity, including funding a mission for 150 homeless individuals. When she died in 1938, she bequeathed several million dollars to the University of Chicago and various charitable institutions, including homes for the poor, orphans and the disadvantaged.

Mrs. Henrietta M. King (1832-1895) in 1890 was “probably the richest woman in the United States, not excepting Mrs. Hetty Green.” A cattle baroness, her estate was valued at over $5 million, and extended over 1.5 million acres south of Corpus Christi, Texas, an area as large as the state of Delaware. The King ranch was stocked with 100,000 head of cattle and horses, and employed over 1000 cowboys and hands, including her son-in-law. “Mrs. King herself, however, never loosens the rein she holds over her affairs and she is the real manager of the entire property, nothing of an importance being done without consulting with her… Without the King support no man dare aspire for office in that section of the world.” An adjacent property was owned by another female millionaire rancher, Mrs. Rogers.

The Hetty Green Gold Standard

Hetty Green was the standard by which ever other successful businesswoman was measured. The following titles were bestowed by newspaper articles:

Maryland’s Hetty Green: Mrs. Evelyn S. Tome, president of two national banks in Maryland, the Cecil National Bank, and the Elkton National Bank.

Maine’s Hetty Green: Lucy Farnsworth was an eccentric self-made millionaire, who endowed the famous Farnsworth Art Museum in her will.

Bronx Hetty Green: Sarah Josephine Bent was an active investor in the stock market, and an associate of J P Morgan. When she died, her estate exceeded $3 million, but she left nothing for her second husband, 24 years younger than she was.

Alaska’s Hetty Green: Inuit Princess Tom was the first Native American woman to become a self-made millionaire. “The trading instinct was as strong in her as ever it was in Jay Gould or in Russell Sage,” the Washington Post noted in 1897.

Hetty Green of Los Angeles: Mrs Sophia Meyran was the owner of “great business interests” in Pittsburgh and Los Angeles. Like Hetty Green, she lived very frugally, but was generous in distributing funds to various charities.

Michigan Hetty Green: The financial acumen of Mrs. Catherine Briggs increased her husband’s bequest tenfold.

Cuba’s Hetty Green: Rosa Abreu owned extensive sugar and coffee plantations, as well as other enterprises.

A Japanese Hetty Green: Mrs. Kiyo Minejima created a fortune of over $12 million. She owned extensive real estate in Tokyo, and was the founder of a bank and trust company, all of which she managed “with an iron hand.”

Japan’s Hetty Green: Kin Seno, the founder and president of a successful bank.

Another Japanese Hetty Green, Japanese Rockefeller and even a “Japanese Morgan”: YONE SUZUKI, the Kobe multi-millionaire, was deemed one of the most successful business women in the world, dominating both finance and industry. The Wall Street Journal reported in 1923 that Suzuki and Co. had incorporated two establishments in San Francisco, with $40 million in capital, each headed by Yone Suzuki. The global Suzuki business empire spanned many continents and included ownership of 115 ocean liners, along with vast holdings of cotton mills, silk firms, canneries, breweries, sugar refineries, and coal manufacturing enterprises.

It would perhaps be more accurate to refer to Hetty Green as the American Yone Suzuki.